Food service workers across campus are seeking to unionize amid allegations of wage withholding, harassment and other unfair labor practices against Chartwells, the primary food service provider at UTD.

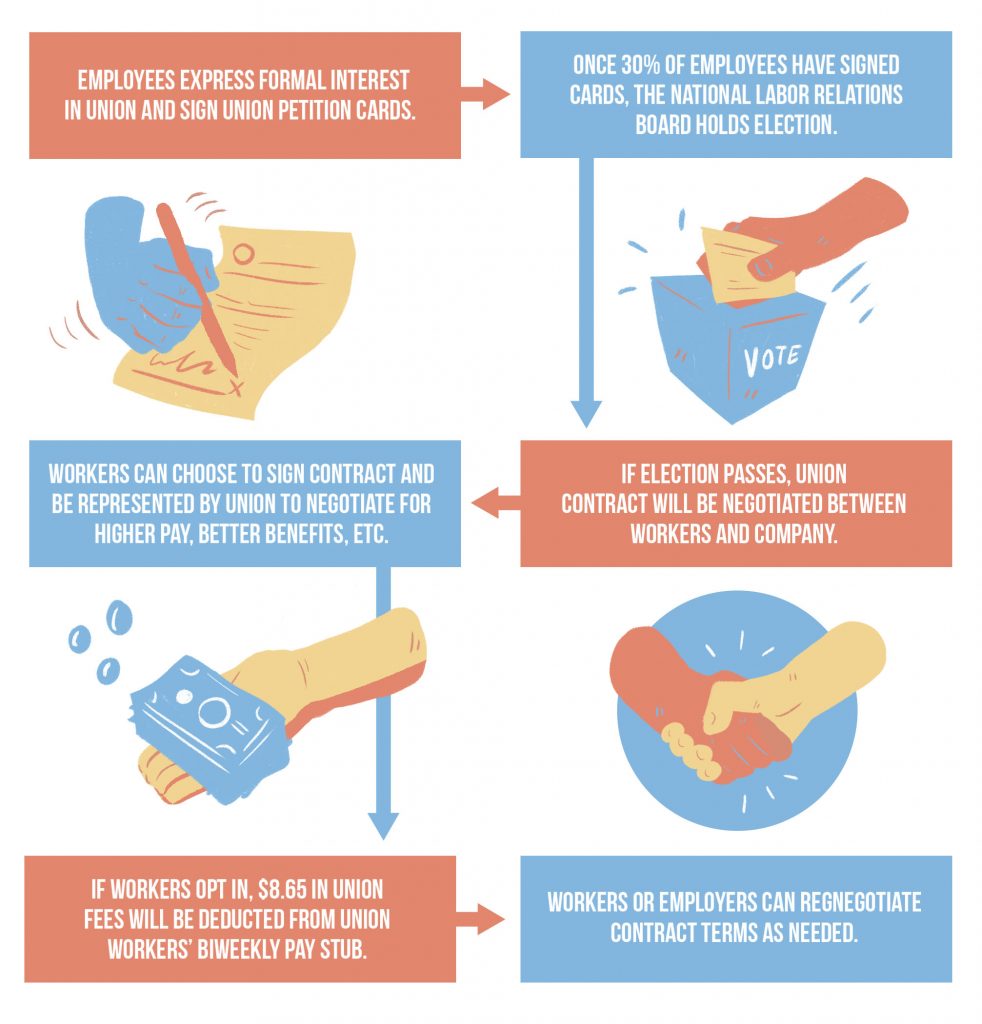

In April, Chartwells workers at UTD contacted United Food and Commercial Workers, a group that assists workers in negotiating collective bargaining contracts with their employers. Shelley Seeberg, a campaign manager with the national office of UFCW, said these accusations aren’t unique to employers such as Chartwells, but are part of a larger national push for better wages and working conditions.

“When there isn’t a union contract, we see things like favoritism, pay inequities (and) high-cost health insurance,” she said.

Compass Group, the company which owns Chartwells, and Chartwells Resident District Manager for UTD, Steven Goodwin, declined to comment. UTD’s Office of Auxiliary Services, the office that coordinates with Chartwells, did not respond to requests for comment.

The Mercury spoke to five former and current workers and supervisors at Chartwells about their experiences as employees and their involvement with the union movement.

Since the effort formally began in May, numerous employees at UTD allege Chartwells has targeted them unfairly for suspected involvement with the union. The Mercury obtained copies of anti-union literature which was distributed among workers. According to police reports, two union-affiliated individuals were banned from campus in October after a complaint was filed by the Office of the Assistant Vice President of Auxiliary Services.

The reports, obtained from UTD PD, state that UCFW organizer Cassidee Griffin was issued a criminal trespass warning on Oct. 16. Griffin said she had purchased food from Smash’d and had sat down to eat when she was approached by three officers. The same day, a former employee who had expressed interest in the union was also issued a criminal trespass warning and asked to leave campus.

A university spokesperson justified the decision to remove Griffin in an emailed statement, stating that UTD property and buildings aren’t open for public assembly and speeches, but that their use is restricted to university-related programs and activities. Since the incident, organizer Bricia Garcia said UFCW hasn’t sent any other organizers to campus.

“We don’t know what’s going to happen and what to expect,” Garcia said. “We don’t want another citation, especially since we found out there’s no appeal process.”

Seeberg said that shortly after trespass warnings were issued, Compass Group gave verbal commitment to support the worker’s rights to unionize. Several workers said that despite the promise, they still felt targeted for expressing interest in the union.

One worker said she suspected managers were discouraging her coworkers from speaking with her after she publicly disclosed her involvement with the union. The worker asked to remain anonymous, citing fears of losing her job and further bullying by management.

“I’ve had a couple of employees tell me not to talk to them because they were afraid managers would see them,” the worker said. “I feel like I’m being followed, and managers will ask me my whereabouts constantly.”

The worker said even before she made her involvement with UFCW public, harassment, favoritism and mismanagement was commonplace.

“Never in my life have I seen any (employer) treat people so badly,” she said.

Several employees reported incidents of withheld payments. One of them is Cristian Otero, a night supervisor at the Student Union. Otero said though he was told he was to be paid biweekly, he didn’t receive a paycheck for the first six weeks of employment.

“I (was) really thinking about quitting,” Otero said. “I needed the money and I have bills to pay.”

Otero said he and other employees weren’t given access to their paystubs, and when they finally were paid, their wages were issued on a reloadable debit card.

A former student worker at Starbucks, who requested anonymity out of concerns of harassment, said that for the first two months of employment, he wasn’t entered into the clock-in system and couldn’t clock in without a supervisor. He said after the first month, supervisors were told to stop helping employees clock in.

“For a month, I wasn’t able to clock in at all, and I didn’t receive pay for that period (until after I complained),” he said. “Then I didn’t have access to my pay stubs, so I had no way to verify that they were paying me for the right number of hours.”

The Mercury obtained a copy of the student worker’s contract, which stated he would receive a weekly paycheck. The student worker said he was later verbally told he’d only be paid twice a month instead. He said when he tried to bring up the problems with management, managers tried to avoid speaking with him face-to-face, and later cut his hours.

“I knew they were agitated because I was pointing out issues,” he said. “Then they cut my hours from 30 to 15. They said they didn’t need me there, but later would try to pressure me into taking shifts last minute on my day off.”

Otero said he’s seen workers verbally reprimanded for discussing wages. He said he was told such discussions were against company policy. The National Labor Relations Act protects employees’ rights to discuss conditions of employment, including pay. A 2014 federal mandate issued by the Obama administration further protects this right.

While employees of a federal or state entity, such as UTD, are not covered by the provisions of the National Labor Relations Act, Chartwells is an independent business contracted by the university to operate dining services. Its employees are considered private sector workers.

According to data from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s living wage calculator, a living wage for a single adult in Dallas County consists of an hourly rate of $11.15 per hour for 40 hours a week.

Otero said when he was promoted to supervisor, the work became harder, but he was not compensated to make up for the promotion. Other supervisors also confirmed this practice, stating that managers had informed them verbally of new responsibilities and a new title, but they never saw a corresponding increase in pay.

For two years, Frances Sanchez worked for Chartwells in Dining Hall West before resigning in October. Sanchez is a single mother and initially took the job to support her three children. Sanchez said when she was promoted to supervisor, she was told she would receive a raise to $14 an hour. She said that raise never came, but she ended up having to work extended hours in her new position.

“It got to the point where I barely ever saw my kids,” Sanchez said. “They are the most important part of my life.”

In Dallas County, MIT’s living wage calculator estimates a single parent with three children must work 40 hours for at least $33.45 an hour to make a living wage. Earning $12.18 an hour, Sanchez was making about a third of that.

Otero said he and many other workers don’t have reliable transportation and have to rely on ridesharing apps in order to get to and from work. A round-trip commute to and from his home off campus costs him $30, which represents around three hours of work.

Griffin, the UCFW organizer who was banned from campus, began speaking with Chartwells employees in May. Griffin said that she’d been told wage disparity and stagnation were common issues at Chartwells, especially among international students workers.

Without special authorization, students with a F-1 visa are not allowed to seek employment off campus. For that reason, international students represent a more vulnerable class of worker, according to a report by the Center for Immigration Studies.

“There’s a huge wage gap,” Griffin said. “There are international student workers who’ve been (at Chartwells) for three years and they’re still making $8 an hour.”

Griffin said limited employment options could be one reason why international student workers might be afraid to speak up and ask for a raise.

“(Management) knows (international) students are desperate to make some money, so they’re willing to work for minimum wage,” a supervisor said. “These students don’t have a lot in this country — and they don’t always have enough to eat.”

At UTD, international students cannot take work study jobs, and can only work 20 hours a week at most. Multiple anonymous sources confirmed that international students make between $8 and $8.50 an hour, which averages to $660 per month.

“(Management) keeps international students at low wages because they can,” Griffin said. “They’re treated differently, too. Problems aren’t handled as quickly as they are with full time employees or (domestic) student workers.”

Three of the employees who spoke to The Mercury allege that a Chartwells manager had been sending female international students illicit texts, asking them to wear tighter clothing, wear their hair a certain way or to wear more makeup. The employees also said another international student was asked to go out with a manager over text.

“She didn’t want to go public with her story because she said she didn’t want to go through the pain again,” one worker said. “I just hope she’s able to talk to someone. I don’t want her to feel bad like that for the rest of her life.”

Sanchez said that as a supervisor, she felt it was part of her job to look out for the employees under her. Although she has since left her position at Chartwells, she said she remains close with some of the student workers — and without a collective voice, said she’s concerned for their safety.

“After an incident with a manager, one girl was rocking back and forth, saying, ‘I need this job, I need this job,’” Sanchez said. “No one should feel that way — ever.”