The Office of Parking and Transportation, responsible for the sale and pricing of parking permits, has a budget that students and faculty members have tried and failed to obtain. In the absence of this data, students and faculty alike have voiced concern over increasing permit prices, a lack of lower-tier spots and accusations of artificially inflated demand for high-tier parking.

ATEC senior Alex Garza said he’s noticed a steady increase in permit costs since he came to UTD. Garza worked in the Office of Parking and Transportation last semester as a student worker.

“My understanding is that the parking permit is to pay for the maintenance of the parking lots,” Garza said. “I just don’t think that those (operating) costs justify the price that we pay for permits, especially as a commuter school.”

Terry Pankratz, vice president for budget and finance, said that at UTD, permit prices are competitive with other universities in the area, but said that the budget structure itself isn’t quite comparable because much of UTD’s parking infrastructure is new and hasn’t been fully paid off yet.

“A price increase (for permits) might be in anticipation of this debt that’s coming,” Pankratz said.

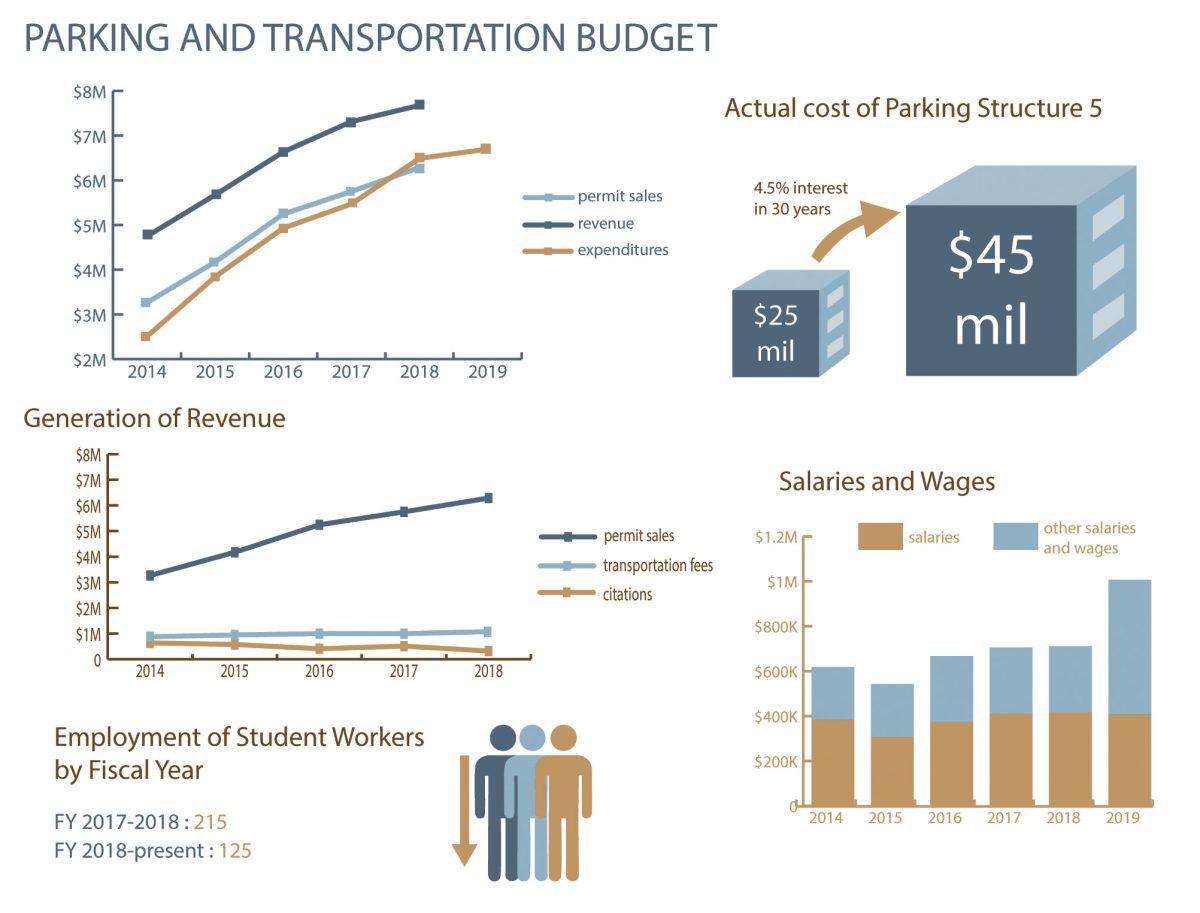

In order to fund new parking garages, the university takes on debt in the form of bonds, which are paid off over 30 years at a 4.5 percent interest rate. Construction costs for the next parking structure are estimated at $25 million, Pankratz said. Paid off over 30 years, the total cost will be $45 million.

Funding for the Office of Parking and Transportation, including the debt service, is generated primarily by permit sales.

Pankratz said that in order to get approval for the budget, Parking and Transportation officials must demonstrate that they can generate income that is equal to the debt payment for that year, plus a 10 percent excess to cover other expenses.

According to parking budget documents obtained from the Office of Budget and Finance, revenue from permit sales alone far exceeds that 10 percent figure. Permit sales have consistently been at least twice the amount of the debt service payment for the last five years.

Income from permit sales is so high, in fact, that for the last four years, the revenue gained from sales alone could pay for the entire operating budget of the Office of Parking and Transportation.

It was only in fiscal year 2018 that operational expenses exceeded permit revenue — but only by 3 percent. When other revenue streams were factored in, all expenditures were covered, with $1.07 million to spare.

The Office of Parking and Transportation also generates revenue via citation fines and a transportation fee that students pay as part of their tuition.

While the number of citations has gone down, the average price per citation has increased by about $25 over the past five years.

Budget and Finance officials said that there likely won’t be any increase in permit prices next year, but that could change as the budget is sent to the Board of Regents for approval.

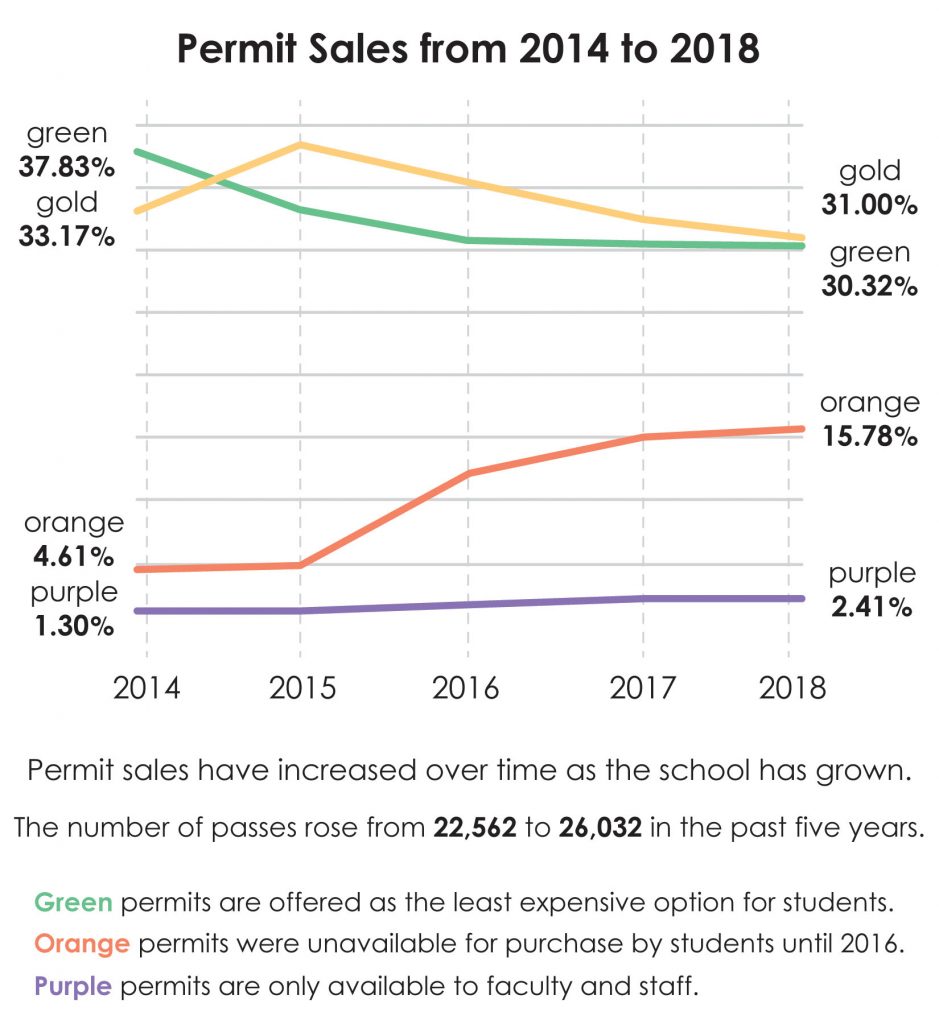

Parking permits are priced on a tiered model: a green permit, at $140 per year, is the cheapest. Gold permits are $250, orange permits are $385 and purple permits are $595 and can only be purchased by faculty and staff. Each permit is priced at an average of 50 percent greater than the tier below.

Garza said that one of the most common complaints among students is the availability of spots for lower-tier parking permits.

According to data obtained from the Office of Parking and Transportation, the sale of green permits has declined every year since 2014, even as the university’s enrollment grew. In 2015, gold permits overtook green as the most common permit sold. Sales of the two most expensive permits, orange and purple, have increased steadily and outpaced the growth in total permit sales.

Melissa Wyder is the vice president of the Staff Council and a long-time member of the university-wide Committee on Parking and Transportation. Wyder said she was told that restriping is based on sales from the previous year, as well as the location of faculty and staff offices.

“If everyone in, say, the Physics building wanted to buy purple (permits), then the parking garage next door would get a lot more purple (spots) the next year,” Wyder said.

She said she wasn’t sure if anything was being done to assess student demand for spots. Officials from Parking and Transportation could not be reached for comment despite multiple attempts.

Another member of the Committee on Parking and Transportation, JSOM professor Judd Bradbury, said that faculty and staff also had concerns. He said some members of the committee suspected the office might be trying to artificially inflate demand for more expensive permits. Before 2016, gold was the most expensive permit available for students to buy.

“There were some faculty members who were concerned when orange permits were opened up to students,” Bradbury said. “Some were suspicious it was a scheme to raise pricing and demand for the more expensive purple permits.”

Wyder said that she’s long had trouble obtaining budget data from the office, despite her position on the committee.

Fiscal year 2019 will see a 104 percent increase in the budget line item “other salaries and wages,” which Pankratz said likely includes student worker wages and wages for temporary contract workers, but could include other costs.

Student workers within the Office of Parking and Transportation did not report any across the board wage increases. According to figures from the Career Center, hiring numbers for student workers at the Office of Parking and Transportation have declined from last fiscal year.

It is possible that the large increase in this budget item is due to an accounting coding error. Orkun Toros, assistant vice president of budget and resource planning, said that a similar error occurred in 2015, which resulted in a 408 percent increase in budgeted employee benefits.

“They accidentally put $90,000 under their benefits and no one caught it,” Toros said. “But it seems like they generated enough revenue that year to cover it anyway.”

Toros said it’s typical for revenue-funded offices to have control over individual budget line items like benefits and wages, and once the budget gets to the Office of Budget and Finance, they’re only looking at the bigger picture.

“We just look at the bottom line — revenue, expenses, most significant changes and then they’re good to go,” Toros said.