Scores of people dressed as their favorite anime characters flocked to the Sheraton in downtown Dallas for the annual AnimeFest.

Not only was the event a four-day convergence of cosplayers, but also an event that brought in some of the top scriptwriters, directors, and animators in the Japanese anime industry.

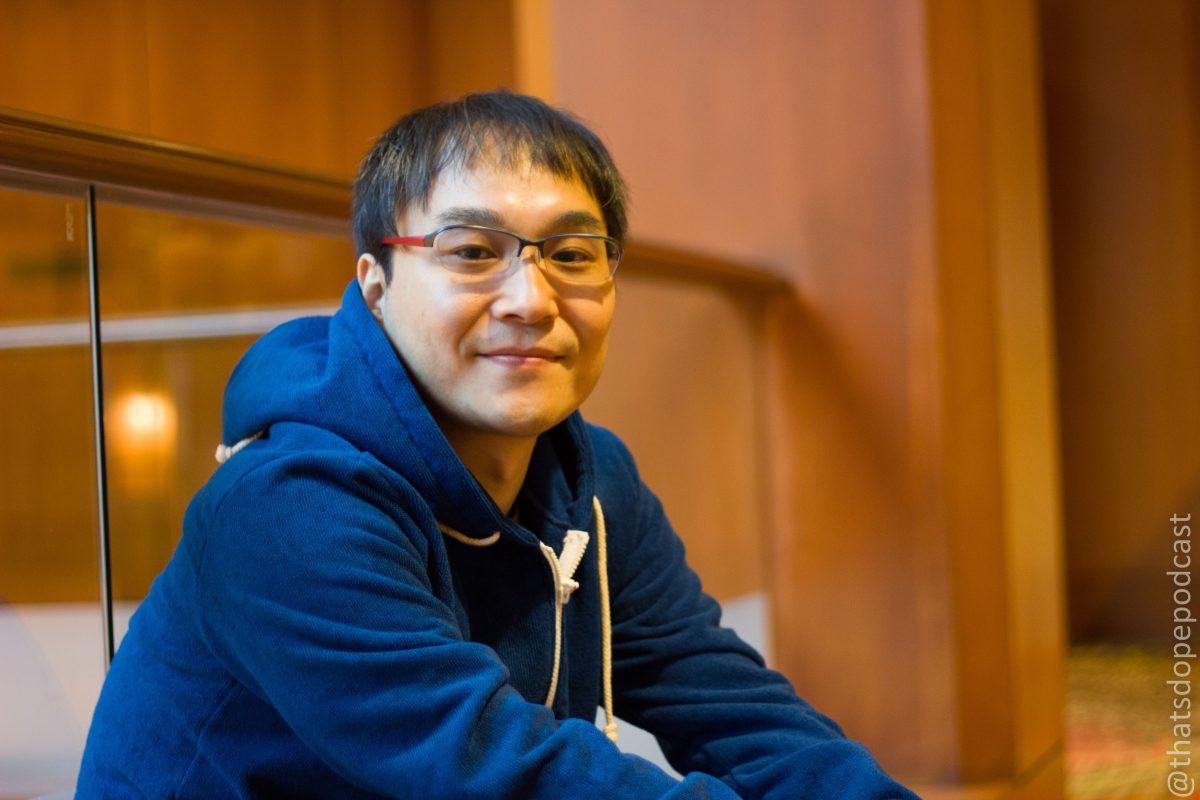

Prominent Japanese scriptwriter Dai Sato spoke about his career, present work and discussed challenges facing students looking to work professionally in the anime industry.

Sato started his career as a sketch comedy writer and got his break at age 28 when he worked as a writer on the critically acclaimed anime series “Cowboy Bebop.” He followed up with a series of popular shows including “Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex,” “Eureka Seven” and most recently, “Space Dandy.”

A veteran of the industry, Sato had several viewpoints to share with students on how to get started in anime.

“It’s very difficult to start your own company,” Sato said, through an interpreter. “But because of the advent of things like Kickstarter, rather than go and search for investors — whether it’s a student or someone well-established — Kickstarter is the recommended way to go.”

Indeed, there have been several successful anime series launched through Kickstarter. For example, producer Masaaki Yuasa recently raised over $200,000 for a project called Kick-Heart.

“The other option is to find a connection within the studio and find a way to promote yourself to that studio,” Sato said. “Returning favors [to colleagues] also helps.”

Nowadays, Sato works through his company, Storyriders, founded in 2007 after he left his music company, Frognation.

Storyriders was created with the intent to combine the music aspect of his previous company, Frognation, with his scriptwriting skills to produce an original work while maintaining full ownership, Sato said. But his team quickly found that there were limited funds to start such a large project.

With regard to students looking to start a company, freelance, or work for a studio, working freelance is the optimal choice for an animator, Sato said. For a student looking to be a scriptwriter, finding enjoyable work is a top priority, although the desired positions may not be readily found.

“For any particular company, look for a job where you can apply yourself as a writer, where you can get your name attached to things, and work your way up,” Sato said.

The concept of globalization was a prominent theme of Sato’s commentary, which he discussed at a panel, joined by “Space Dandy” staff Hiroyuki Aoyama, Shingo Natsume, Hiroshi Shimizu and Kimiko Ueno. Sato discussed the variety of international collaborators from South Korea, France and the United States who were required to complete the project.

“The advent of digital production gives people the opportunity to apply themselves to more globalized projects,” Sato said.

Faster turn-around times for anime production have required outsourcing, which allows more time for the writers, producers and directors to perform their primary jobs. Traditionally, the creation process has occurred in Japan, with touch ups or animation between key frames being outsourced.

In the case of “Space Dandy,” however, the creative process was more globalized. Because it was an original project, it allowed the creators to have colleagues overseas contribute.

In turn, this trend may enable students to participate in the creation process of Japanese anime.

“’Space Dandy’ was not based on a manga or other work, which gave us more freedom to ask friends overseas to contribute,” Sato said.

Looking to the future, the move to 3D animation is a key area students should be aware of in the industry, he said.

“There has been a big change in the industry (toward) adding more 3D animation: things like mechs, spaceships or things with a lot of detail,” Sato said. “For anybody who figures out a way of doing that level of 3D detail in 2D, you’re going to do awesome.”

Categories:

Scriptwriter shares career tips, stories at AnimeFest

August 25, 2014

Story continues below advertisement

0

More to Discover