Site revives social media postings

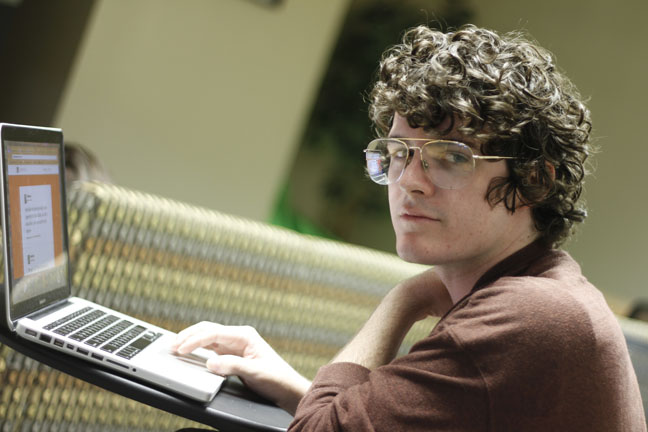

The perception of the Internet as some innocuous pastime where all transgressions are forgiven with a click of a Delete button prompted Bradley Griffith, an Emerging Media and Communications, or EMAC, graduate student, to create a program that would remind users of how lasting one’s actions on the Web can actually be.

Griffith’s program, aptly titled Undetweetable, sought to recover deleted Twitter posts, or “tweets,” thought to be forever erased into the technological ether and offered this service to the masses through a website of the same name.

Controversial tweets like Chris Brown’s homophobic insults towards fellow R&B singer Raz-B or career-ending indiscretions such as former Senator Anthony Weiner’s sexually explicit photos can be replayed by Undetweetable with a simple search of the person’s username. Despite how quickly these public figures attempted to mitigate their social repercussions by removing their comments, their legacy remains chiseled into the seemingly imperceptible wall of coding that governs the Internet.

“It should be known, and was indeed the initial purpose of our site to illuminate, that our functionality is not only easy to implement, but also an ongoing process,” Griffith said in an email. “One’s deleted tweets are never actually deleted, and likely stored by more companies than Twitter alone. Our intention was to spotlight the practice in a sensational way in order to open discussion about where we are going as a society.”

The site proved to be the sensation Griffith had hoped for, and much sooner than he had anticipated.

“It took off like a flame on the Internet,” said Dean Terry, director of the EMAC program. “We expected it to go on for several weeks before it got so popular that we had to shut it down, but it only went for like five days before it got so popular that it nearly killed our servers.”

After exposure from sources like the Washington Post and Gizmodo, Twitter caught on to Griffith’s website and immediately asked that it be shut down since Undetweetable violated Twitter’s API Terms of Service. The site was discontinued without any resistance because its purpose was served.

“Twitter’s request to shut down Undetweetable was a badge of honor,” Griffith said. “Definitely something that I intend to print out and frame. That is, however, almost entirely because Twitter is a large and recognizable corporation — getting their attention is, in a way, a validation of my efforts.”

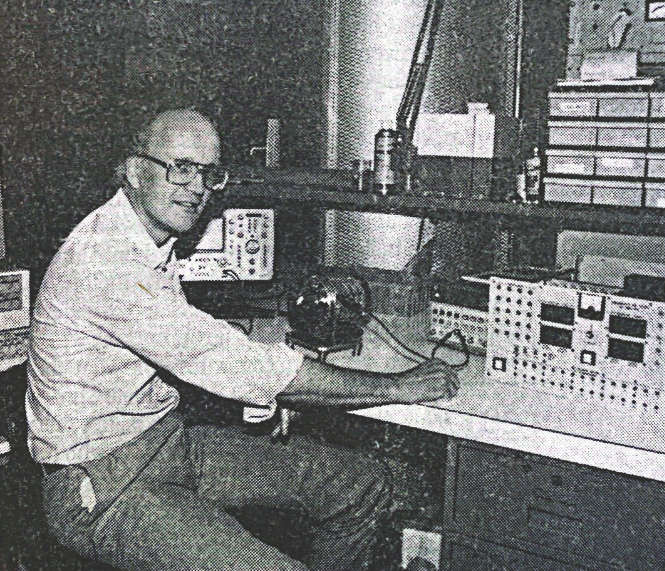

Originally, the concept behind the program was just a budding idea of Terry, which would serve as a teaching tool for students to understand the brevity of the Internet.

“I wanted to have people pay more attention before they hit send on a social network. I wanted them to think more about what it means to share your information and who owns it and where it goes because I think it tends to be too casual,” Terry said.

The collaboration between teacher and student proved to be successful beyond what they had hoped for. It brought attention to the question that if university students in a research class could take one’s data for an educational project, what other entities could also gather one’s information and for what purposes?

Alex Hays, an EMAC graduate student and friend to Bradley Griffith, is no stranger to new media and the online community. In addition to being the systems-admin for RadioUTD, he also manages multiple websites and is an avid user of Facebook, Twitter and other social networks.

Hays likened the monitoring activities of social networking sites to that of a “black box,“ which is a device that quietly tracks the activities of airplanes and cars in order to see how their accidents occurred. He also mentioned how big businesses and employers could make apps which could track users’ Facebook wall and perform search queries for keywords like “weed” or “alcohol.” And while such apps might be an extraneous, third-party pursuit, this tracking and monitoring is integral to how Facebook operates.

“I don’t think Facebook would exist if they didn’t do that, because that’s how they generate a lot of the ad revenue,” Hays said. “I think it’s a scary time that we’re in when that’s how it is and that’s just the de facto nature of that form — we’re the ad dollars. It’s like we’re the products, and that’s scary.”

As Undetweetable served its purpose in raising awareness to the issues of online activity that many people might not be aware of, Griffith and Terry have decided to continue their partnership in the EMAC department.

Griffith said to expect their next creation sometime this fall.