A razor slices across an eyeball. Thin clouds move through the moon; jellied insides spilling out of a lamb’s eye. When the world needed weird movies most — they disappeared.

“Un Chien Andalou” has a striking opening scene that heralds an infinitely more confusing short film. Co-created by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, painter of the iconic melting clocks, “Un Chien Andalou” is a warm favorite of a brand of cinephile who’ll claim “you don’t get it!” when you are confused about a five-hour indie film that claims to be about famine but instead shows only a rustling paper bag with cuts to a screaming woman woven throughout. Even after a century since its 1929 release, the narrative of “Un Chien Andalou” is incomprehensible; perhaps even more so because of the established film grammar that we have grown up in and understand intuitively. The half-hour film is full of nonsensical plots only loosely tied together through the same actors in scenes. It’s tense, for reasons we can’t understand. It calls upon its viewer to create their own meaning, to abandon superficiality and discover what recent movies have been failing to deliver: a sense of imagination and wonder.

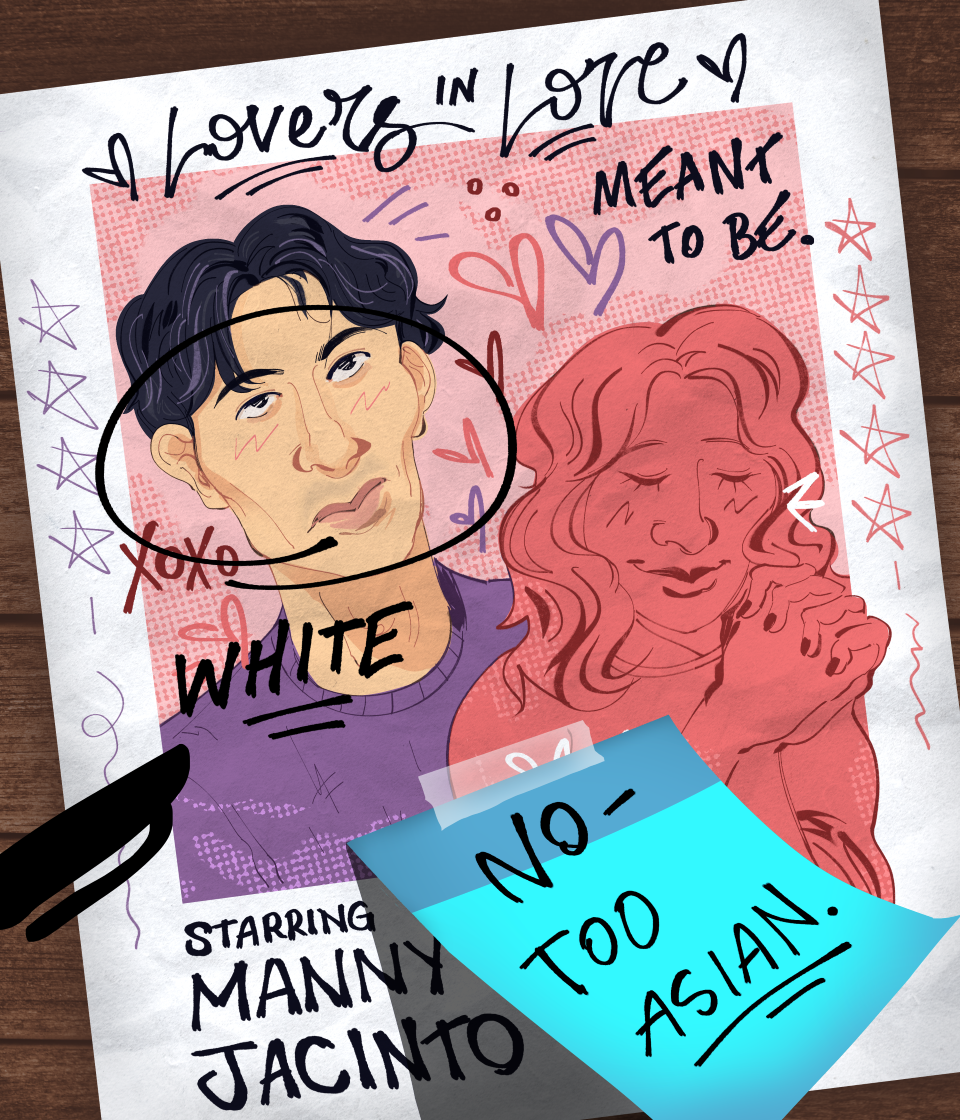

Movies today are largely adaptations of novels, like “It Ends With Us” or other intellectual properties like games, such as “Borderlands,”, sequels like “Inside Out 2” or remakes like “Mean Girls.” When original films are few and far between, riffing off existing media guarantees an audiences’ time spent will at least be mildly entertaining. Original films often suffer from cheesy dialogue and uninspired romance, making sequels all the more appealing. Within Hollywood’s recent memory, only a few wide-release films have been given free rein, like “Everything Everywhere All At Once,” “The Green Knight” and “Poor Things.” But not all hope is lost — production company A24 has excelled in facilitating and marketing arthouse-style films in the cultural zeitgeist, and Emma Stone’s win of a 2024 Academy Award is a potential sign for a resurgence in esoteric cinema.

“Poor Things” by Yorgos Lanthimos is a thrilling 2 hours and 21 minutes, consistently keeping the viewer on their toes through ridiculous shots and outrageous dialogue, following Emma Stone’s Frankensteinian character, Bella Baxter, as she discovers freedom of her body and mind, sex work, socialism, cruise ship horrors and the secrets behind turning men into goats. Bella’s naïveté allows her to challenge norms that many of us have accepted as tragic facts of life — for instance, the stigmatization of sex work, labor abuses, misogyny — while it fools the men around her into thinking they can control her. “Poor Things” may be controversial, but it’s provided us a much-needed opportunity to discuss the portrayal of varying sexual appetites, the wondrous experience of being human and whether fish-eye lens shots actually serve the narrative.

Arguably, though sex is steeped within “Poor Things,” it’s not a sexy movie. “Challengers,” directed by Luca Guadagnino, definitely is. The movie starts with a tennis rally, tense and tightly paced, setting up the love triangle within the first few minutes. Zendaya’s character Tashi Donaldson is in control, dangling herself like bait in front of her husband Art, played by Mike Faist, and ex-boyfriend Patrick, played by Josh O’Connor, to get them to play a “good fucking game of tennis.” Guadagnino is a master of attraction on camera, and “Challengers” hurtles through a decade and change of the nastiest, most codependent love triangle known to cinema. The film’s conclusion is left intentionally vague, just barely resolving loose ends but creating, in a sense, the loosest end of them all by suggesting that Tashi, Art and Patrick can reconcile. In an interview with TODAY, Guadagnino wryly suggested the final collision of all three characters was a return to their roots: “They go back to the hotel room.”

Weird movies are essential to society. As capitalism tramples over artistic pursuits, like the acquisition, and subsequent dismantling of Blue Sky by Disney, movies that challenge the norm become only more necessary. Tropes we take for granted, like every action movie needing a villain, are upended by films like “Everything Everywhere All At Once.” “Everything Everywhere All At Once” oozes personality, its visual effects bringing back the magic of physical VFX on sets. It’s an action film with no villain, the greatest transgression of its genre: the big bad turns out to be the intangible concept of generational trauma. The love of filmmaking is evident in every scene; A necessary reminder, in the middle of Marvel movie #58 and Disney #261, of why we want to visit the cinema. It is not to see yet another talking animal making vague allegories toward discrimination, but to challenge our perceptions of the world and watch art that makes us light up inside. “Everything Everywhere All At Once,” “Challengers,” “Poor Things” and other films within this realm of oddities ask us all to be a little weirder.