Neuroscience professor at Rosalind Franklin University highlights misinterpreted differences in feminine, masculine roles in society

As the little sister of three brothers, author Lise Eliot spent her childhood absorbed in Lincoln logs, Legos and cars – not necessarily the traditional girls’ pastime.

Eliot said she wonders if that made her more interested in math and science, which research shows is an effect of growing up with an older brother or if she was just hardwired this way like common scientific beliefs indicate.

This thought sparked her interest in gender difference and led her to write her latest book, “Pink Brain, Blue Brain,” where she debunks the worldwide view, saying it is misinterpreted and oversold.

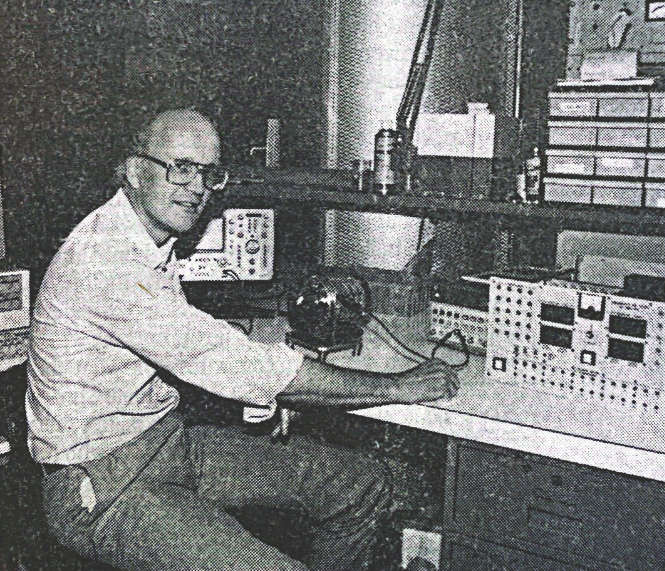

Eliot, now a professor of neuroscience at the Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science and author of two books and over 60 published works, spoke at the Jonsson Performance Hall as part of the Center for Values in Medicine, Science and Technology’s lecture series on Jan. 29.

“Gender difference is always a sexy topic,” Eliot said. “I discovered that a lot of the stuff in these books was based on one study that was chosen because it confirms stereotypes not because it was representative of the field as a whole.”

Director Matthew Brown and associate director Magdalena Grohman of the Center for Values in Medicine, Science and Technology organized the event.

“Dr. Eliot isn’t denying the differences, but she’s pointing out that they’re different than we’d like to think,” Grohman said. “They’re blown out of proportion.”

From the first moments of birth, parents and even trained nurses talk differently about their sons and daughters, Eliot said. A video revealed a highly trained nurse giving the Apgar test, a test that measures how healthy a baby is one minute after birth.

Eliot noticed if the baby was a girl, the nurse would often comment on the one-minute-old baby’s beauty but if the baby was a boy, the comments revolved around his intelligence and size.

“We set up this status hierarchy at an age where there’s no physical difference in size between boys and girls,” Eliot said. “They really don’t change until after puberty.”

Gender identity solidifies at around three years of age, when children become active agents of their own gender divergence.

However, the scale of the differences isn’t as large as most may believe. There are the clear-cut differences such as men having larger brains than women and boys having larger brains than girls. Boys are 10 percent larger than girls, both physically and in brain size throughout their life cycles.

Another proven difference is that girls mature more quickly than boys, as a result of hitting puberty one to two years earlier.

Similarly, the brain development finishes one to two years earlier as well. That explains school performance in the eighth grade where the gender gap is most evidently seen.

Aside from those two big differences, there is no clear research that links to the behavioral differences, despite what prior studies may lead one to assume, Eliot said.

Brown said it’s important for people going into these fields to have an awareness of the issues that arise and to think of themselves as decision makers in research and design that will have a social impact.

“That’s nothing special in technology and science. That’s just ordinary ethics,” he said.

One of the other differences between girls and boys is in spatial skills; the difference arises at age four or five, and grows larger throughout the years because boys play more with blocks, video games and other targeted visual spatial games.

The classic test is a mental rotation, where a person is shown three-dimensional blocks and must decide which block is the same one rotated. Men outperformed women in this task, Eliot said.

“Believe it or not, toys have stronger gender labels now than when they did in the ‘70s and ‘80s,” Eliot said. “When Legos were first developed, they had no gender to them at all. They were just primary colored blocks for boys and for girls.”

But as different themes began to associate with the Legos like Star Wars, 80 to 90 percent of Legos were purchased for boys.

“That’s a huge lost opportunity for girls especially when you have those two-dimensional construction sets you use to build a three-dimensional object,” Eliot said. “That’s exactly the spatial visualization that’s important for architecture, engineering and lots of mechanical skills.”

However, Eliot admits that developing research on children is difficult. Eliot said her main challenge in writing “Pink Brain, Blue Brain” came when she decided to completely flip her thesis half way through. Originally, it was a book for parents about their sons and daughters and portraying how they are different in their behavior and in their brains.

“I didn’t realize how bad the evidence on sex differences were,” Eliot said. ”I remember the ah-ha moment when I realized that my book was going to be about debunking, not selling.”

As a mother of two sons and a daughter, Eliot is incorporating her values in her personal life.

“When kids become teenagers, they don’t like to listen to their parents much, so all my nagging about their brain development probably started to backfire,” Eliot said. “They understand that males and females have absolute equal potential in the world and what you do with your time is going to determine what your brain is good at. I like to think that their attitudes are more open-minded.”