Corrections: In a previous version of this article, the definition of pansexuality was incorrectly stated.

Also, attribution for policy changes on campus that benefit the LGBT community were incorrectly stated.

The Mercury regrets these errors.

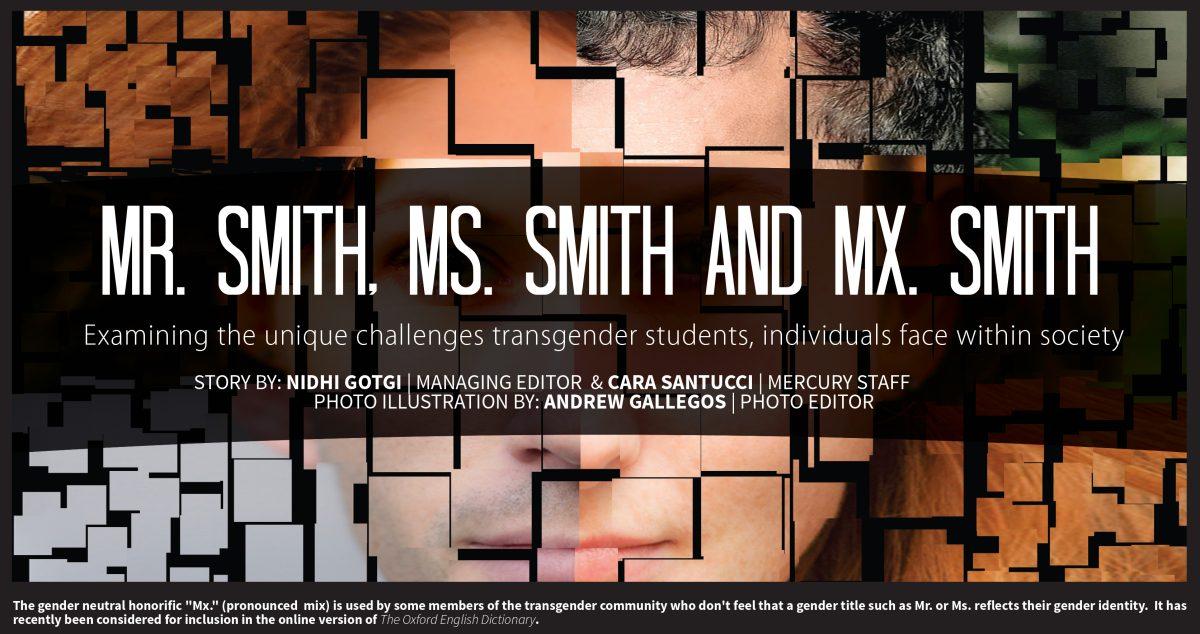

-Editor’s Note-

Due to concerns about their safety and privacy, no photos of the transgender individuals interviewed for this story were taken and some of their names were changed or partially redacted.

Also, some transgender individuals do not identify with a specific gender. In this story, a source is referred to with the pronouns “they”,”their” and “them” to reflect their gender identfication.

They remember not feeling right about being a girl. They would wear loose t-shirts and huge khaki pants to hide the feminine attributes they were born with. The idea of telling their family what they were experiencing scared them because they had no words for it themselves.

For most of their life, they felt out of place.

Angel is a junior who identifies as agender, meaning the absence of having a gender. Growing up in a Pakistani household, where everything was heavily gendered, made being transgender very difficult.

“It’s not safe to be transgender, especially in the Desi community and the Pakistani community,” Angel said. “My mother was very upset. She wanted me to fit better. She wanted me to look like the girls in my community.”

They explained that transgender people are stereotypically known as home wreckers in the Pakistani community.

“They are said to be intentionally trying to shame the family,” Angel said. “This perception of people as being intentionally harmful or intentionally full of malice, it scares me.”

Trans Experience (first inklings)

There are approximately 700,000 transgender individuals in the United States. Stories like Angel’s, where young people feel confused and scared when they start to realize that their gender doesn’t match the sex they were born with, are common within the transgender community.

Alexander Kujak, a healthcare studies senior and a transgender man who was born with a female sex, first felt an inkling of this gender dysphoria when he was in elementary school. As a child, he was frequently called a tomboy and recalls not truly feeling like a girl.

“My parents always said (I’d) grow out of it,” Kujak said. “As I got older, it just morphed into, ‘I’m not a tomboy. I’m a boy.’”

At the time, he said he thought he would have to be a girl for the rest of his life. Back when he was growing up, Kujak remembers “transgender” was a highly stigmatized word. It was often equated to cross-dressing, given a negative connotation and denounced publicly.

Not wanting to align with that definition, Kujak distanced himself. It wasn’t until he entered high school that he discovered what the term really means: that one’s biological sex at birth does not align with one’s gender identity.

“It was kind of like a light switch turned on,” Kujak said. “(It) explained everything I experienced when I was younger.”

Not every transgender person experiences the revelation of their actual gender as though a switch had been flipped.

Zackary, a junior in literary studies and a transgender man, described his discovery as gradual at first, and then all at once.

The summer after his freshman year, he lived in a male friend’s apartment. Over the course of the year, he found that the more feminine habits he had started to fade away. He stopped wearing makeup, dresses and heels. These behaviors began under the influence of his mom, but were continued as he compensated for feeling uncomfortable with his gender. Once he was no longer being pressured to be ‘a girl,’ he became free to be the person he was: a man.

Zackary said that these feelings of dysphoria are very common in transgender individuals.

“It’s kind of weird because I had the same experience when I realized that I was not straight,” Zackary said. “I think one day I was just like, ‘Wow, I think I’m not straight,’ and it was like (all) the previous years made sense.”

A major element of the transitioning process involves the medical changes. This deals with everything from hormone treatments to mastectomies.

Before any physical changes can take place, however, an intricate web of checks and balances must take place first.

This requires going to counseling to get a letter, going to a doctor that will treat transgender patients, paying for hormones and finally waiting for gender confirming surgeries based on insurance plans.

A significant barrier to medical transition is the cost. Many insurance plans, especially those in Texas, are trans-exclusive, meaning they don’t cover anything related to transitioning. Kujak ended up paying for his double mastectomy out of pocket, a procedure that costs $6,000.

For others, just deciding to pay just for hormone therapy still costs a significant amount of money.

“My friend spends $70 a month on hormones… and that’s not even counting the doctor visits,” Zackary said. “It is very expensive.”

Because insurance plans are trans-exclusive, college students frequently don’t have the funds to pay for medical treatments.

Even if a transgender person has the means to access surgery or hormones, they might decide not to. Gender confirming surgeries can be very invasive and require several weeks of healing time.

Sarah Hodgkinson, the student development specialist in the Women’s Center, said not all transgender people feel surgery is necessary for them.

“A lot of society kind of waits to confirm someone’s identity until they’ve had some kind of gender confirming surgery or hormones,” she said. “The number one thing I want people to do is not wait for that, because the individual may not ever feel like that’s something that’s necessary for them in their gender identity or (because) of the significant costs and legal barriers.”

Social Transition (family/dating/friendships)

After transgender people have made their transition, coming out to the public can be a complicated affair. Some transgender individuals are out to their friends, but not their family. Some are out to their family, but not their friends.

According to The Huffington Post, 102 acts of violence against transgender people occurred within the first four months of 2014 across 14 countries worldwide. Because of the violence and harassment publicly transgender people face, the decision to come out is not taken lightly.

Zackary attributes his ability to show his peers who he really was to his friends at Pride, a social organization for LGBT students.

“I personally don’t know if I would have been able to come out if I didn’t have such great friends that were so supportive,” he said.

According to Zackary, Pride has anywhere from 40 to 60 people on a regular meeting day. He estimates about 12 of those participants are transgender individuals that are very connected with one another. The transgender students in Pride frequently take classes together so they can be there for one another.

“I’m already out in my classes and it was hard. I’m not going to say it was easy,” Zackary said. “There were a couple students, I don’t think they were rude, but I think they didn’t know how to interact with me.”

He said he was comfortable going public with his gender because he is willing to have hard conversations with people.

“I feel like if I did things like that, it would make it easier for other trans people,” Zackary said.

Coming out to family can also be a complicated affair and can sometimes lead to other discoveries. For Zoe, a software engineering student and a transgender woman, her attempt to tell her family did not go very well.

Her family had a hard time believing that she was transgender because she hadn’t acted clearly masculine or feminine when she was young.

To add on to this, Zoe’s family had a secret of their own: they had never disclosed to Zoe that she had Asperger’s syndrome.

“It was confusing enough having Asperger’s and not knowing about it until then,” Zoe said.

This helped to explain why her family didn’t believe she could be transgender. A misconception stemming from the extreme male brain theory led them to believe that people with autism spectrum disorders couldn’t be transgender.

“That [theory has] since been debunked,” Zoe said. “It did play a role [in how my family reacted]. That was the reason that [they] used.”

Angel, who isn’t out to their family, came out last year to their boyfriend and said that they’re only out to a close circle of friends.

Angel has considered telling their parents, but they said that although they recognize that not all members of the South Asian community are wholly opposed to LGBT terms, they feel that their parents aren’t ready to face the truth.

“If they can’t even find it in them to say the word lesbian, you can’t even begin to approach the word transgender,” Angel said.

Another aspect of coming out is navigating the dating scene. This gets more complicated if the other person does not know their partner is transgender.

“For me, a transgender man, all I care is that the partner I’m dating is interested in men,” Kujak said.

Violence against transgender people is already a concern, but it is especially prevalent in dating scenarios. “Transpanic,” where a transgender woman and a cisgender man—a man who aligns with his assigned sex at birth—go into a bedroom and the man attacks the woman in a panicked state after discovering his partner is transgender, is common.

Kujak said it is perceived as an obligation in society to tell dating partners if one is transgender. He said it is more common to drop hints around a partner to gauge their reaction to discover if coming out would put their safety at risk. For example, a transgender person might ask what a partner thinks about transgender celebrities like Laverne Cox or Caitlyn Jenner. If they had a negative response, Kujak says he usually just makes an excuse and stops seeing them.

“Once we kind of feel for that barrier, that’s… when we feel it’s more appropriate to tell,” Kujak said.

Currently, Kujak is dating Jerica Bartleson, a cisgender woman who is pansexual. Pansexuality is generally defined as not being limited in sexual choice with regard to biological sex, gender or gender identity.This does not imply that bisexuality excludes transgender people.

“I find it easier to say pansexual, because for me… the gender doesn’t play a role in how I’m attracted to a person,” Bartleson said. “It’s how we connect as people.”

She is not a student at UTD, but works in the area. She has been dating Kujak since September of 2014.

Bartleson first met Kujak when she moved to Texas from Arizona and lived in an apartment with him and a few friends. As they got to know one another better, they gradually became friends before beginning to date.

“I met Alex and we connected on a friendship level first and then eventually connected on an emotional, relationship level,” Bartleson said. “We’re happy, so it doesn’t really matter that he’s not a girl because he’s who I want to be with right now.”

Bartleson has become much more involved in the LGBT community since dating Kujak. She didn’t have much experience with transgender individuals before moving to Dallas.

“It’s not any different than dating someone who was born… cisgender,” Bartleson said. “All your stereotypical guy tropes are still there.”

Legal Transition (policy changes/gender marker/name change)

For transgender people, the legal transition can be almost as difficult as the physical and mental ones.

Legally changing name and gender on official documents for transgender people can be especially complicated depending on where they live.

UTD is on the border of Dallas County and Collin County. According to Kujak, there are almost no judges who will grant name and gender marker changes in Collin. In Dallas, there are approximately 17 judges who will grant the request. This becomes an issue for students living on campus, as the border between Dallas and Collin cuts between apartment phases, leaving some students in either county.

Gendered bathrooms also raise an issue for trans people, especially early in transition.

“To some extent, it’s a bit of a safety issue in that if you’re visibly trans and in the men’s room, then there’s a risk of violence,” Zoe said. “If you’re visibly trans and in the women’s room, then there’s a risk of very severe words.”

Zoe discussed using only unisex bathrooms for a while after her transition and how not all public buildings are equipped with enough of these facilities.

“[It] could sometimes be a little bit of a problem that most buildings have only one,” she said. “And if you’re trying to go there on break from work or in between classes, you can just be plain out of luck.”

Currently there are 13 accessible unisex bathrooms across UTD’s campus, located in the Activity Center, ATEC, ECSS, Founders, SSB and SOM II. Rainbow Guard has just finished cataloguing single stall bathrooms at UTD. Progress is being made to convert these restrooms to be gender inclusive and signs will be put up to reflect the change. All of the policy work is done through the LEAP initiative—an advocacy and programming initiative that works to protect the sexual orientations and gender identities of students on campus—and the Rainbow Guard.

On campus, policies for transgender students vary depending on the department. Through collaboration between the Women’s Center, LEAP and the registrar, a process has been created for students to enter their preferred name on the registrar’s website. The preferred name will then go into class rosters on Coursebook. The LEAP Committee is currently working on potentially changing how a student is listed on their Comet Card. Along with these advances, the Activity Center allows students to play on any rec team that matches their gender identity.

“We’re starting to have conversations about how we can have policy that really protects and honors (transgender) individuals,” Hodgkinson said.

The Future of Transgender Rights

Approximately 41 percent of transgender teens and adults attempt suicide at some point in their life according to The Williams Institute at UCLA. This number jumps up to 45 percent for transgender individuals age 18-24.

According to the National Center for Transgender Equality, an estimated 20 to 40 percent of homeless youth are part of the LGBT community and one in five transgender people have been discriminated against when seeking home in the United States. One in ten have been evicted from their homes because of their gender identity.

Angel said these, and other issues, have yet to be addressed by society.

They said programs that combat substance and alcohol abuse and mental illnesses and eating disorders among transgender people need to be implemented.

Above all, research and talking to transgender people will provide ways to find solutions to these problems, they said.

“I would say looking into local initiatives, for example, the Trans Pride Initiative or the Transgender Law Center, would help with answering people’s questions on how to support transgender friends and their families,” they said.

Sociology sophomore Cody Kuhn, who is the programming director for Rainbow Guard, pointed out that there’s even stigma against transgender people within the LGB community.

“It’s difficult because even within LGBT communities, the ‘T’ is often forgotten or left out,” he said.

While Angel acknowledged that the Supreme Court ruling that legalized same-sex marriages across all 50 states brought a lot of attention to the LGBT community, they pointed out that there’s still a lot that still needs to be done for transgender people.

“It’s a win, but it’s not the whole ten yards,” Angel said. “I would say it’s something that everyone in the community can venerate. It’s just (about) doing that while also recognizing that it’s not the last step. Transgender people have more milestones that need to be met.”