Reading the press release for Eli Ruhala and Tad Greenwald’s partner show, “Ephemera(lity),”a stark déjà vu set in. The purple descriptions of “transitory moments” and “human experience” seemed to be plucked straight from my freshman year lit major mind. They’re the academic’s version of magazine collage ransom notes: hodge-podge and reused. They’re that emphatic “society”tossed into every pseudo social justice warrior’s vocabulary. Thankfully, Ruhala and Greenwald, though fresh off the boat of academia, exceed expectations with work that curtails the pull of time by redirecting focus onto empirically candid narratives.

Both educated at the Maryland Institute College of Art, Ruhala and Greenwald are new artists in the gallery scene. With only a few prior exhibitions, their recent opening was met with a particularly buzzing anticipation and interest in what they had in store. Ruhala’s drywall painting expresses a knack for the experimental while Greenwald’s watercolor technique speaks of expert training. I can’t help but feel the artists were cheated out of solo exhibitions though, as both bodies of work express equally finished and unique concepts. Redeeming this, an optimistic appreciation of the mundane and forgettable draws a clearer connection between both artist’s work.

In first viewing Ruhala’s work, I felt notably lost. Whether I lost track of time digesting his work or trapped in the memorial space of his stories, my mind bowed and ached in rough waters. Ruhala’s sedimentary compositions expose the layers of age and memory in context to their narratives. Like counting rings on a tree for age, I scope the highly textured surface for answers.

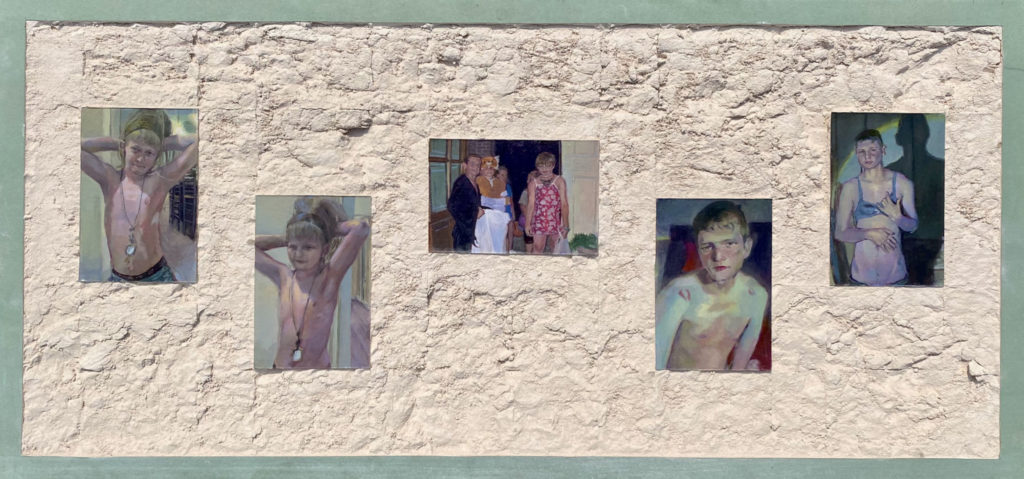

Take for instance “Fragments (Cross-Dress),”where Ruhala depicts five chronological self-portraits in an excavated collage. From left to right, versions of the artist pose in wigs, dresses and bralettes. The autobiographical confrontation of his masculinity breaks with the notion that queer children always “grow into their own” or the counterargument’s less convincing, “they are born queer.” Instead, the specific, active snapshots rise from their shallow grave speaking not what they “were/are”but what they “did/do.”

“[To] make my feelings into an actual piece and put it out there…that’s the part for me that’s creating the home,” Ruhala said.

Like the materials he uses, Ruhala takes ideas of gender identity and expounds them into the most active of terms. He builds a house for his identity, and, like any well-kept house, it operates in a sustained level of flux, accepting renovations as they come.

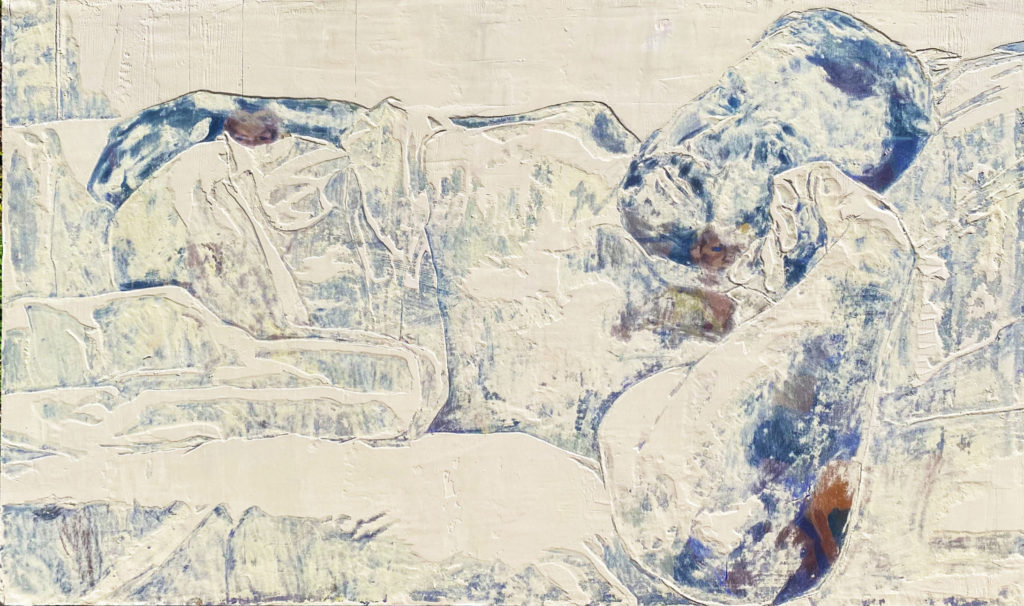

Most of Ruhala’s work is not about the artist at all. Paintings of his partner, Joseph, outnumber any other subject and exude a palpable affection with even Ruhala himself saying,

“The work isn’t just about me, it’s about him [Joseph] at the end of the day.”

In the vein of artists like Alice Neel and Egon Schiele, Ruhala captures his partner with veristic honesty and indefatigable passion. With every subtle feature blown up and overaccounted for, he imbues the subject with the whole weight of his expression. And this weight manifests in unconventional uses of joint compound (usually a construction material). Once this weight builds up, a sturdy tenderness stands simply because it was made to. The household materials eek with potential, a potential I hope to see realized in his future career.

As for Greenwald, his work is much less alive. Watercolors of broken down and rusting cars make up what looks like an ad for automobile repair. You could almost slap on the name Clay Cooley and hang it above the tire sales rack. This is not to say his work is lifeless advertisement, but instead that his watercolor technique is so refined that his art looks photographic. These southwestern still-lives appear straight out of a Tennessee Williams production, encapsulating the drawling decay of southern life. Not just ordinary southern life, I’m talking sweet tea and muddin’ southernlife.

Even though like in “Three Sedans in Marathon, TX,”Greenwald gives specific call-it-like-he-sees-it descriptions of the pieces, the subjects still seem distant and obscure. The repetitive blue sky and green grass only work to obfuscate the specificity of the narrative. A conceptual abstraction betrays his fastidious technique, trading truth for fiction and vice versa. Ultimately, these could be anycars in anypart of Texas (if only you ignore their titles). In a way, quite opposite Ruhala, Greenwald’s hyper-realistic detail distances the viewer from the narrative’s captured moment.

The work in “Ephemera(lity)” is ultimately archaeological. Whether memories or degrading metal, the narratives exude an anachronistic presence not unlike fossils in a museum. The impossible coupling of both past and present leaves the latter off-kilter and irrevocably altered. Just as the fossil cannot and will not reassert itself, Ruhala and Greenwald present moments frozen in time.

In the same vein, Ruhala and Greenwald erupt at Ro2 Art with work you would expect from mid-career artists. It is not often you catch burgeoning talent before they’ve “made it.” Don’t miss this moment – it may not happen again.

“Ephemera(lity): Tad Greenwald and Eli Ruhala” is currently on view at Ro2 Art in the Cedars, through Sept. 4.