Sergeant Mike Rials felt as though he had lost purpose in life. He had burned several bridges with his friends and family and spent most of his time indoors.

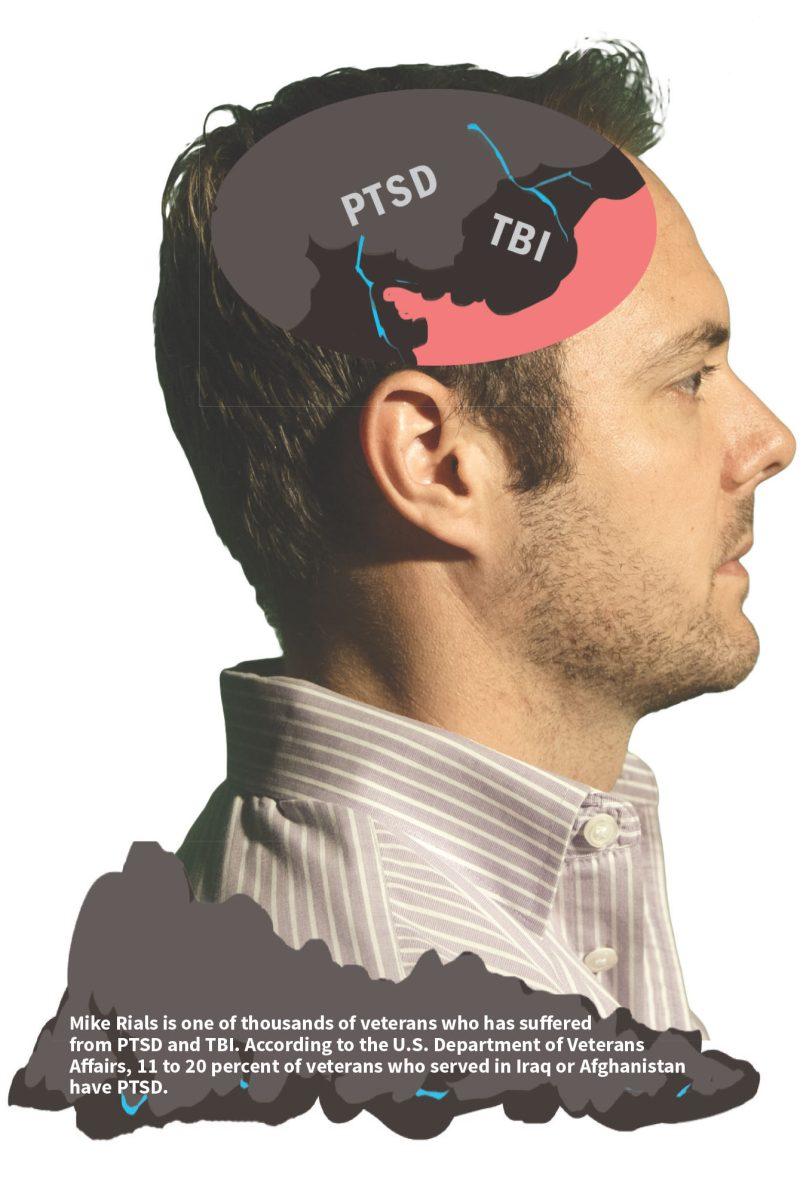

On his third deployment to Afghanistan with the Marine Corps, Rials was caught in a blast when a vehicle hit an anti-tank mine. Along with losing a friend in the explosion, he suffered severe burns and was diagnosed with traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder.

After the attack, life just didn’t feel the same.

“A month and a half after my injury, I was back home out of the Marine Corps on terminal leave and really didn’t have a direction or purpose,” Rials said. “I was somewhat lost or ill equipped to handle a transition at the time.”

His biological father took his own life when Rials was five years old and his stepfather had recently lost his life to pain pills. In the absence of both of his mentors, Rials became mentally unstable.

He enrolled at UT Dallas to find direction in his life and gradually weaned himself off of self-medication.

“I still wasn’t doing too good,” Rials said. “My thoughts were very jumbled, very disorganized. I didn’t see myself communicating very well. I still had a lot of ruminating thoughts and still dealt with a lot of emotions. I felt numb.”

To counter this, Rials looked for a cause to join. He became highly involved in veterans’ affairs and became a part of a student veteran organization. At an event held on Veteran’s Day in 2011, Rials signed up for a PTSD study conducted by the Center for Brain Health.

It proved to be a life-changing choice.

“I tried something else out for the first time and kind of swallowed my pride,” Rials said. “I wanted to improve. I (wanted) better and (didn’t want to) feel sorry for myself. It was the best decision I’ve made for quite some time.”

Problems with PTSD

Post-traumatic stress disorder is a neurobiological phenomena exhibited by someone who is exposed to chronic threat, horror, the possibility of severe injury or death. Tina Bass, a clinician and research assistant at the Center for Brain Health, explained that the condition is like constantly having the flight-or-fight response active.

“It can be thought of as having your stress response stuck in the ‘on’ position,” Bass said.

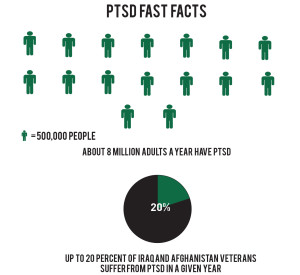

According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 11 to 20 percent of veterans who served in Iraq or Afghanistan have PTSD. Bass said PTSD results in impairment in occupational and social functioning, although every individual diagnosed exhibits unique symptoms.

Some of the common misconceptions about people who suffer from PTSD are that they may be more aggressive or that they may suffer from a character flaw. Bass said the center’s goal is to do away with these misconceptions and create long-term treatments for patients.

“That’s our hope; that the research will translate into clinical services and that these (services) will be adopted by anyone who treats individuals with PTSD,” Bass said.

One of the ways the center does this is through cognitive processing therapy, a treatment that limits PTSD symptoms. A study started in 2010 is trying to see if CPT can be enhanced with different forms of neuro-stimulation.

A main focus of the procedures at the center is the decay of traumatic memories. One type of treatment — the repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation — can lower PTSD symptoms by inhibiting the area of the brain that is responsible for violent reactions, hyper arousal and anxiety. The center is also testing high-definition transcranial direct current stimulation to see if it is more effective in improving quality of life.

The results of the study showed that PTSD symptoms dropped by approximately 50 percent. After participating in the protocol, Rials observed a significant change in his lifestyle.

“Now, instead of living in a small little bubble, I want to taste every new food, I want to try every new experience (and) public places don’t bother me,” Rials said. “I truly try to practice the tools that were given to me (at the Center for Brain Health).”

The treatments are unique because they are personalized forms of care that move away from medication based therapy, Bass said. She explained that individuals aren’t always compliant with prescribed medicine, so the center’s strategies could be another option for patients.

“Brain stimulation is using your own endogenous neurochemicals to change things at a neuronal level, as opposed to taking medication to make different changes,” Bass said. “(It is) enhancing the performance of or kick-starting those built-in systems.”

The head of community programs for the center, Molly Keebler, said veterans learn cognitive control in a brain training program called Strategic Memory Advanced Reasoning Training, or SMART, offered at the center. There are currently 20 veterans who participate in the program.

“We’re interested in how the brain changes,” Keebler said. “We’re interested in helping people change their lives for the better.”

Tackling TBI

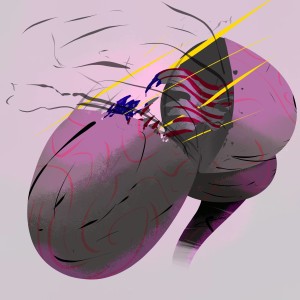

Traumatic brain injury, which usually occurs when someone suffers a violent blow to the head, can affect the way the entire brain works. After a traumatic brain injury, it is harder to block out irrelevant information.

The training programs at the center teach individuals who have TBI to organize and prioritize information and transform it into something of meaning. The center also teaches techniques to improve creativity and innovation.

Rials pointed out that research has proven how the brain was meant to operate. With the strategies taught to the patients, they are able to train their brains to work in the proper way.

“My communication has become much more effective,” Rials said. “My confidence is up to where it was in the military. I feel more energized and efficient. I’m not so discombobulated anymore or all over the place. I sleep better.”

SMART is the only program of its kind in the United States and stresses affordable platforms such as Skype so that veterans are empowered to go through the program in their homes. Keebler said that the center hopes to acquire more funding to include group training.

Moving forward

When veterans go through rehabilitation programs, their insurance stops payment if the individual has plateaued against a certain standard that measures progress. Keebler said their programs focus on constant development rather than reaching a stopping point.

For Rials, global education on brain health is vital to combating the stigma against mental illness.

“There is a lack of education and there’s a lack of understanding of how the brain is wired to work, what’s good for the brain, what’s bad for the brain and how much control we actually have of the brain,” Rials said.

He said that going through the programs at the center has helped him readjust and educate himself about brain health.

He is now in charge of the training programs offered at the Center for Brain Health that are based on in-house research. He said that being able to improve people’s lives has helped him regain his confidence as a leader and live a purposeful life.

“When I was in the military, I led anywhere between 12 to 43 men, and I’d like to say that those guys would follow me anywhere, and I get that same sense of feeling now,” Rials said. “I get to lead guys in a new phase in their lives. I get to train them to use their greatest asset: their brain.”