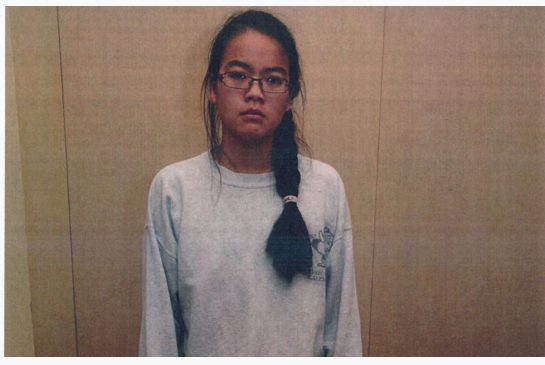

When I first heard about Jennifer Pan, a Vietnamese-Canadian girl who hired hit men to kill her parents, my initial reaction was utter disbelief. But then I thought about it. Was the concept of an Asian girl feeling so suffocated by her parents that she took a step as drastic and crazy as ordering a hit on them that hard for me to believe? Not really.

In a nutshell, Jennifer Pan is a typical Asian girl with typical strict Asian parents who have high expectations for their daughter. In high school, she began to fall short of her parents’ high academic expectations. Unable to face telling her parents about her shortcomings, she fabricated a series of lies by faking false report cards, her high school graduation, her college enrollment and later, admission into pharmacy school.

Eventually her lies went too far and her parents found out. They cracked down on her and she couldn’t take it anymore. Pan conspired with her boyfriend to have her parents killed in a fake robbery. She was found guilty of murder and attempted murder earlier this year.

As I read further and further into her story, so much of Pan’s life resonated with me. While I would never harm my parents, there are days when their helicopter parenting becomes too much for me to handle.

My parents are Vietnamese immigrants — refugees to be exact. Their story is like that of many refugees from Vietnam: they escaped on a boat to Indonesia where they applied for and waited to be granted immigration to the United States. Once my parents got here, they labored and studied with the hope that my sister and I would have a better life in the United States than we would have had in Vietnam.

By most definitions, they’ve succeeded. They worked hard to support themselves and their siblings through college. They both have prosperous careers and I’ve been lucky enough to have their financial support whenever I’ve needed it.

That being said, perfection was an unyielding expectation in our household. They weren’t tiger parents, though I wonder if sometimes they wish they had been. My parents always reminded my sister and me that they wanted us to strive for our absolute best.

However, I was petrified when I had to take home my first report card that didn’t contain all A’s. I wasn’t a perfect student, but I tried my best to be as close to one as possible. I was always afraid to show my parents my failures because I didn’t want them to feel like their sacrifices for my sister and I were for nothing.

I was never allowed to go to sleepovers. Whenever my parents were wrong, there was never an apology or an explanation — just an expectation that it would never be brought up again. Even now, as a 22-year-old going into my second year of graduate school, I still have to call my parents every single day at 9 p.m.

When I go home, I am hesitant to make plans with my friends if I have to run them by my parents. The first and only time I introduced a boyfriend to my parents led to an interrogation that was awkward for me and petrifying for him.

My parents are textbook examples of Asian parents. They are the kind of parents it seems like Pan had. It wasn’t hard for me to believe that Pan’s parents restricted her computer and phone usage: my parents have always threatened that if I step out of line, even when I am away at school, they would not hesitate to pull me out and make me come home.

In that sense, I get how her parents could have driven her completely crazy. I understand how she could have felt like she didn’t have any other option. I recognize the feeling of knowing you’ve let your parents down. I get all of that. What I don’t get is how that translated into a desire to kill her mom and dad.

I definitely don’t want to paint Asian children as ticking time bombs. I love my parents, and I know that their desire for control stems from love.

I’ve also learned that, sometimes, Asian parents have a very singular view of success. It’s hard to convince them that there are many ways to achieve it. I think that ended up being Pan’s problem. She always fell short of what her parents considered being on the “right” path, earning the “right” grades and doing the “right” things. In reality, that path isn’t always for everyone.

When I got to college, my plan was to finish my undergraduate education in three years and then go to medical school. My GPA and MCAT scores said otherwise and that was all that mattered to my parents.

It didn’t matter that I was the only science major working at my school’s student newspaper, keeping up with my studies and winning awards. It didn’t matter that, as a sophomore, my research advisor and the other faculty members in my department named me as one of two students recognized for their research.

None of that counted as being successful because it wasn’t on the predetermined path my parents had chosen for me. One of the hardest lessons I had to learn in college was to not be hung up on what my parents thought was success. And I’ve had to work on that with them. I’ve had to convince them what I was doing was special. I had to show them I was still making a difference and I was excelling in my chosen field.

This upcoming year will be scary for me. It will be my chance to show my parents I have been working towards something important. It’s taken me six years to get to a point where I can take pride in my accomplishments regardless of what my family thinks.

I would never justify Pan’s actions because, quite frankly, her story is no different from mine and many other Asian-Americans’ in the United States. We are all under immense pressure, but as Asian-Americans we have to continue moving forward rather than allowing our shortcomings to define who we are.

At the end of the day, success is not defined by the letters at the end of our names-whether it be M.D., Pharm.D. or anything else-or the number on our transcripts. There are many paths to success; we just need to find the right one for us.