Students deal with delayed signals, steep prices, strict regulations in attempt to find a place to live both on, off campus

There are more than 4,500 spaces to live on campus. Yet, every year, the race to be an on-campus resident seems to get a little bit harder.

UTD’s Residential Life is charged with the task of accommodating as many students as possible in a floor-plan of their choice and keeping the student body happy about this process at the same time.

Of the 4,700 spaces on campus, 2,200 are in the residence halls. Almost 80 percent of students in these rooms are freshmen, although currently Residence Hall North currently houses upperclassmen. Still, there’s a good majority of freshmen that want to move into the apartments in their sophomore year.

“More freshmen tend to (apply for) apartment applications a year or two later and our continuing growth with transfer and graduate students increases our demand for housing as well,” said Kevin Kwiatkowski, director of housing operations at UTD.

Then there are students like Alexander Kujak, a healthcare studies junior, who has wanted to move on campus for two years but hasn’t been offered a lease.

When Kujak, a transgender student, applied as a freshman, he was assigned to room with girls. He didn’t want that, so he decided to live off campus.

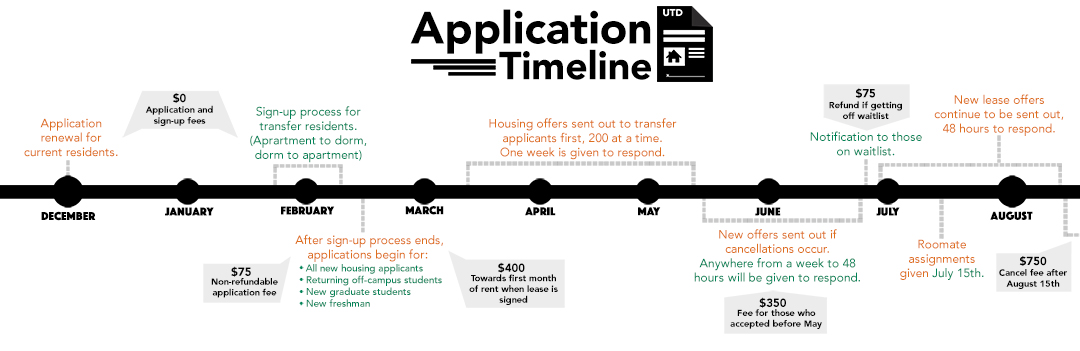

In order to get a legal name change, he wanted to move to the Dallas county side of campus this summer. He applied for a lease in December 2014, but found out later that he needed to apply in February for summer 2015.

After applying again, Kujak asked for updates and repeatedly got the same answer.

“All they said was that they would roll out applications whenever they are available, which is really inconvenient for me or somebody who lives off campus and has a lease ending soon,” he said.

He didn’t hear back from them until June, which left him frustrated.

“They’re just making money off the application fee even though they have an extremely long waitlist,” he said.

By then, Kujak had already signed on a year-long lease off-campus. He couldn’t afford to pay $200 to $300 extra a month for a short-term summer lease in the hopes of moving to an on-campus apartment, he said.

On June 22, UV sent him an email saying he had been placed on its waitlist. The email stated that he could apply for a refund of the $75 application fee since the number of applicants this year had been high.

He got his refund for the 2015-16 cycle, but only because he wasn’t offered a lease to start with and he decided to get off the waitlist. Kujak said he shouldn’t have been allowed to apply in the first place.

“They are very over-saturated with applications,” he said. “If they know they won’t be able to fit everybody, then they should close off the applications at some point.”

All students placed on the waitlist were given the option to ask for a refund in late June according to Kwiatkowski said. He said UV received an exceptionally high number of applications this year.

There were more than 3,300 applications for a little more than 1,200 spaces available. By late June, it wasn’t likely that those on the waitlist would get an offer in time for fall, Kwiatkowski said.

There is a three-tier priority system for housing assignments in UV. Renewals, when students opt to continue living in the same apartment, are the top tier followed by transfers from residence halls and current UV residents. AES scholarship recipients receive priority over others, Kwiatkowski said, but only because their housing stipend is applicable to on-campus housing only. New and returning students who have lived off campus are the lowest priority, but leases are offered first-come-first-served based on the application time-stamp in the UV database.

There is a three-tier priority system for housing assignments in UV. Renewals, when students opt to continue living in the same apartment, are the top tier followed by transfers from residence halls and current UV residents. AES scholarship recipients receive priority over others, Kwiatkowski said, but only because their housing stipend is applicable to on-campus housing only. New and returning students who have lived off campus are the lowest priority, but leases are offered first-come-first-served based on the application time-stamp in the UV database.

“We think the way that we have everything set up is the fairest possible way for everybody to get equal treatment,” Kwiatkowski said.

From late March to mid-May, the people who are offered leases have a week to accept or decline.

Kwiatkowski said many students do decline or cancel leases within that period.

However, as the days inch closer to fall move-in dates, students usually have 48 hours to respond.

Kwiatkowski agreed that it is a difficult situation. But, he added, UV is aware that this late into summer, most people have already looked at other options for fall, which is why there’s a quicker turnaround. Moreover, they can continue to be on the waitlist for a later opening in the semester or in spring, he said.

“Our goal is to allow as many people as we can the opportunity to live here,” Kwiatkowski said.

Starting 2015-16, UV has stopped the shared bed option where two students could share the same bedroom. Kwiatkowski did not comment on what prompted this move.

“This is ridiculous, right? If (they) want to accommodate as many students as possible, then why … stop the shared option?” said Raj, an illegal campus resident, whose name was changed for anonymity.

He is an international student on a budget who said he would have lived on campus legally had the shared option been available.

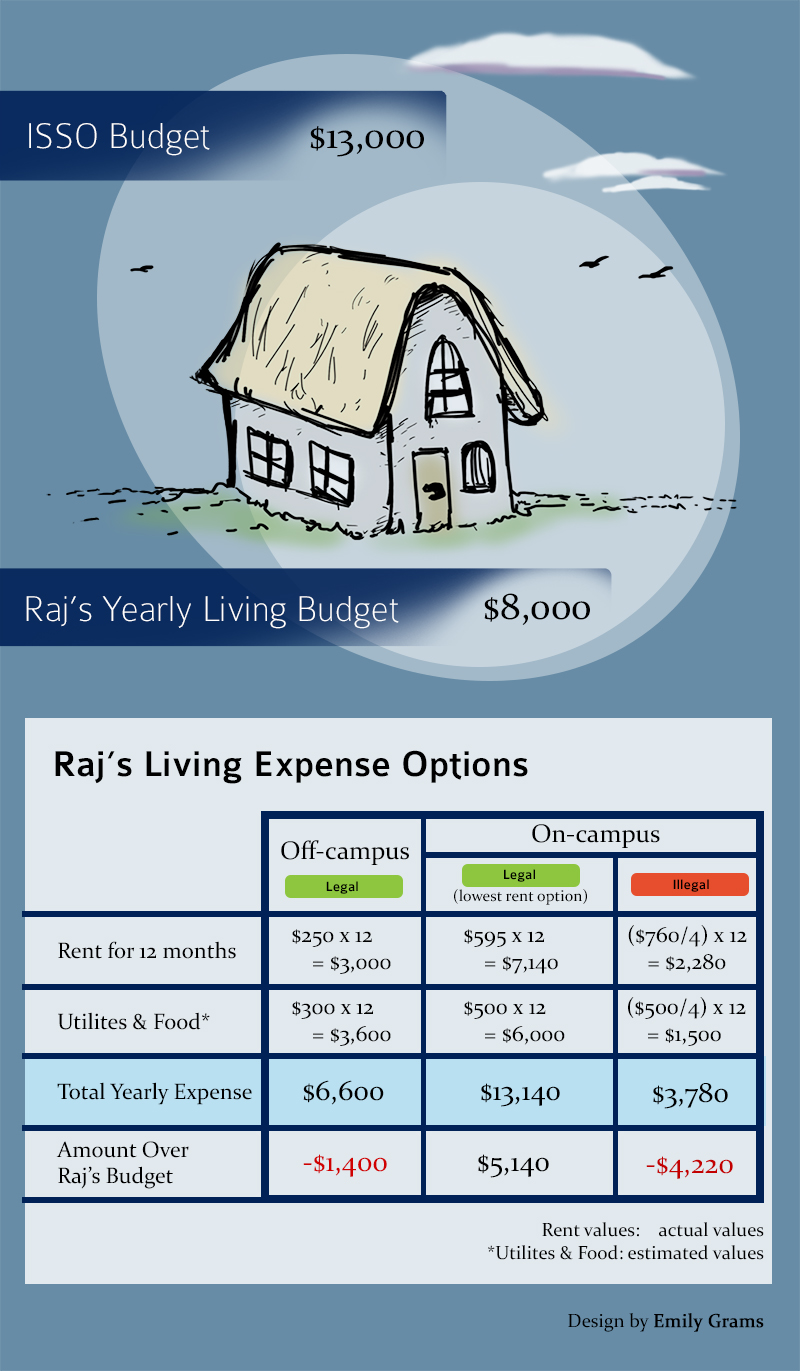

When he first came to the United States, he had a lease at Ashwood Apartments on McCallum Blvd. On-campus options were too expensive and Ashwood had a two-bedroom apartment available with four legal lease-holders at $1,000 a month. Raj was happy paying $250 a month plus utilities and living legally.

Then, last October, several international students were mugged on McCallum Blvd, he said.

Scared and shaken up, he and his roommates decided to move on campus to a two-bedroom, two-bath floorplan, which would cost them each close to $400 a month excluding utilities.

Unfortunately, only single-bedroom apartments were available, each costing $760, a price too high for any of them to pay. They took the apartment, but decided to live all four to the same unit, paying $190 a month in rent and getting to live on campus.

For Raj, the price of living illegally in cramped conditions is worth the personal safety of campus.

This year, he and his roommates have applied again, but no shared beds were available. All other students pay the rent stipulated by UV, but Raj said that is not an option for him and his roommates.

Raj didn’t want to rack up additional rent expenses if he could help it, and he wanted to live on a $7,000 budget per year. That’s possible in a community like Ashwood where he lived before. On campus, however, the lowest possible amount is $14,000 a year as a legal graduate campus resident.

Raj didn’t want to rack up additional rent expenses if he could help it, and he wanted to live on a $7,000 budget per year. That’s possible in a community like Ashwood where he lived before. On campus, however, the lowest possible amount is $14,000 a year as a legal graduate campus resident.

Every room has a maximum occupancy standard as per the city’s fire code. According to that, up to two residents can live in a one-bedroom apartment, four in a two-bedroom and four in a four bedroom in UV.

Illegal occupants create a dangerous situation for all other residents in the building, Kwiatkowski said.

“It’s important to the safety and comfort of the building, and to the quality of life within the campus community,” Kwiatkowski said.

Living illegally isn’t great for Raj either, but options around campus are very limited, he said.

Most international students can’t afford a car, so traveling from those communities would be a challenge. He said he understands why UV needs to price its apartments at the current rates, but UTD also has to meet international students halfway to amend matters.

“They also need to construct more apartments,” he said. “UTD keeps on admitting more students each year, but there is no housing for them. Either stop giving admissions out or provide enough apartments to students.”

Plans to build more apartments south of Phase 2 are underway, said Grant Branam, SG vice president.

Raj is close to 1,000 on the waitlist currently. UV has informed him that he doesn’t have a chance of getting an assignment before spring 2016. Raj isn’t sure that there is a point to it anyway. And he isn’t alone.

Some of his friends, he said, are in the same boat. They come back from fall internships in other cities and don’t want to get in on the waitlist for six months only to lose the application fee.

Then again, if Raj is assigned to a single-bedroom floor plan, he will have to take on an illegal roommate. He can’t pay the full rent on his own.

Raj says living illegally is an adjustment that has him looking over his shoulder.

“It’s a constant fear,” he said. “We don’t show it but it’s always there in the back of our minds. If we’re caught, where would we go?”