Thirty-four percent of college-aged students have felt depressed at least once in the past few months, according to a survey conducted by the Associated Press.

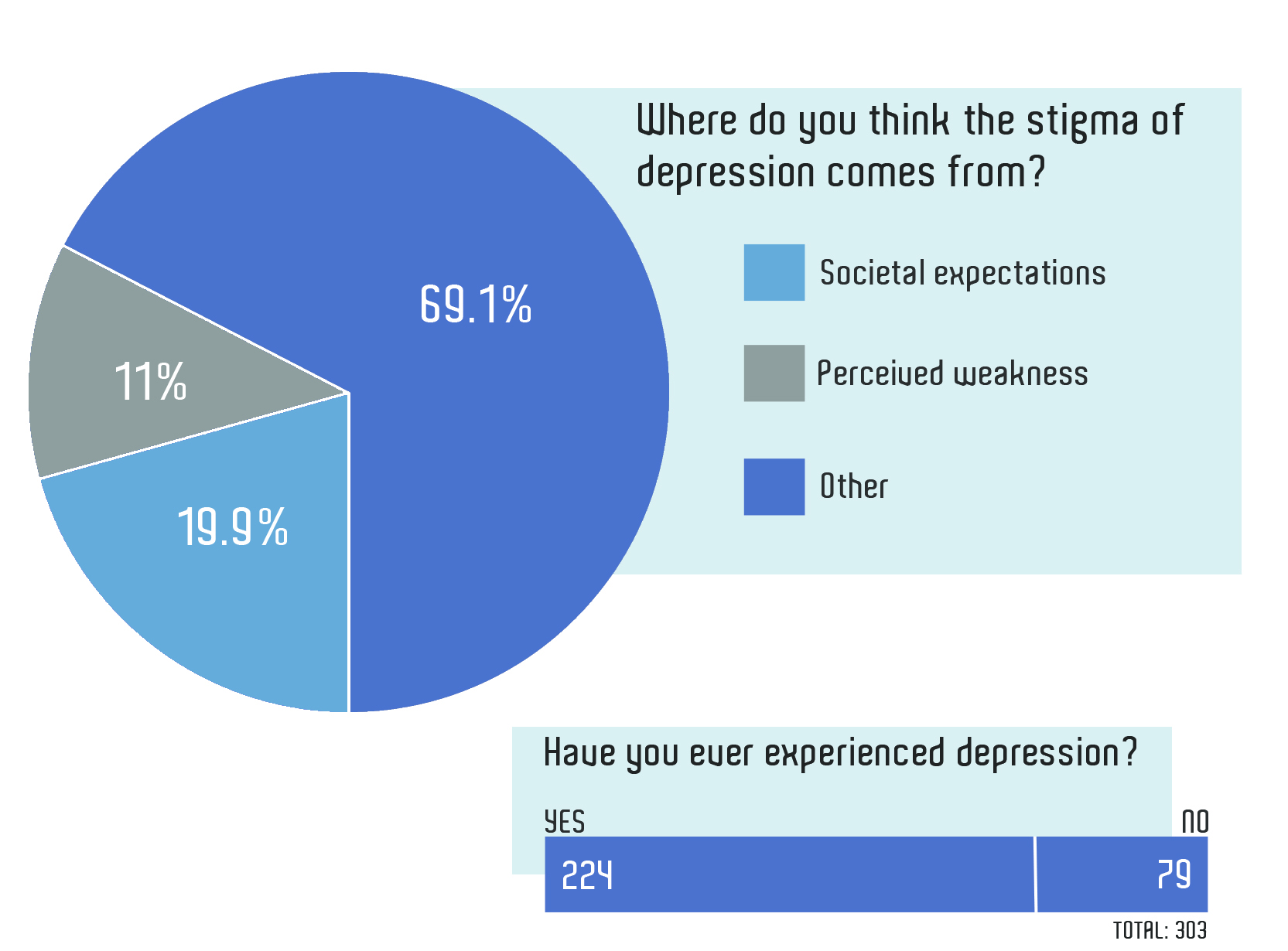

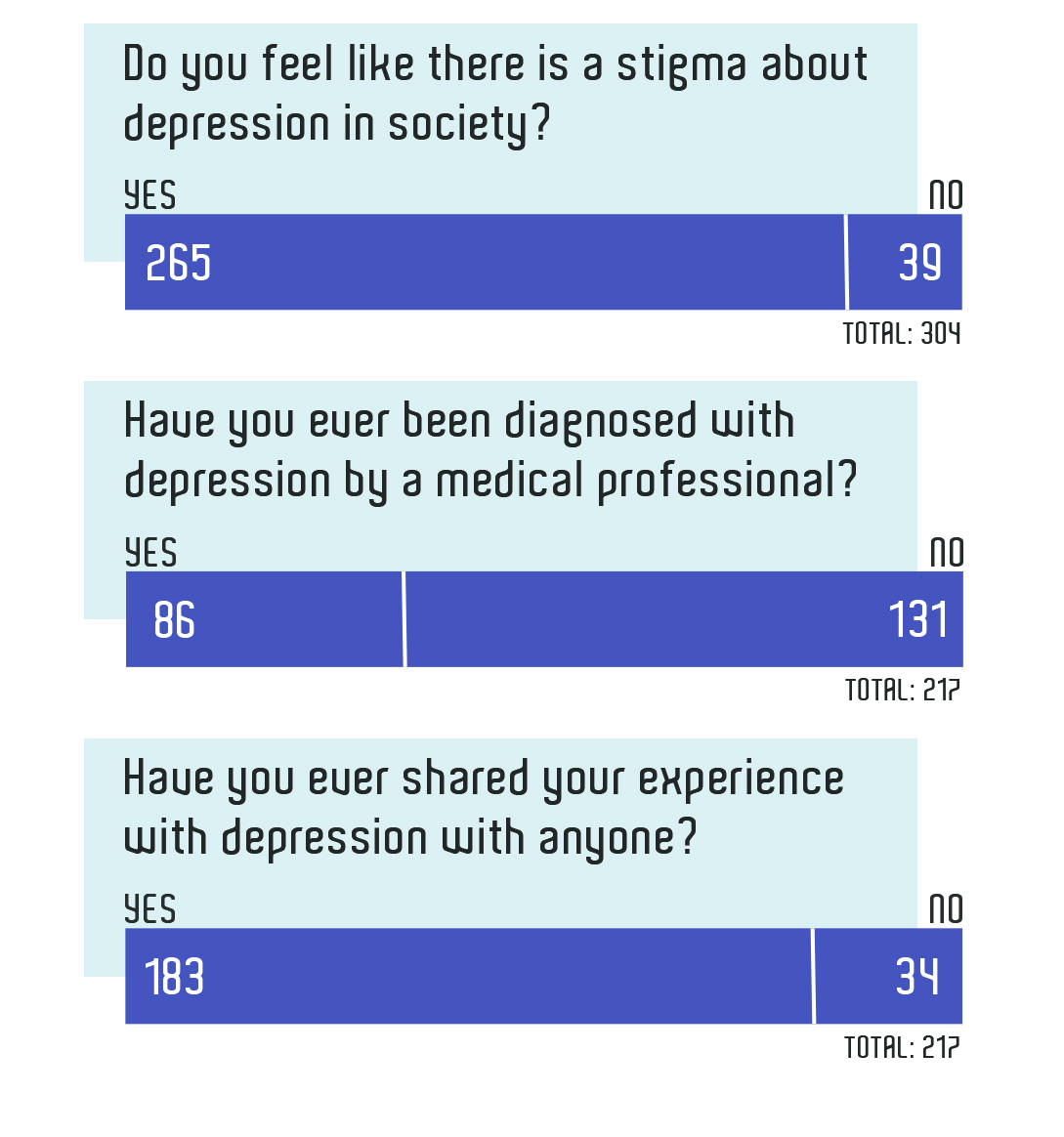

UTD fits into that national narrative regarding depression. In a survey conducted by The Mercury, out of 303 respondents, about 74 percent reported experiencing depression, and 40 percent of those who’ve experienced depression have been diagnosed by a medical professional.

Virginia Beam, an arts and performance senior, is one of the many students on campus with depression. She has shared her story with two other students who have struggled the way she does. Although each of them has a unique version of the disorder, they all agreed with Beam’s basic description.

“If I listened to my brain, where it’s saying ‘It’s too hard, it’s too much work, it’s not worth it,’ I would never go anywhere or do anything,” she said.

“That little bit of extra effort to do anything”: What does depression look like?

Beam, Mimi Newman and Caitlin Rogers have all been diagnosed with depression.

“I kind of describe it as Jenga,” Newman, an arts and performance junior said. “I’ve been carefully building up and building up and building up. And then I take one Jenga block out and the whole thing falls down. I almost feel like I’m starting all over again.”

Newman characterizes her depression as antithetical to Beam’s. Beam, a 26-year-old student, instead feels a constant, low-level version of the what the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual — a classification text for psychologists — considers a mental disorder.

“It’s less of peaks and valleys and more of a quiet hum in the background,” she said. “It’s always there, for about 15 years now. It’s kind of like walking in a pool, where everything is just a little bit harder and it takes that little bit of extra effort always to do anything.”

Rogers, a literary studies senior, recently experienced one of her depressive episodes after receiving her GRE scores. Following that disappointment and a negative critique from one of her professors, Rogers said she never wanted to go to school again.

“You just lay there and you sulk and you wallow, but you have to do that,” Rogers said. “If I had pushed it and I’d gone to class, it would’ve been way worse down the line.”

The three women — all non-traditional students — have formed a support system for one another and a bond over the past year. Newman, Beam and Rogers are quick to finish each other’s sentences and often find it easiest to define their depression by the similarities and differences in what they experience.

Beam and Rogers, for example, both have gotten so discouraged by their depression in the past that they’ve dropped out of all their classes, partially explaining why they are non-traditional students.

“One year I was hospitalized for a suicide attempt and it just threw everything off,” Beam said. “So it was like, ‘We’ll try again next semester.’”

Newman, on the other hand, describes herself as a “battle axe.” She’ll keep pushing through the “waves of sadness,” often using her studies as a distraction.

“I hide from my conditions in school,” she said. “Which isn’t necessarily good. … I put myself in this state where everything is resting on my schoolwork. My entire mental state is resting on this one random paper that is three percent of my grade. But it’s really important that I get an A because that’s going to change everything. And suddenly I find myself completely breaking down and having a mental breakdown.”

“I just felt normal”: Seeking Help

Beam has been on antidepressants since she was 14 years old.

“I hit on one where I realized one day (that) I feel normal. Not happy or high, but I just felt normal,” she said.

In the past, she’s tried several times to go off her medication. Eventually, her doctor convinced her to stop and allow herself to accept the help so that she can be there for her husband and two children.

“I have people who need me, and I owe it to them to take care of myself,” she said.

All three women have had to fight their tendency to isolate themselves from everyone when feeling depressed. Part of what makes reaching out difficult, Rogers said, is not knowing whether or not the response she gets will be helpful.

“I’d go seek out my mother and she’d say something like, ‘Oh, you’re fine. You’ll be better,’” she said. “That’s not what you want to hear. You want to (hear), ‘You’re right, that sucks. Let’s do something.’”

Newman feels lucky because the people she’s reached out to in the past have responded to her negative affects in constructive ways.

“My friend happened to respond in the exact way I needed it to,” Newman said. “Now I’m very careful about who I talk to, because if you get the wrong response from somebody, it can literally throw you back. And then you’re drowning again.”

“You don’t have to explain yourself”: Making Meaningful Connections

Now, with each other to turn to in times of stress, all three are less likely to seclude themselves.

Rogers remembers first meeting Newman when she sat down next to her in a class. Without pause, Newman began telling her a little bit about what she was going through, leading Rogers to feel comfortable enough to share her own struggles.

“Accepting the things that are a part of your life, like depression, and being able to communicate about it with other people makes them realize that it’s okay, too,” Rogers said.

Beam said she’s felt relief from interacting with other students, like Rogers and Newman, who are similar to her.

“I’ve met a lot of people who have similar stories,” she said. “It’s encouraging to be like, ‘I’m not the only one who’s not on the four-year plan and who can’t just power through it when things are tough.’”

Newman, Beam and Rogers are all uniquely able to understand what the others are going through, something Newman said has been extremely important.

“You don’t have to explain yourself anymore,” she said. “It’s really tiring to constantly come up with excuses as to why you are the way that you are when you had no choice.”

The Counseling Center

Although Newman, Rogers and Beam never employed the services of the psychologists on campus, the Student Counseling Center at UTD does offer services to students who are struggling.

Director Jim Cannici estimates last school year, the center saw between 5,000 and 6,000 students.

The center allots 12 free sessions for students per year. On average, a student will use about half of those, which is consistent with the national averages, Cannici said.

The most common problems people present to counselors at the center are anxiety, depression, academic problems and relationship problems.

“Some of those relate to one another,” Cannici said. “For example, if there’s a break-up in a relationship, often that will lead to anxiety or depression.”

A major issue Cannici sees students face, however, has to do with the transition from high school to college.

“It’s such a huge change for people to go from high school, where people had a certain group of friends and things were taken care of by family, … and to be more independent at the college level for those that live away from home can be a real challenge,” he said. “And for a lot of students, having all that independence is too much for them.”

That transition, Cannici said, contributes to the high prevalence of depression in college-aged students.

“There’re so many challenges to being a young adult,” he said. “It involves choosing a career, making new friends, figuring out how to fit into a new environment. … And there are a lot of disappointments that occur. We get a lot of students here who were towards the top of their class in high school and they come here and all of a sudden, classes can be very hard, they’re getting B’s, they’re getting C’s. They start to doubt themselves.”

As for solutions for that depression, Cannici strongly recommends counseling, despite any stigma that might exist about getting help.

“There’s a history of people who, understandably, may want to be more private about seeking mental health services,” he said. “Here’s the challenge I think: a lot of things are bunched together. We have severe mental illness on one side, and then we have what are sometimes called problems of living or adjustment problems. We see the entire gamut here. Mostly people don’t want to be called mentally ill. Everybody in the world has adjustment problems from time to time in their life. But they don’t want to be associated with (the mentally ill), but they’re all put in the same bag of mental health. … I think that’s changed over the years and the stigma is getting less and less.”

“It’s easy for you to judge”: Fighting the Stigma

Alan-Michael Sonuyi co-founded a chapter of the national non-profit organization Active Minds on campus this fall. The club seeks to spread understanding about mental health and reduce the stigma associated with mental illness.

“I know someone who has suffered from mental illness. I know someone who’s contemplated suicide before,” Sonuyi, a neuroscience sophomore, said. “I feel that a lot of the people who go through mental illness are afraid to say anything. I feel like that’s a group (whose) voices aren’t heard and we as a community should try to stand up for them.”

Active Minds raises awareness on campus about the resources available to students who are struggling — namely, the Student Counseling Center, the Student Wellness Center and the Center for Students in Recovery.

Beam, with her personal experience with depression, said she has experienced the very stigma that Active Minds aims to erase.

“People are uncomfortable with things they can’t fix,” she said. “It’s hard to be around someone consistently and not be able to fix them and just to be in it with them. It’s hard. And I don’t blame anybody for feeling that way.”

Eighty-seven percent of respondents in ***The Mercury’s*** survey said they believe there is a stigma about depression in society. Active Minds focuses on the negativity around that stigma.

“A lot of people aren’t comfortable with things that are different than themselves. It’s easy for you to judge people with mental illness without having experienced it yourself,” Sonuyi said. “We at Active Minds want to change that.”

Leave a Reply