For the first four nights of Ferguson’s (intercommunity) protests, it was difficult to tell by television alone if the Missouri suburb even existed. While CNN and its peers settled neatly into their primetime routines each night, hundreds of the town’s tech-savvy protestors flooded social media sites in a firm move for proper documentation. The Ferguson Police Department had already began its use of military-grade weaponry against those who dared to crowd on West Florissant Street, and most coverage of the incidents that followed the police’s arrival flowed through Twitter often and with a tinge of desperation, as if no one was really sure if the world at large would really believe them. For four days, thousands of Tweets, Vines and videos were made to capture astonishing clips of protestors being maced, sprayed with tear gas, shot at and otherwise bodily threatened for protesting within their own neighborhood. As if granting their approval, major media outlets remained eerily silent on the matter, only commenting once to note unfortunate looters ransacking stores miles away from the scene. It wasn’t until the untimely arrest of Huffington Post journalist Ryan Reilly — who, ironically, immediately took to Twitter to detail the experience hours later — that a newfound interest in the rally was born, and the lure of TV time funneled journalists in by the busload. Yet, for all the media presence in Missouri, so much of the media coverage on the town’s actions remains wildly inaccurate or ignored.

For these reasons, I believe that the media has failed Ferguson. More importantly, I believe that if it wasn’t for “online” or “Twitter” activism, the world would have never known about Ferguson or Mike Brown in the first place. Perish the thought. In an age where social media has proven itself a political tool numerous times, Ferguson became an international case study for anti-black police brutality and racial profiling in ways that would have been inconceivable only a decade prior. By the sheer force of will — and hundreds of Twitter accounts — the protestors in Ferguson have managed to not only grab national attention and hold it for days at a time, but also rally against the poor narrative being created by major media. And because most of this grassroots coverage is available by Twitter, almost anyone and everyone can (and has) participated in documenting what has transpired so far: councilmen, celebrities, residents and everything in-between. Visiting the #Ferguson tag on Twitter is a dizzying experience still, with updates coming in from a variety of perspectives by the second. In Ferguson, we see “online activism” at its best, right down to its overpopulated Twitter hashtags.

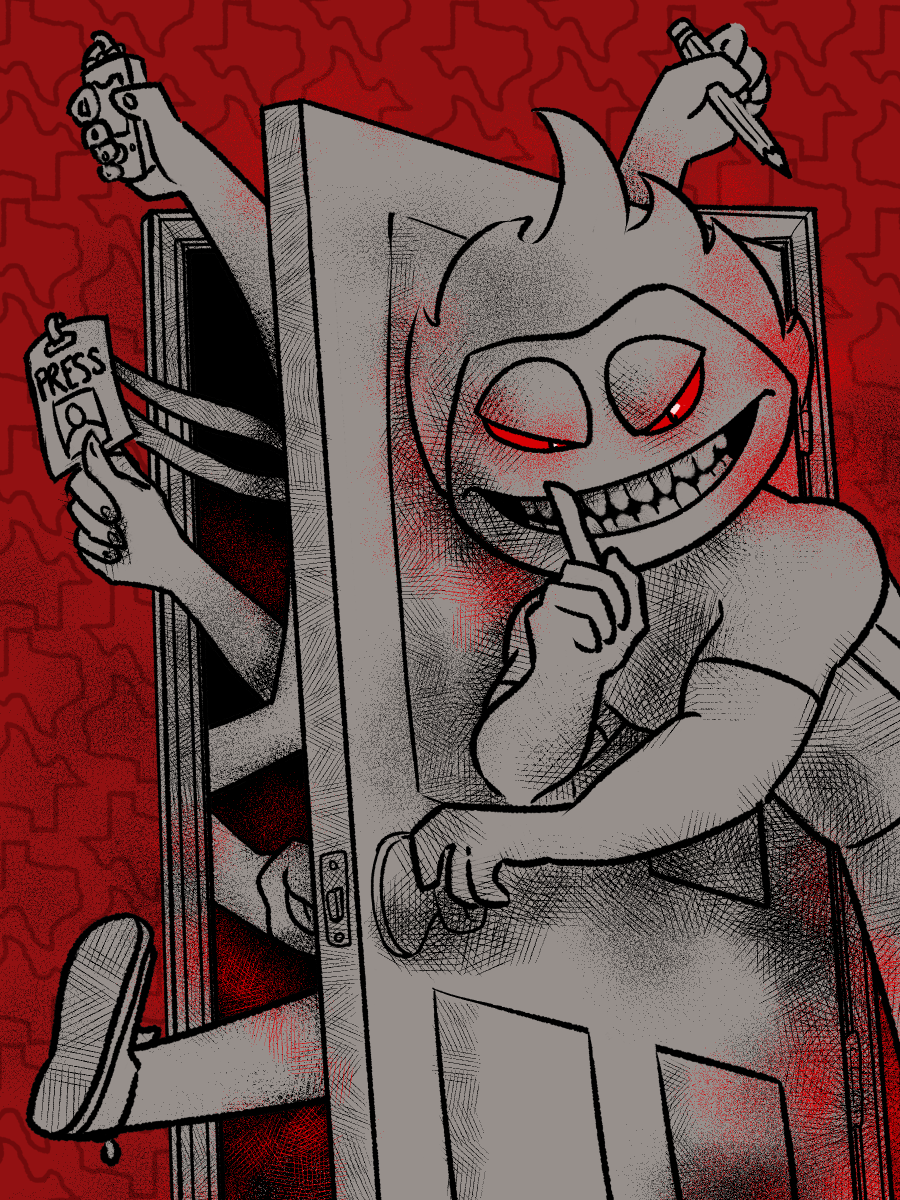

Online activism as a concept can be very polarizing. In activist circles (it doesn’t matter which one), you can expect to find people who sing its praises or curse its popularity. So much of what we know about activism and movements points to physical struggle as a signifier of “real” work taking place. The problem with online activism, its detractors will tell you, is its lack of this “physical” component, which invalidates its claim on “real” activism. Online activism — synonymous sometimes with “Twitter activism” or “social justice” — earns its derision by seemingly removing “real” activists from the sidelines to tweet or reblog their way through movements. With the rapid rise of technology, the concept has become a buzzword of sorts, eliciting debates of whether or not its presence marks a natural evolution in technology or a decline in activism itself. One only needs to look at Ferguson to understand how big of a role social media can play in activism, with protestors actively using Twitter to call out misrepresentations of incidents with Ferguson police officers or major media’s attempts to smear the reputation of Mike Brown. Despite its shaky stance, online activism allowed protestors to effectively grab a piece of the national narrative surrounding their neighborhood and, even more surprisingly, hold major media accountable for its failures.

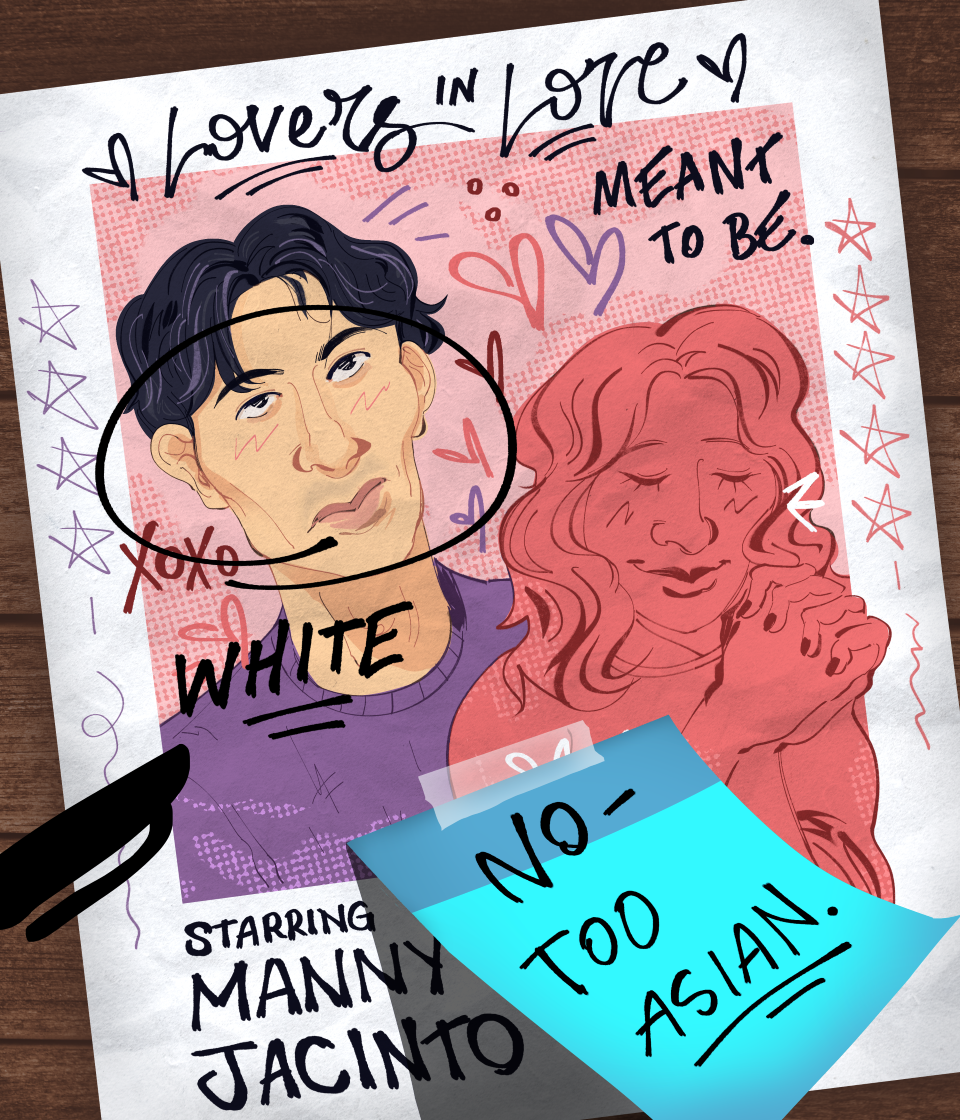

Such failures, surprisingly, have been frequent and unparalleled. Some have been simply in poor taste, like the constant misrepresentation of the protests as “riots” or the media’s sensationalizations of looters ransacking the city (Ferguson residents have since debunked claims of looting, noting that the looters and the protestors were two distinctive groups.) Other failures have been downright disappointing, like the media’s inability to recognize Mike Brown’s death as a symptom of institutional racism and a critical issue within black and Latino communities. Some have even been comical, like Fox News’ use of Martin Luther King Jr. to placate what it believed were violent protestors. Overall, most of these failures have been harrowing, such as the smear campaign launched against Mike Brown that includes an irrelevant toxicology report identifying marijuana in Mike Brown’s system and the now-infamous clip of “Mike Brown” robbing a convenience store as unspoken “evidence” for the teen’s gruesome death. (On August 19, when thousands of protestors crowded CNN’s Atlanta studio in protest of this particular smear campaign, the news outlet couldn’t even find time to make a tweet about it.) Whatever their causes, all have effectively muddied the national conversation surrounding Ferguson and made it difficult to connect facts and experiences. The fact that justice for Mike Brown stands equivocally in so many Americans’ minds is a prime example of how much damage has really been done.

Major media’s failure to consistently and accurately report all incidents in Ferguson has created a dangerous opportunity for sloppy or biased journalism that should worry many of us. These outlets’ positions in news and politics carry much weight for the many Americans who use them as sources. They are responsible for effectively driving the nation’s attention — what they talk about, we will talk about. When such an outlet reports an incident incorrectly or not at all, it has a substantial negative effect on the national opinion on Ferguson. For example, when such outlets ask about the marijuana in Mike Brown’s system instead of why Darren Wilson used nine shots to end Brown’s life, the national conversation is lost to fear-fueled assumptions about black men and drug use. When our media fails to ask the right questions, we all suffer under the insurmountable weight of injustice.

There was a time in this country when journalists were the only barriers between an oppressed citizenry and a dominating national government. Like watchdogs, muckraking journos and the publications who loved them warred an effective campaign against the corruption and deceipt of unrepentant villains. In 2014, it feels as if the tables have changed. Our news comes to us faster than ever, yet the ethics of journalism has changed drastically, leaving a once-unknown Missouri suburb to police America’s oldest “policemen.” Journalists have transitioned from the government’s biggest nightmare to its personal megaphone, and Ferguson is just another example of what that can mean for citizens around the country, should they ever decide to hold a protest of their own. That’s why it’s important for us as citizens to be able to recognize when these misrepresentations are happening and to be confident in defending our community the way Ferguson has defended itself. It’s important for us to be able to talk about why such failures happen as well, and how factors like racism and classism can influence the media we consume, and what we ultimately believe about ourselves and each other.

Again, the media has failed Ferguson. It has failed Mike Brown. But if there is any lesson to be learned, it can likely be found on the hundreds of Twitter accounts run by “online activists” doing some very “real” work on the streets of Ferguson. I implore anyone still concerned with the merits of online activism to take a second look at Ferguson — and ultimately, the true power of technology.

Categories:

National media failed Ferguson

August 25, 2014

Story continues below advertisement

0

More to Discover