The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, or FIRE, has flagged UTD as a red-coded school for freedom of speech, meaning they believe several code of conduct policies go against language protected by the Supreme Court.

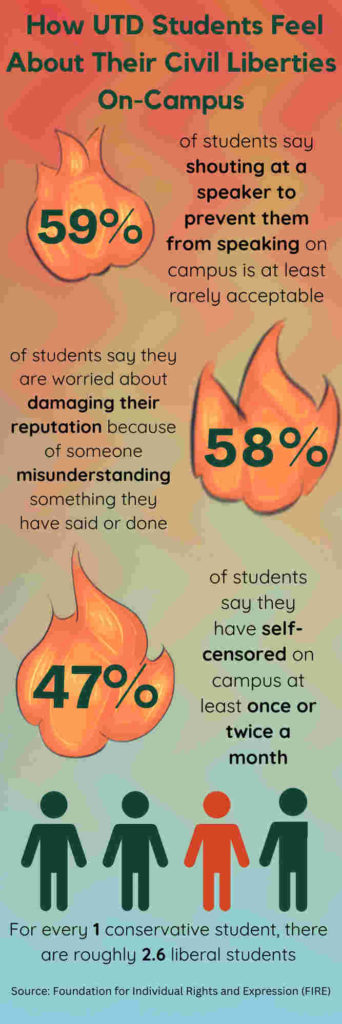

A FIRE survey including 247 enrolled students recently ranked UTD No. 114 out of 248 campuses in free speech and tolerance. Despite being one of the most diverse universities in Texas, according to FIRE’s ranking system, where higher scores represent higher freedom of speech, UTD is ranked No. 97 for tolerance of liberal beliefs but only No. 36 for tolerance of conservative beliefs. It is rated No. 98 for admin support, No. 121 for comfort and No. 65 for disruptive conduct response. Student complaints to FIRE included the perception that they need to self-censor due to “liberal agendas.” Student respondents also said they avoided discussing the divestment resolution, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and stances on abortion out of fear of social backlash.

FIRE is one of the largest nonprofit civil liberties groups in the nation, with a revenue of $16.1 million in 2021. FIRE focuses on public education campaigns, individual case advocacy and policy reform. Since its formation in 1999, it has advocated against UTD twice, first when it demanded UTD stop its investigation into computer science professor Timothy Farage in 2022 after his tweet calling for a “cure of homosexuality.” FIRE also recently defended computer science graduate Cody Hatfield from a deferred suspension after a verbal altercation with a parking attendant.

FIRE has flagged six student code of conduct policies for going against the First Amendment. The only red-coded policy which FIRE has deemed unconstitutional is UTDSP5005, the Student Grievances policy, which The Mercury covered in its story on Hatfield. Specifically, the red coded policy focuses on section 51.02, which addresses sexual harassment, complaint procedures and appeal procedures.

“Such harassment is defined as unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature,” according to the policy. “Suggestions that academic or employment reprisals or rewards will follow the refusal or granting of sexual favors, also constitute sexual harassment.”

The Mercury obtained a private letter that Griffin sent to President Richard Benson on Jan. 27, 2023 in regards to the offense, where FIRE argued that UTD’s definition of harassment is too broad. Griffin said that the policy goes against the Supreme Court’s ruling that to be harassment, speech must be “so severe, pervasive and objectively offensive” that it damages the victim’s academic career enough to essentially deny them equal access to opportunities.

“Interestingly enough, the university also maintains a definition of sexual harassment that does meet the Court’s standard in [Davis v. Monroe] in the UTDBP3102: Sexual Misconduct Policy,” Griffin said. “This policy earns a green light rating from FIRE. We’d advise the university to utilize this policy for all instances of peer sexual harassment.”

The university has yet to elaborate why there are language differences between different policies, in which one no longer meets the Supreme Court’s definition. There are five UTD policies flagged as yellow-coded, meaning the policy is too ambiguously worded and, in FIRE’s interpretation, could allow administrative abuse or manipulation against students. UTD’s yellow-coded policies include the definitions of harassment for nondiscrimination, harassment defined in sexual misconduct, the interpretation of verbal abuse, the prohibition of sexually explicit material on university information systems and the restriction of posting flags in high residential areas.

While the latter policy is marketed as a safety measure that prevents damage from falling debris, FIRE representative Mary Griffin explained the nonprofit’s position against UTD by referring to the court definitions found in 1999 Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education and 1972 Gooding v. Wilson. According to FIRE, UTDBP3090: Nondiscrimination, UTDBP3102: Sexual Misconduct Policy and UTDSP5003: Student Code of Conduct each define harassment in a way that does not meet the bar set by Davis v. Monroe.

“The UTDSP5003 provision bans ‘verbal abuse’ along with conduct the university may legally prohibit like physical abuse, threats and intimidation,” Griffin said. “‘Verbal abuse’ is an amorphous, overbroad term that could be used to punish constitutionally protected speech.”

Griffin also said that while UTD was correct to ban illegally obscene sexual content, the written policy for UTDBP3096 was again too broad and could target “sexually explicit material” that is protected under the First Amendment. According to the 1973 Supreme Court case Miller v. California, for content to be considered obscene, it must appeal to sexual interests, it must depict or describe “sexual conduct or excretory functions” and it must lack literary, political, scientific or artistic value. Sexually explicit content may be generally vulgar or profane, but it is protected speech as long as it isn’t obscene.

“For example, under the policy as currently written, a professor teaching a course on human sexuality could be subject to punishment for emailing a screenshot of a sexual, but not legally obscene, image in a PowerPoint presentation to students that touched upon a class discussion topic, like gender roles,” Griffin said.

The Mercury reached out to representatives from the Office of Provost, the Policy Office and the Office of Community Standards and Conduct for statements on FIRE’s policy rankings. None have replied for comment on the matter.