Take an inside look at how UTD’s mathematical scientists operate, solve problems using high dimension math

When people think of research, they imagine a scientist in a white lab coat pipetting chemicals or culturing cells on a petri dish. But when asked to consider “math research,” what comes to mind? What does pure math research entail?

This fall, the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics inducted seven new tenured and tenure-track faculty. Among them, Baris Coskunuzer and Stephen McKeown conduct research in math, while Qiwei Li conducts statistics research.

“Pure mathematicians are not really interested in the real-life applications,” Coskunuzer said. “They are trying to solve nice puzzles, which give you interesting relationships between objects.”

Coskunuzer got his first taste of math as a high schooler in Turkey, where he enjoyed classes in abstract math. He majored in math in college, and as a Ph.D. student at Caltech, his advisor introduced him to geometric topology. Given his knack for visualizing objects in high dimensions, he decided to enter the field, investigating the shapes and classification of high dimensional objects.

“In the pure math, after (the) third or fourth year of PhD, you start to have a sense of some beauty in the subject … you can think of pure math like an art,” he said. “ You go deep in this sea, and you discover treasures.”

Daily tasks in math research include studying the publications of other mathematicians, attending conferences and collaborating with colleagues, Coskunuzer said.

Like Coskunuzer, McKeown said that a large part of math research involves reading the work of others.

“A lot of the time is (also spent) sitting at your desk with paper and pencil and doing calculations or staring at the wall for that matter, thinking really hard,” McKeown said.

McKeown was first drawn to math when he read a book about geometry and relativity in high school.

“In college I started taking calculus for the first time, and I really loved it,” McKeown said. “I was surprised by how beautiful math could be, so I started reading popular math books … I got some sense of the field of math … and I found that very exciting.”

At the same time, McKeown was also interested in becoming a lawyer. He finished law school and passed the bar exam before returning to the field of mathematics.

“At some point I realized that I missed math and wanted to do that instead,” McKeown said.

McKeown concentrates on conformal differential geometry in his research. Conformal differential geometry is the study of spaces where angles, but not lengths, are well defined.

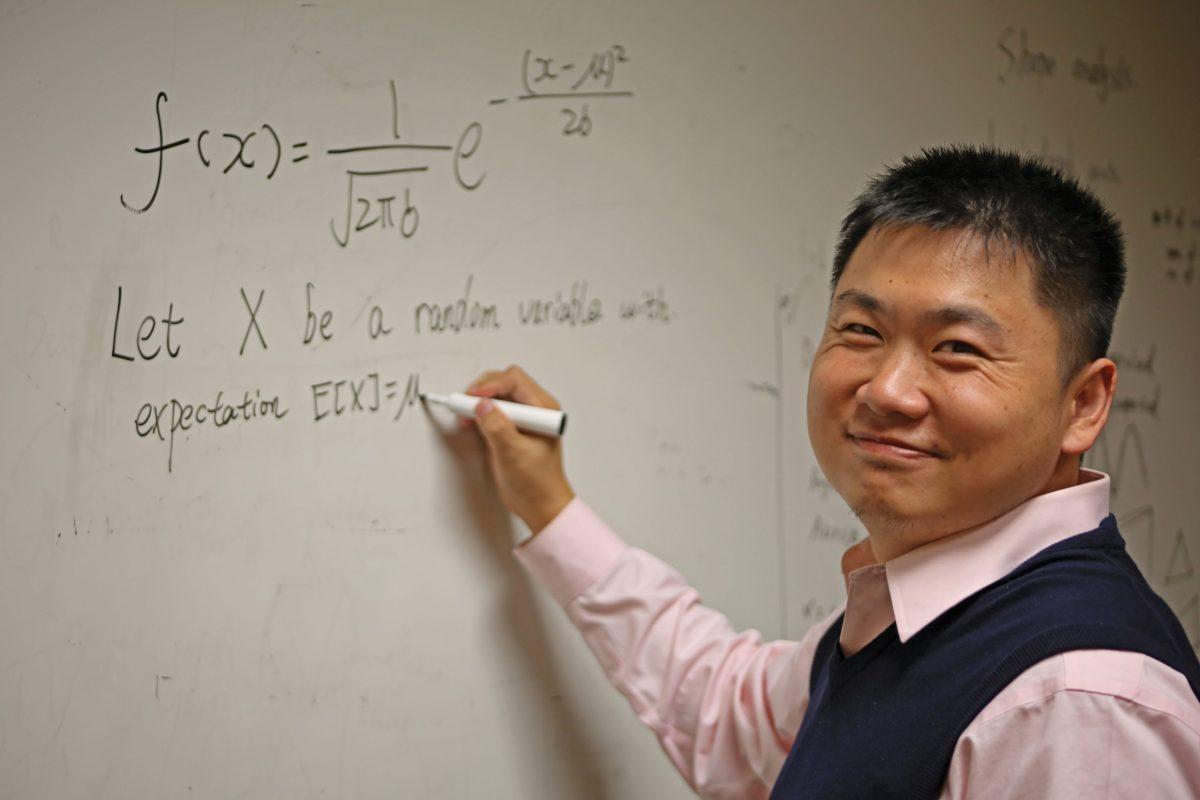

In contrast with pure math research, Li said, statistics research centers on application, especially in medicine or biology.

“Statistics is the science about data, because the data can reveal lots of interesting things about the body and the world,” Li said.

Daily tasks in statistics research include collaboration with biologists, chemists and doctors to collect and analyze data using computer models and statistical analysis software.

In college, Li majored in electronic engineering. As a master’s student, Li took a data mining course, where he classified the quality of photos based on different metrics. Li’s interest in photo classification led him to change his major to statistics.

“I didn’t like the electronic engineering research, I wanted to do something new (and was) interested in data analysis,” Li said.

Li uses Bayesian statistical tools to draw conclusions in two areas of application, digital pathological images and microbiomes, which are collections of microorganisms, using both data and prior knowledge. High resolution images of pathological tissues can be analyzed by a deep learning AI to identify different types of cells, Li said. The patterns of cells are statistically quantified and used to predict patient survival outcome.

“If you are suspicious that you might have cancer … I want to confirm that,” Li said.

Li also identifies biomarkers that can be used to predict colorectal cancer by quantifying bacterial abundance in the human microbiome.

Research is often rife with challenge, as all three professors can attest to. In math research, one can get stuck on an aspect of the problem for months, even years. In statistics research, a major challenge is locating datasets that can prove the merits of one’s methodology.

“You find yourself at this side of the chasm looking across and you just don’t know how you’re going to get across, and I think that’s the most frustrating thing,” McKeown said. “Our students feel frustration because they don’t know how to solve a problem, but we do too.”

McKeown said that he had once been stuck on one problem for three months, another for nine to ten months, and is still grappling with a third problem, which he set aside a year ago because he did not see a solution.

“One of my mentors in undergrad said, ‘the mathematician spends 90% of his time depressed and 10% of the time elated,’” McKeown said.

To bridge that chasm in a problem, McKeown may write out arguments or read papers that reference a similar concept. This helps him gain a new perspective on the problem and adapt other techniques to his situation.

“The actual process of sitting down and doing math, I enjoy,” McKeown said. “I think that moment of when you actually understand something you didn’t before is … in some sense why you’re a mathematician, because that’s really rewarding.”

He also appreciates how complex math ideas are built around simple fundamental concepts.

“The biggest, most beautiful proofs in the subject are reducible in some sense to (the) little things in the most pleasing way,” McKeown said.

As advice to aspiring students, McKeown suggests taking a variety of math classes and participating in an undergraduate research project to find out whether math is a good fit.

“Challenge yourself and put yourself in classes where you’ll have to prove things, (to experience) a small taste of getting stuck on something (and of) the frustration and the excitement and joy of getting past it,” McKeown said.