NASA has selected UTD’s Center for Space Science to build an exploration instrument for its 1995 CRAF mission. CRAF is an acronym for Comet Rendezvous Asteroid Flyby.

In addition, in mid-February the Center submitted a proposal to build another, similar instrument for NASA’s 1996 Cassini mission to Saturn, said scientists at the Center.

The two missions will use similar, general-purpose spacecraft and gather similar types of data.

“Within NASA it’s one project called CRAF/Cassini,” said Dr. Rod Heelis, a space scientist who has been at the Center since 1973.

CRAF is “designed to rendezvous with a comet, the Kopf comet,” said Dr. Heelis. “The idea there is that you send the spacecraft out so that it moves in the same direction as the comet.

“One of the neat things about it is that you can equalize the speed of the comet and the space-craft. So then, you see, they’re almost stationary with respect to one another, and you can make diagnostic measurements of its atmosphere and its interaction with interplanetary space,” he said.

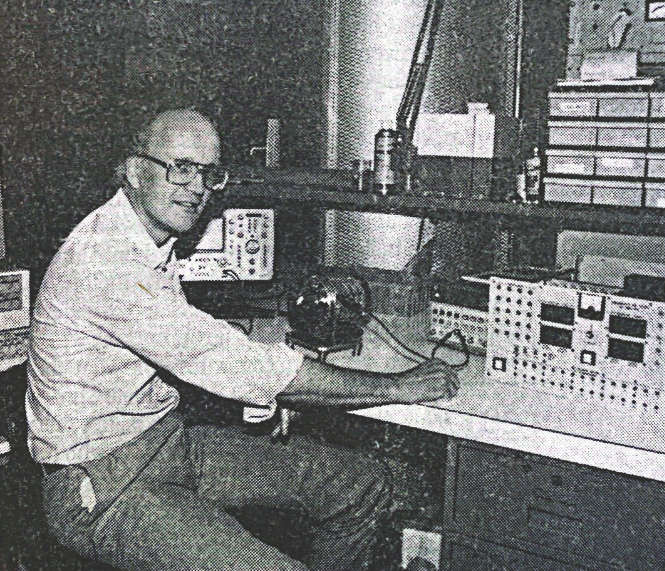

“The instrument that makes these diagnostic measurements will be built at the Center,” he said. “We cut the metal, make the printed circuits, and it’s all bolted together right here.”

The instrument proposed by the Center for the Cassini mission does the same kind of atmospheric measurements as the one they will build for CRAF, but each instrument has a different design because they are going to different places, Dr. Heelis said.

“Cassini is a mission to Saturn,” said Dr. Heelis. “And it will orbit the planet and obtain detailed information about its moon, Titan. Our (Cassini in-strument) is principally designed to diagnose the atmosphere of Titan.”

Both missions will send out probes. According to a NASA report, CRAF will drive a probe into the comet’s nucleus, and Cassini will send an instrument probe into Titan’s atmosphere.

Despite many similarities, each mission is, of course, unique.

“The most interesting part of the CRAF mission is that the comet is the most primordial matter in the solar system, so that if we get a good look at that stuff, that’s what the rest of the solar system evolved from. We get ideas about the evolution of the planets by looking at the oldest matter in the solar system,” said Dr. Heelis.

The Cassini project to Saturn — a planet more primordial than Earth but less primordial than a comet — offers scientists a look at part of the evolutionary process of planets, according to NASA’s report on the projects.

Cassini, however, also “represents an opportunity to study a body that has a dense atmosphere and interacts with a magnetic field,” Dr. Heelis said. The Earth’s atmosphere, he said, interacts with the magnetic field of the sun, and Titan’s atmosphere interacts with Saturn’s magnetic field. Dr. Heelis said that Titan, unlike Earth, has no magnetic field of its own, but correlations can still be made.

Currently the Center analyzes data closer to home. Dr. Heelis said there are “spacecraft out there right now sending data to the ground and back to us for analysis concerned with the atmosphere of Earth.”

“Future EOS (earth observing system) missions are scheduled for 1996,” he said. “That’s a big mission to diagnose the environment of earth and man’s effect on it. It’s part of the global change initiative.”

Analyzing data gathered by other NASA space missions has been an ongoing activity at the Center for some time. NASA’s 1975 Viking mission to Mars and its 1978 Pioneer/Venus mission are two planetary missions UTD has been involved in, but now, according to Dr. Heelis, the data interpretation is mostly finished.

Much of the analysis is done by graduate students, and many of them go on to work for NASA at the Applied Physics Lab in Washington, D. C., Dr. Heelis said.

Because of the time element involved in many space projects, Dr. Heelis said the Center recruits at the high school level. As an example, he said the graduate student who will analyze data from Saturn and its moon Titan is now in elementary school.

Unwilling to allow any potential recruiting opportunity to slip by, he quickly added: “If there are any graduate students out there wanting to work in space physics, come see me. We’re doing lots of stuff right now.”

Leave a Reply