Aggressive beats and snares à la N.W. A.’s “Straight Outta Compton” or Eazy-E’s “Boyz-N-The-Hood” blare from the theater’s speakers – except instead of English lyrics, the unexpected Irish Gaelic sounds throughout the theater. The lyrical rap of “Kneecap,” a comedy drama released Aug. 2 and first Irish-language winner of the NEXT Audience award, transcends language to connect with the English-speaking audience.

The film stars the members of Kneecap – the eponymous Belfast rap and hip hop trio – themselves: JJ “DJ Próvaí” Ó Dochartaigh, Liam Óg “Mo Chara” Ó Hannaidh and Naoise “Móglaí Bap” Ó Cairealláin. The audience follows the rap trio’s inception, making controversial music with lyrics mentioning heavy drug use during political campaigns in support of the Irish Language Act, an act passed in the U.K. Parliament officially recognizing Irish as a language of Northern Ireland.

The story begins with DJ Próvaí, a music teacher at an Irish-language school, being brought into a police station as a translator because Mo Chara refuses to speak English to the police after being arrested at a rave party. As evidence, Detective Ellis brings in a small yellow notebook that contains Irish lyrics which DJ Próvaí reads and translates, finding them amusing with their explicit mentions of drug consumption. Mo Chara looks visibly worried as DJ Próvaí flips through the small notebook and eventually finds a leprechaun LSD blotter placed in between the pages. DJ Próvaí quickly closes the book. Mo Chara tells him in Irish to choose which side of the table he’s on — the English-speaking police or the Irish. DJ Próvaí chooses the latter. Mo Chara introduced DJ Próvaí to Móglaí Bap, and the three of them start creating music together as Kneecap. Móglaí Bap and Mo Chara are the rappers and lyricists, with DJ Próvaí on the mixers.

As the rap trio continues to rise in the music scene, controversy follows them because of their drug-affiliated and anti-British rule lyrics. At one of their gigs, one of the members pulls down their pants to reveal their buttocks with the words “BRITS OUT” written on each cheek. The fact that they rap in Irish doesn’t help their case either. Those opposed of the Irish Language Act such as the Democratic Unionist Party, a conservative British nationalist party, and the Ulster Unionist Party, a unionist party loyal to the British crown, use Kneecap’s music and drug-infused lyrics as proof Irish is the language of the low-life scum. As vulgar and parent disapproved as their lyrics may be, they pull in an audience that revitalizes a dying language through rap’s inherent protest attitude.

“Kneecap” explores the importance of language and its relation to nationalistic identity. Northern Ireland has had a history of political tensions with the British crown and loyalists, or unionists, as England holds most of the political power. This dynamic is explored in “Kneecap” with Mo Chara’s go-to hook up girl, Georgia, who is from the “other tracks” and happens to be Detective Ellis’ niece. Because she’s from the “other tracks,” meaning not in favor of the Irish Republic, their passionate sex always consists of political disagreements between the Irish and the British at both their climax. It’s a hot and funny juxtaposition – a proud Irish rapper defiant in speaking Irish and the niece of a detective loyal to the crown and its “superior” English language.

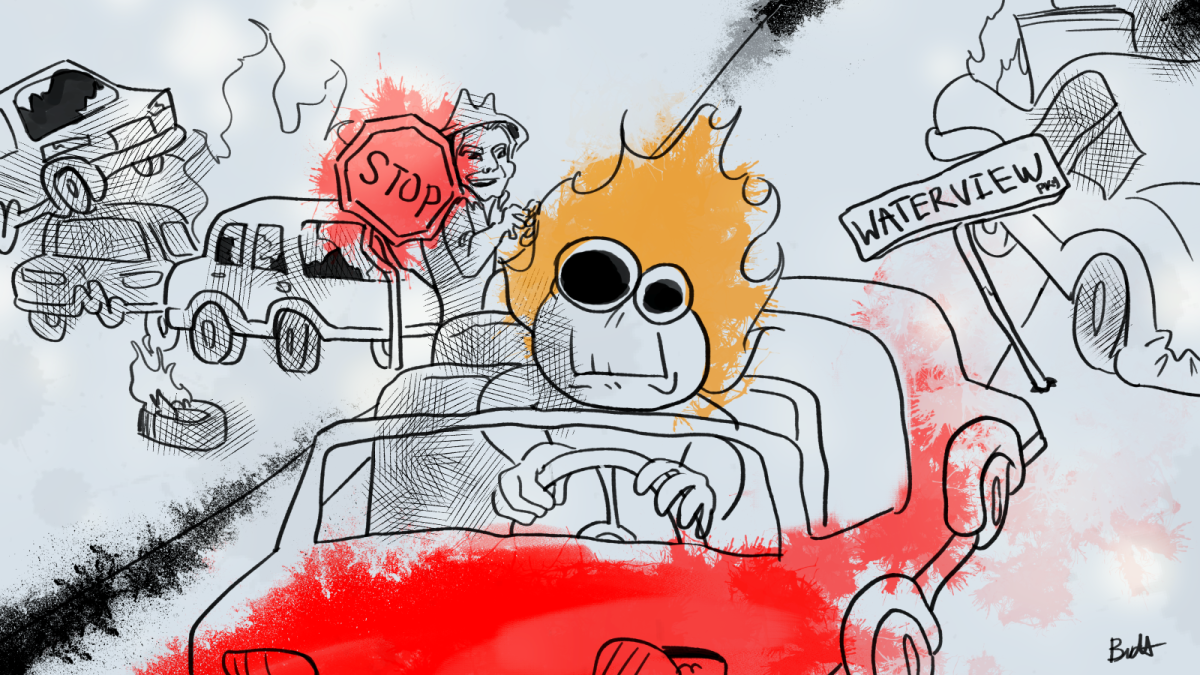

The film uses a plethora of visually captivating mediums, such as doodles and clay animation, to tell Kneecap’s story and their contribution to the growing interest in the Irish language. All three characters’ storylines and personal struggles are woven together perfectly as the group finds musical success. The rap trio turned actors give a new perspective on the power of language through the medium of music. The music throughout the film were actual tracks by Kneecap, giving the film an energizing feel despite the serious topics of language, culture, tradition, imperialism and family.

“Kneecap” is in both Irish and English, with English subtitles provided for all Irish dialogue. However, the heavy Irish accents made the English-speaking sections difficult to follow for the untrained American ear. Subtitles for the entire movie were much needed.

Global interest in Irish culture has risen in recent years with sitcoms like “Derry Girls” and TV series like “Normal People.” “Kneecap” fits right into this Irish media landscape with its comedic raunchiness while simultaneously discussing issues pertaining to Ireland and its people. “Kneecap” is a reminder of the power of language – as Mo Chara and Móglaí Bap say, “every word of Irish spoken is a bullet fired for Irish freedom.”