Movie debates ethics of companies that mark up prices of medicine

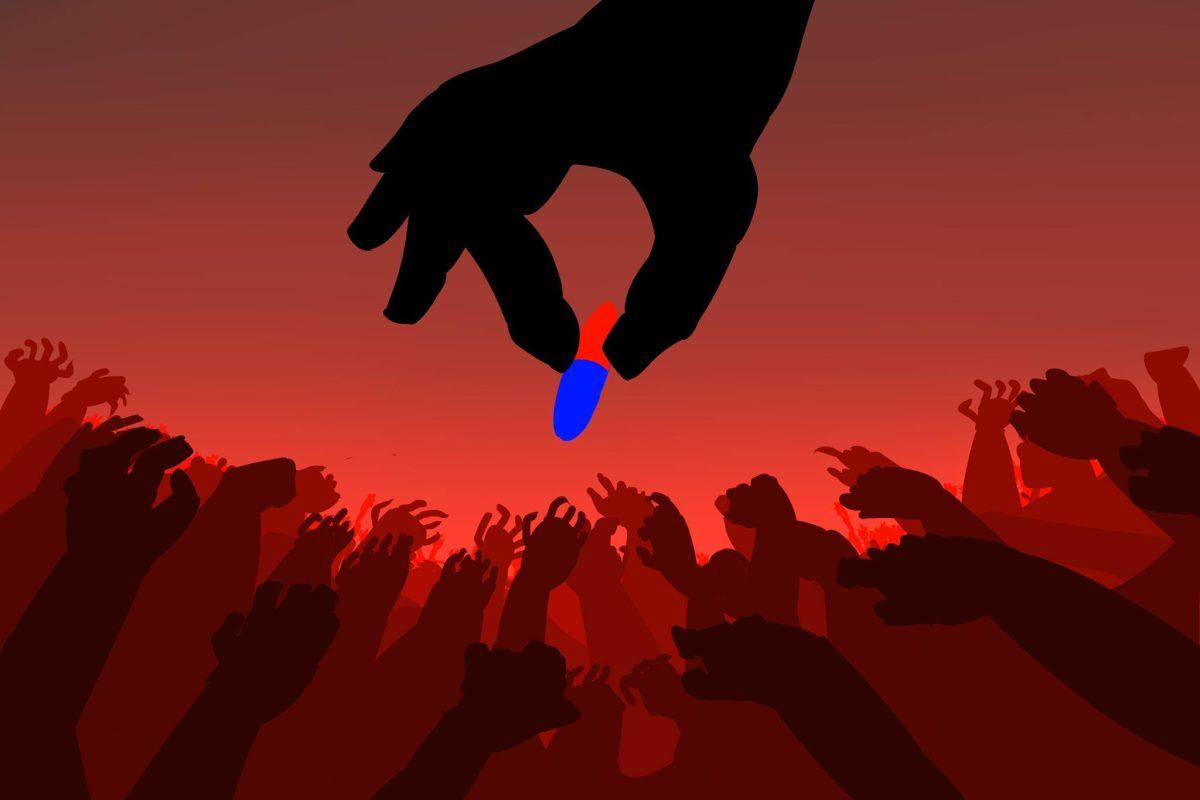

As the lights dimmed in the Jonsson Performance Hall on Jan. 20, the audience of students and faculty members focused its attention on the visuals taking over the blank screen. Within the first few minutes of the documentary preview of “Fire in the Blood,” the message of the film was portrayed through a cartoon sketch.

The sketch depicted the Statue of Liberty, her face scrunched up in a scowl, as she held a bag labeled “Drugs” and looked down on the vast crowd of outstretched hands reaching for the bag.

“The question that I think the film poses (is) ‘Do pharmaceutical companies have a moral obligation to save lives?’” said Assistant Professor of Film and Aesthetic Studies Shilyh Warren. “This film documents essentially the pharmaceutical companies’ patent control over antiretroviral drugs and the way that lives are essentially expendable in the rest of the world.”

The film, which was presented by the Center for Values in Medicine and Science and Technology as part of the Viruses, Vectors and Values Lecture series, depicted the daunting realities of HIV and the millions of deaths faced by citizens of developing countries resulting from the disease. According to the documentary, blocked access due to sanctions and patents on ARV drugs enacted by pharmaceutical companies is to blame.

The film delivered insight not only from visionaries at the forefront of aiding developing countries, but also from those fighting the battle of HIV epidemics. Experts varying from economist and Pulitzer Prize winner Joseph Stiglitz to former president Bill Clinton were featured in the film.

Seema Yasmin, a public health doctor, UTD faculty member and journalist, has had extensive experience researching HIV and AIDS. In 2010, she went to Botswana for a year as a Clinical Research Fellow.

“I remember some of the conversations really well,” she said. “For example, a man came in who had HIV and who had a (Cytomegalovirus) infection in his eye because of the HIV. The clinic that I worked in would try and pay for people’s medication and also give them money to buy food and stuff. The discussion that he was having was, ‘Do I use this money to buy food and medication, or do I use this money to pay for the funeral of a relative who just died of HIV?’ … If you’re having to decide that, it’s great to giving people medication, but they haven’t got food to eat, then what’s the point?”

Mark Tschaepe, an assistant professor at Prairie View A&M University who also serves on the Board of Directors for AIDS Foundation Houston, facilitated the discussion panel. Some topics centered on the stigma surrounding HIV, the varying perspectives of those featured in the film, why Big Pharma is considered the adversary and the philosophy behind the views of the community about HIV.

“Usually when we are talking about illness, we are talking about people who are impoverished (or) who are suffering the most and this isn’t simply with regard to unavailability of medication. This is also with regard to susceptibility of the disease,” he said. “I think there really needs to be an increased level of education not simply on what medications are good (and) what medications are effective, but also how do we address poverty in addressing disease.”

The panel also discussed the statistics that the documentary stated. According to the film, which was made in 2012, the top 10 pharmaceutical companies made more than the profits of the top 493 companies on the Fortune 500 list combined.

In addition to the profound amount of revenue generated by Big Pharma, the cost of making one pill for HIV — also called an antiretroviral cocktail — is roughly 5 cents. The annual cost of a patient receiving HIV medication amounts to approximately $15,000 annually. For a person with HIV who lives in South Africa and earns an average weekly wage of $68, the cost for ARV drugs is astronomical.

“Companies do that to capture what economists call normal profits,” said Abigail Durden, an economics junior, during the discussion session. “It would make a lot of sense to just say, ‘Why don’t we just charge 10 cents a pill, and, with the millions of people that are HIV positive, why don’t we cater to all of them, boost up our volume and make a ton of money?’”

Opinions on the flaws of the documentary, from the cinematography to the content, were shared during the discussion.

“What I didn’t like in the film was the implicit (and) explicit critique of the patent system as the cause of the problem,” said Fred Grinnell, a professor at UT Southwestern. “New drugs are very expensive to bring to market and often cost more than $1 billion. (Research and development) leading to new drugs frequently is carried out by universities with federal funding or by small companies, but the very high costs of human clinical studies required to demonstrate efficacy and to gain FDA approval of new drugs typically are paid for by Pharm. Without patent protection and the potential to profit when new drugs succeed, Pharm would not be in the drug development business and we would have no new drugs.”