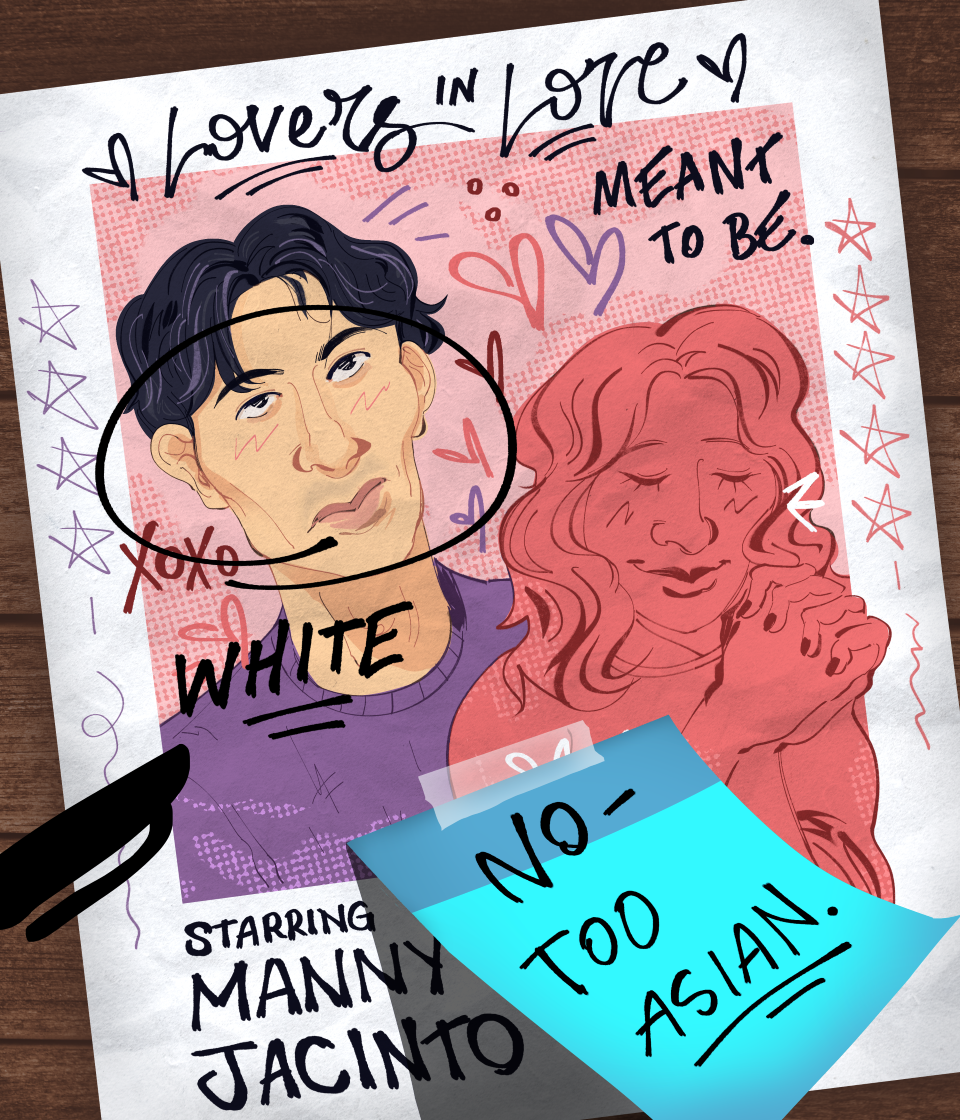

The burden of having to give the most coherent, objective and unbiased information in the vast works of American government is put on the shoulders of today’s civics professors. Their job at the basic level is to educate, but they must also moderate discussion. In the age of trigger warnings, safe spaces and microaggressions, it’s hard to see past the overall babying effect of universities; nonetheless, when it comes to faculty associated with government and politics, they do not shy away from the responsibility of teaching the most controversial subjects. The consensus of political science professors is that they’re constantly indoctrinating students and blending their own values with the curriculum. In reality, the instructor’s political loyalties have almost no effect on their students. At UTD, I observed this in several classes: in any given lecture, when a controversial topic was brought up for discussion, restraint and the refusal to give credence to one point of view at the expense of another were regularly displayed.

The first rule in maintaining order in a classroom is to not reveal your political leanings. In a public policy lecture I attended, the professor was attempting to manage heated exchanges between an Iraq war veteran and a freshman over 9/11 and America’s presence in the Middle East. There were accusations of “invading for oil” and ulterior motives with Vice President Cheney’s business ties. The professor let the contention fizzle out and after someone asked, “Was there any legitimate purpose to the Iraq War?” he replied, “I believe he had good intentions,but that doesn’t mean the president is justified.” The demeanor of the professor allowed for no one’s agenda to be satisfied. The veteran retained their pride and the freshman felt enlightened. George W. Bush’s character was removed from the discussion, while a critique of executive overreach was acknowledged in all its contemporary forms. Civics professors gain the respect of their students when they don’t make their political affiliations obvious.

In a legal class, the jurisprudence of Roe v. Wade was on the list to deconstruct. Unlike issues where the country has largely moderated its views, like gay marriage, abortion has continued to be an emotionally charged policy issue since the culture wars of the 1960s. After the background was read, a student asked about “packing the Supreme Court” and whether the Republicans would overturn Roe or even the past election. This professor made an exception to give his opinion on the matter because the Senate had already voted on it, but simultaneously pacified students who worried about issues reaching a 6-3 conservative swing court. He stated that if Democrats expand the court so would Republicans, and eloquently conveyed population growth and the Constitution’s lack of specificity regarding the number of required justices as his reasons for expanding the Court. Instead of using the lectern as a pulpit, an alternative response was introduced and multiple well-reasoned perspectives on the issue were presented without the professor revealing a political north star guiding his every belief.

History holds a similar importance in teaching students about government, yet the discipline has recently been treated as ammunition for much broader partisan warfare. I observed lectures where the class’s goal was to cover social issues in a historical frame yet would result in teachers preaching to the presumed choir or a student taking command of the floor and forcing everyone else to nod in agreement. Instances where a student complained about the lack of diversity in a book about history’s greatest thinkers and a professor pushed Trump’s name in a session over who historians think is the worst president in history have convinced me that those environments are geared towards cheap emotion and scoring political points. Contrastingly, in a recent constitutional law class where the concept of Black voting rights was said to have existed in Maine and Vermont’s constitutions, the instructor inquired, “Could black people vote in the early republic years?” Students responded and refuted, backing their claims with evidence from the textbook; some even found common ground. In all these situations, the professor’s posture was key. They were not beholden to the most pompous voice, encouraged the timid to interject, and most importantly, intentionally called on people who don’t normally raise their hand. Additionally, I have observed that civics professors seem to have several methods of maximizing their neutrality: political round tables before class, student polls and not tempting themselves with the low-hanging fruit of partisan discourse.

The modern college campus has turned professors from lecturers to moderators of student exchanges, but at some point, when students and teachers use the curriculum to achieve partisan ends, an objective voice must stand in sharp contrast. This is not a gloss of all political science professors, but it seems that those with the most challenging subjects to teach have proved themselves most adept to the task at hand. They have stayed true to UTD’s motto: “A cultivated mind is the guardian genius of democracy.” Civics professors are unique because they don’t misuse their power despite having many opportunities to do so. Instructors in other departments should learn from and model their behavior.