After a recent bout with food poisoning, a UTD student co-created SafeDish, an app that makes it easier to find health inspection information for nearby restaurants.

Computer science senior Caleb Jiang noticed how inaccessible health inspection data is when he got food poisoning after eating at Chipotle. Jiang said that while restaurants are required to have copies of their latest health inspections available upon request, the data can be very difficult to find online.

“We thought, you know, it would be pretty cool if we could make this hard-to-find government data much more accessible to everyone so they could be more informed consumers about what food they eat,” Jiang said.

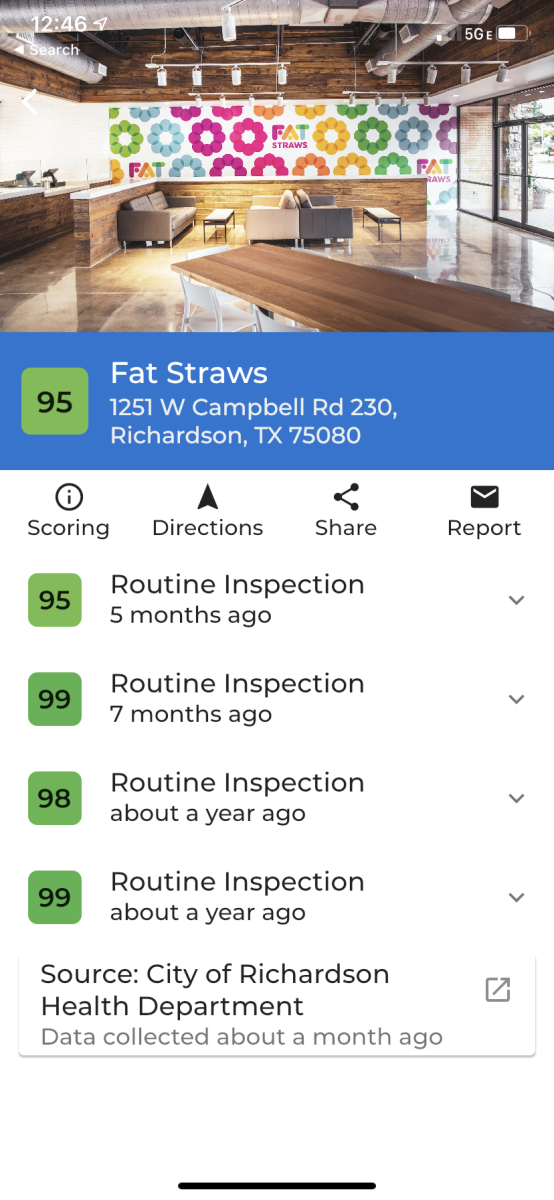

SafeDish aggregates health inspection data from food establishments and displays inspection scores, sanitary violation information and links to the inspection reports. Users can search for restaurants or use their location to view data for nearby restaurants. According to the coverage map, data is available for restaurants in the DFW and Austin areas, as well as for Chicago, New York City, San Jose and municipalities across Tennessee and Georgia.

Jiang said that current coverage depends on how easy it is to get data from different areas: Tennessee and Georgia have a statewide system that handles health inspection data, and they use the same software as Tarrant County, so the code could be reused.

“When we do write new features for new regions, we try to prioritize the amount of people covered per hour [of work],” Jiang said.

Jiang co-developed the app with Blake Bottum, a friend from high school who is now a computer science student at UT Austin. Bottum said that he recalls looking for health and sanitation information for a restaurant in Austin before the two conceptualized SafeDish. He was unable to find any data online.

“To be honest, that may have been a failure of the state health department, and if that’s the case, then the app doesn’t solve that anyway,” Bottum said. “But just knowing where to look was half the problem.”

The two came up with the idea for SafeDish in September and started working on the front and back ends over winter break, Jiang said. While they are continuing to work on adding data for new cities, Bottum said, it’s a time-consuming process made more difficult by the fact that inspection data isn’t standardized.

“Our expansion plans are dependent on if we can find other places that are easy to fetch,” Bottum said. “A lot of counties and a lot of municipalities in this country do not have easily formatted data sets to access programmatically.”

For example, North Richland Hills publishes scores in a PDF that’s not computer-readable, while Arlington has a database that’s in a completely different format, Jiang said. The Park Cities area of Dallas, meanwhile, doesn’t have any kind of digitized records.

“If you want all the health reports, you have to file a public information request and pay a bunch of money,” Jiang said. “Even in DFW, it’s very hard to get full coverage of everything.”

Jiang said that user response is difficult to measure since people tend to use SafeDish just once or twice to check scores on restaurants they frequent. Because users don’t reopen the app once they have the information they need, the user retention rate is low.

“Our app is more of a tool than something that’s supposed to suck you in, like Facebook, that constantly refreshes with new content,” Jiang said. “I don’t see how we could have refreshing content considering we’re limited by the data the city provides.”

Jiang said that ultimately, SafeDish can help people be more informed about what’s happening in the background to keep communities safe and healthy.

“Your local government does a lot of things for every aspect of environmental and public health that you just don’t know because 99% of the time, it goes smoothly,” Jiang said. “I think that if people have access to that data, they can make a lot more informed choices about day-to-day things.”