The Erik Jonsson School of Engineering and Computer Science, or ECS, is one of UTD’s largest and most well-known academic schools, ranked No. 4 in Texas for engineering by The College Pod. However, in recent years, ECS has grappled with problems resulting from unprecedented surges in undergraduate enrollment and budget constraints.

Students who feel the school isn’t meeting their needs have mentioned a range of complaints. The Mercury polled students on their experiences with ECS advisors and found that out of a sample size of 97 students, 49% said a typical advisor response time was a couple of weeks, and 22% said a couple months. 30% of respondents said they had been assigned four or more advisors during their time in ECS.

“Advising has this terrible pattern of having people just [go] completely missing, having advisors not doing their job when they respond, and that’s affected me and a whole bunch of students every registration cycle,” computer science junior Jocelyn Heckenkamp said.

When asked to rate how satisfied they were with their advising experience on a scale from zero to 10, 36% of students gave their experience a zero out of 10, with only one respondent giving a 10 out of 10.

In a Jan. 23 interview with The Mercury, ECS Dean Stephanie G. Adams, who considers herself a “student-centered dean,” addressed some of these concerns.

“There’s a perfect storm happening,” Adams said.

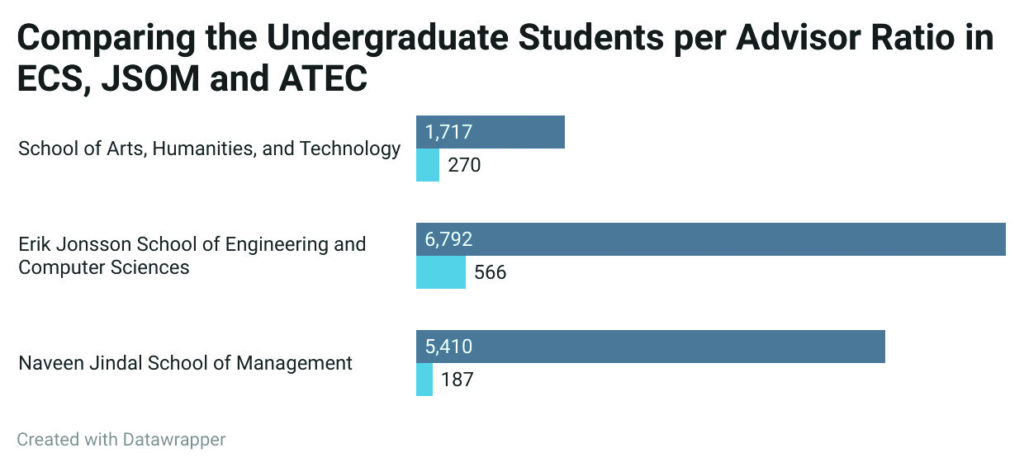

Between 2008 and 2021, ECS grew by 6,027 students, which makes it a third of UTD’s undergraduate population based on numbers from The American Society for Engineering Education. As of February 2023, ECS has 6,792 undergraduates, with a student-to-advisor ratio of 566:1. The National Academic Advising Association, or NACADA, recommends an average caseload of 296:1. According to Adams, four-year public colleges should aim for 260:1.

For comparison, in fall 2021, UT Arlington’s College of Engineering had an undergraduate student-to-advisor ratio of 260:1 for a population of 5,201, according to Joe Carpenter, UTA’s chief communications officer. Within UTD, ECS has the highest undergraduate student-to-advisor ratio, based on data from Administrative Project Coordinator Vanessa Balderrama.

When Adams became ECS dean in August 2019, the school had only 12 advisors and two assistant directors of advising, compared to the 23 advisors they would need to meet NACADA’s 296:1 recommended ratio. At the time of the interview, ECS had only 11 permanent advisors and two temporary advisors.

“I’ve been trying every chance I get to add more advisors,” Adams said. “There’s gonna be more complaints if you have more students.”

Mechanical engineering senior Kyle Settelmaier is an ECS student who said he had trouble communicating with advisors when he wanted to change his major from mathematics to mechanical engineering as a junior.

“[It] was a bit of a nightmare, and nobody was able to help,” Settelmaier said.

Settelmaier said he narrowly missed enrolling in a crucial prerequisite course when his degree plan had not been updated. By the time the advisor responded to his concerns over email, the class was full. Had it not been for a last-minute dropout, Settelmaier said he might have had to stay at UTD for another semester.

Four survey respondents said that the actions or inactions of their advisors prevented them from enrolling in a class, as well as two survey respondents who said they were forced to delay their graduation and spend another semester at UTD.

“It’s not the end of the world, but that’s [potentially] money down the drain for no reason,” Settelmaier said. Beyond the pandemic and natural turnover, external factors have compounded the rate at which advisors are leaving UTD. Adams said that advisors have taken similar positions at other schools with lower caseloads. Since the January interview, Adams said that ECS had lost another advisor.

Dallas College was one of the institutions Adams mentioned, as they pay their entry-level “success coaches” $65,000. For comparison, according to UTD’s open payroll, two ECS academic advisors have a salary of $41,989 and $49,693. The Mercury reached out to success coaches at Dallas College who were previously ECS advisors but received no affirmative responses.

“If you can make the same money and go to another unit with less students, some people are doing that,” Adams said. “That’s not something I can control.”

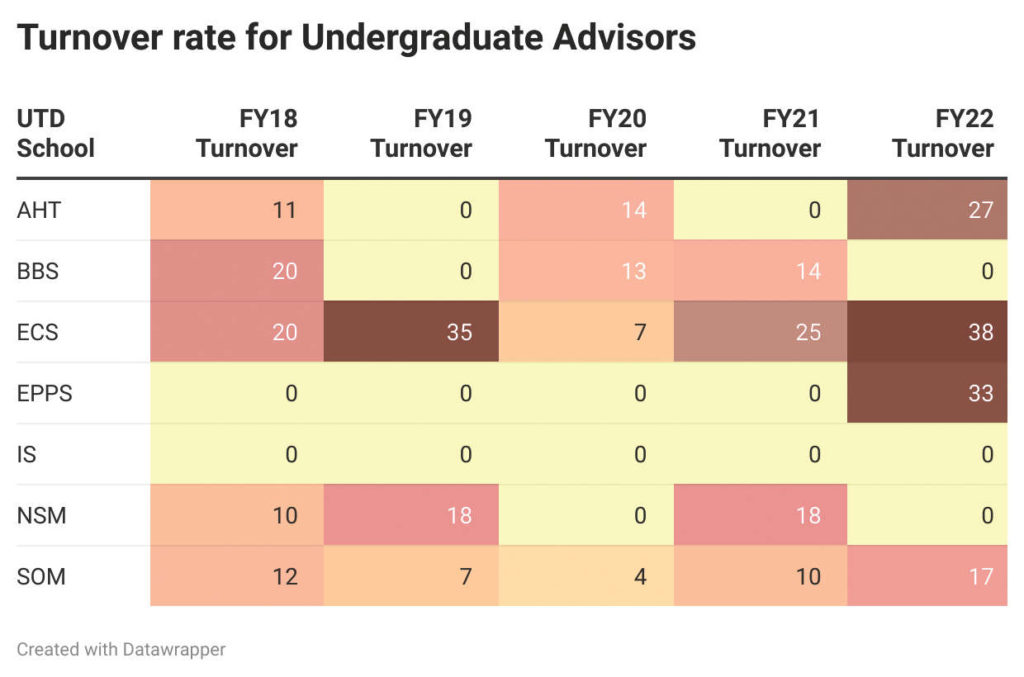

Data from a FOIA request revealed that ECS had the highest undergraduate advisor turnover rate — the rate at which advisors leave a department — at an annual average of 25% in the last five years. In 2022, ECS had a 37.5% turnover rate, the highest of all UTD schools. The School of Economic, Political and Policy Sciences was the second highest that year at 33% but had zero turnover in prior years.

Neuroscience senior Grant Feuerbacher said that advising was one of the reasons he left his original major of biomedical engineering. Feuerbacher came to UTD for its engineering program, however, during his first semester in spring 2022, Feuerbacher said that he waited two weeks for advisors to respond to his emails about an erroneous hold on his account. Feuerbacher said it took four months to hear from advisors about withdrawing from his classes due to medical complications with a family member.

“I would say advising is one of the most important resources students have to help ensure their success, and we don’t have that here,” Feuerbacher said. “Their solution to a problem they created is to put the burden on the students. And it’s our fault they aren’t doing their jobs and responding properly?”

Feuerbacher said he doesn’t blame anyone specifically but describes some emails he received as “dismissive” and “condescending.”

“It’s been nothing but the most stressful year of my life,” Feuerbacher said. “I regret ever coming here.”

Heckenkamp said that after not receiving an email response for the entire summer, she had to walk into the advising office to get registered for classes in fall 2022.

Adams has tried several strategies to mitigate the school’s turnover rate, including hiring psychologists for faculty and students, sending new hires to NACADA training seminars, increasing bonuses and allowing more overtime work opportunities.

Still, Adams said that advisors’ job duties go beyond helping students pick classes. They are tasked with managing student orientations, retention rates and career development. Advising is a small but crucial part of their job. Unfortunately, Adams acknowledges, it is “the most broken part.”

Nevertheless, Adams believes students need to take responsibility for themselves.

“Part of the college experience is to prepare you to function as an independent citizen down the road,” Adams said. “We want to empower students to have some ownership in their own planning and execution, but if students don’t read their emails, that’s where we get into some problems.”

Adams said that the school’s early enrollment numbers showed less than 30% of students opened their emails from advisors.

“[Advisors are] sending out emails telling you how to get the information and where to find certain things that you should be able to do on your own,” Adams said. “When we do our due diligence, we find no evidence the student has written to anybody.”

Heckenkamp said that many students care too much about what classes they are in to not look at their emails.

“When there’s things that I need to get done, I’m checking my email every day,” Heckenkamp said.

Willie Chalmers III, an ECS student council speaker and computer science senior, said he sees both sides of the issue. Chalmers hosted “Donuts with the Dean” and other events in recent months with the goal of communicating with admin about the advising problem. Chalmers said that he felt for ECS and their struggle to hire staff.

“From what I’ve heard from talking to other students and from my personal experiences, [the issue is] response times, and occasionally the information students receive is inaccurate,” Chalmers said. “The reason they have to answer so many emails in the first place, or just request in general, is because there aren’t enough people.”

Like Adams, Chalmers believes students could do more to help themselves.

“Frankly, Comets don’t read,” Chalmers said. “There’s a sizable portion of students who just want someone else to do the hard work for them … a lot of the issues [are] just students not putting enough initiative to plan their own coursework.”

ECS has several policies in the works to address the advising problem, including peer advising, where upperclassmen could receive course credit or money for helping younger students plan their degree path. Other solutions include a direct text line between students and advisors as well as suspending ECS 1100, usually taught by advisors, so they can allocate more time to tend to student needs.

“I’ve gotten more sympathetic to the school’s situation for advising,” Chalmers said. “Trust me, they are aware of the problem.”

Leave a Reply