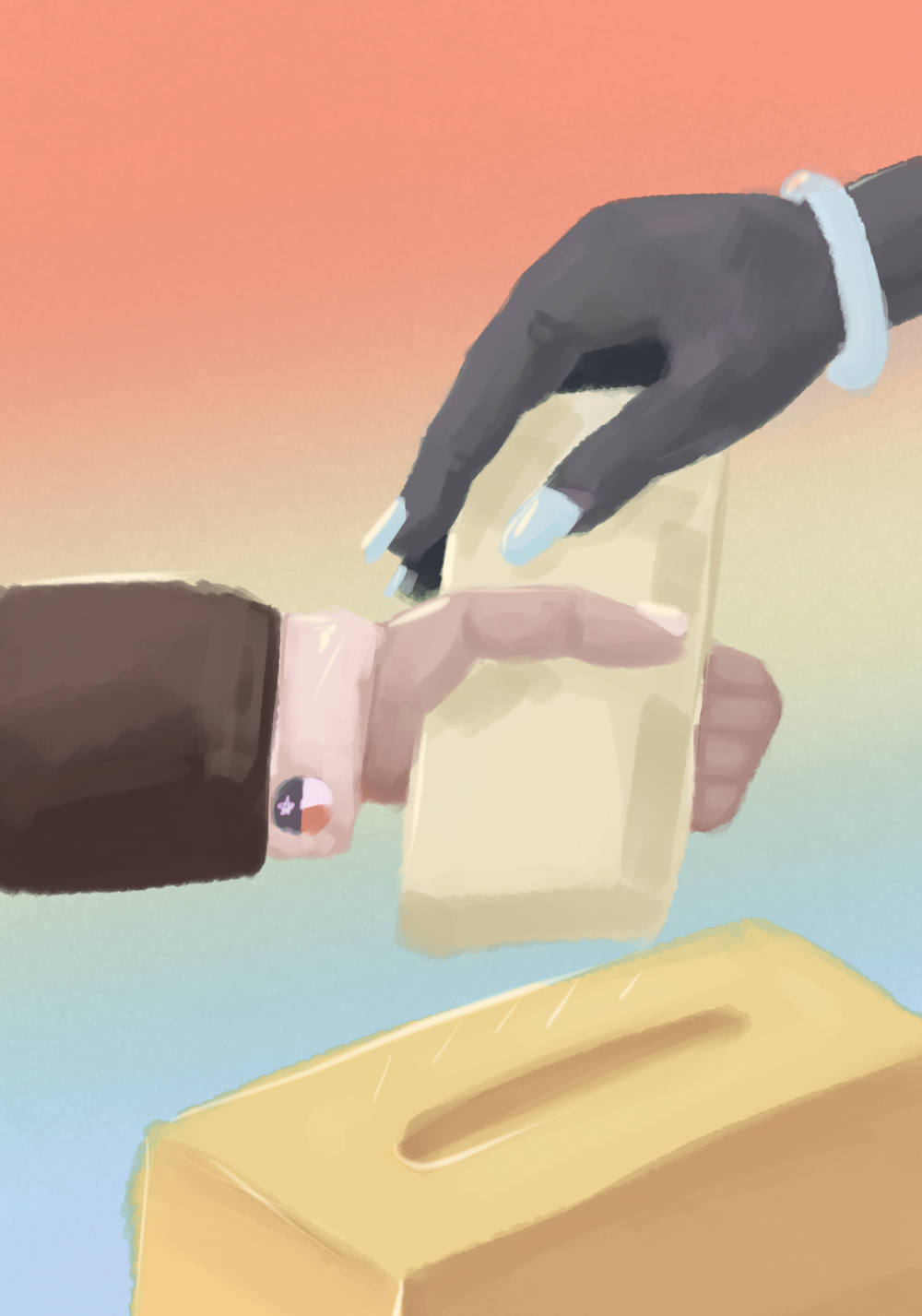

Taking away the most convenient location for college students to cast their ballots is an obvious attempt at disenfranchisement and must be condemned.

Disenfranchisement is exactly what Republican Rep. Carrie Isaac is trying to do by filing House Bill 2309. The proposed legislation would remove polling locations from Texas colleges and universities.

“We must protect places of education where our children and young people gather,” Isaac said in support of her “Texas Campus Protection Bill.”

At a time when college students are voting in record numbers, with a 67% turnout in 2020, conservative lawmakers are using the mantras of secure elections and public safety to discourage young people’s vote. They know the demographic they are targeting. NPR found that roughly 30% of eligible Gen Z voters aligned with Democratic candidates, as opposed to 24% with Republicans and 28% with Independents.

This bill is just one example in a string of attempts by Texas leaders to discourage liberals from voting. In 2014, student IDs were deemed an unacceptable form of identification to vote, while concealed handgun licenses were “OK.” In the last few years, Gov. Abbott has ended 24-hour and drive-thru early voting initiatives and, before the 2022 midterms, crafted stricter requirements for absentee ballots.

Since 2021, a valid ID or the last four digits of your social security number has been required to file mail-in ballots, resulting in 25,000 rejected ballots in Texas’s April primary. The same law made it a felony to distribute mail-in ballots to voters who did not request them.

Isaac articulated concerns with Texas’s two-week period for early voting. She said it was “too long” in a recent interview, despite it having a positive effect on voter turnout.

While conservatives say they are centralizing the state’s vote, they know that fewer locations and less time means more Republicans benefit. The Guardianfound that in transitioning to “countywide polling places,” racial minorities in Texas had to travel the furthest and were less likely to vote than non-Hispanic whites.

This might have lessened the chance of voting at the wrong precinct, but it decreased the number of available polling locations by half compared to the traditional precinct-based system. This is particularly important in the state of Texas, which, according to a study by The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, leads the country with 750 polling location closures.

Transportation has a significant effect on voter participation. Pew Research found that voters who “lack automobile access and fast public transportation” were less likely to vote, and the Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement discovered that two of the top eight reasons young people didn’t vote were because of “inconvenient hours/polling location” and “no transportation to polling place.” Moreover, 29% of all youth didn’t vote because of transportation reasons.

In an interview with KTLV’s East Texas News, Isaac dismissed the need for reliable transportation, citing university busing, while acknowledging that not all education institutions offer the same level of services.

If Isaac’s bill is implemented, students who depend on on-campus polls would have go out of their way to vote. Finding reliable transportation is another unnecessary cost for a population already pressed for cash. Ultimately, college campus restrictions are more ploys to eradicate polling locations from liberal areas and discourage Democrats from voting.

While Isaac claims this bill protects younger Texans by excluding non-students, it is not the most efficient way to increase public safety. Isaac said a 2017 stabbing at UT Austin and last year’s Uvalde shooting at Robb Elementary prompted her to write the legislation. She also plans to draft a similar bill that would prevent K-12 public and charter schools from hosting polling sites.

“Parents’ concerns have been magnified,” Isaac said. “We must protect places of education where our children and young people gather.”

But as to how exactly those two events were related to polling and elections, Isaac couldn’t provide a clear answer.

In an emailed statement to The Mercury, a spokesperson for Isaac said that “individuals who committed the crimes were not supposed to be on campus.”

In the UT Austin example, the perpetrator was a biology student who injured three and killed one of his fellow classmates. Yes, in Uvalde, the killer was not supposed to be there, but the school was not a polling location, nor was the time of the shooting close to an election. It was tragically during the last week of school. Isaac’s point is completely unfounded, since non-students could easily bring violence to a campus on any regular day of class.

Even if election-related violence is on the rise, moving polling locations from college campuses to other areas would merely “transfer the risk to another, equally vulnerable public location,” based on data from the ABS Group.

If lawmakers want to enact real change, they need to find a middle ground between sensible gun restrictions and campus security measures. Isaac said she wants to increase the number of former police officers in K-12 schools. Why not increase security on college campuses during elections instead of removing the location entirely? Though somewhat related to protecting schools, the bill’s benefits don’t outweigh the costs of disproportionately affecting young people.

Finally, though Isaac’s bill hasn’t made it through committee, it could hurt UTD more than any other college in Texas. Last semester, UTD hosted polling locations for Dallas and Collin County, the second and sixth largest counties in the state by population. Beyond students and faculty, the bill’s implementation would widely impact adults in North Texas who rely on UTD’s facilities.

Leave a Reply