James Baldwin, outspoken African American author and civil rights activist in the late 20th century, wrote extensively on race and white America’s influence on African American identity. With the writing’s personal significance to Baldwin, however, it was not just about politics. His most discerning work manifests itself in his letters, personal musings and public debates.

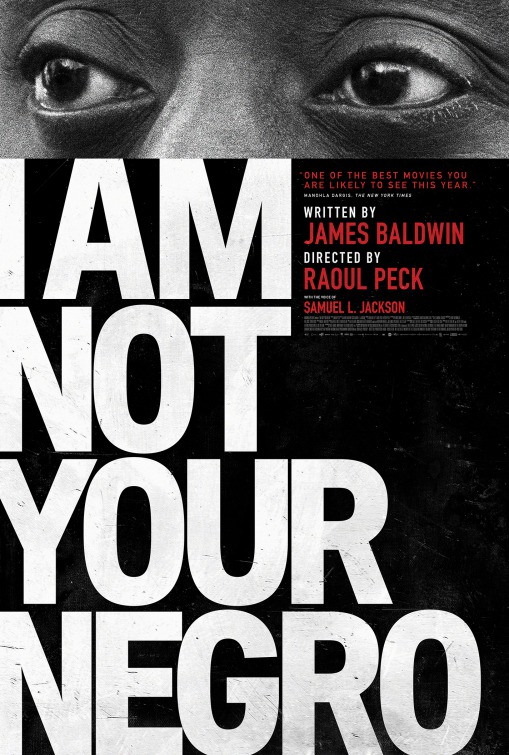

Baldwin’s 30-page manuscript, “Remember This House,” left unfinished on his desk upon his death in 1987, receives its coda in Raoul Peck’s tense yet brilliant 90-minute documentary, stitching together prescient decades-old lessons to the modern day.

In 1968, the year of Martin Luther King Jr.’s murder, talk show host Dick Cavett asks Baldwin, to the delight of his white audience, why “Negroes” in the country are not more satisfied with their ostensibly improving position in society — a similar platitude repeated today.

A white professor of philosophy on the show attacks identity politics, asserting that he has more in common with a black scholar than a white man against scholarship.

“Why must we always concentrate on color when there are other ways of connecting men?” he asks.

This film certainly attempts to answer that question, but it also asks why white America raises that question in the first place.

Peck explores the concept of race through American history using Baldwin’s words interlaced with a gamut of historical and modern images. Alexandra Strauss, the editor of the movie, realizes the power of the documentary through the style in which she presents it — a nonlinear, starkly contrasted and cleverly edited rumination on African American identity contrasted with white America’s conception of, and effect on, that identity.

A voice-over narration, provided by Samuel L. Jackson, is pulled entirely from Baldwin’s letters and books. Montage-based cinematography weaves his prophetic words with universally recognizable pictures, layering Baldwin’s meditative voice with historical images like Malcolm X’s lifeless body to contemporary scenes of protests in Ferguson, pointing out how far the world still has to progress in race relations.

But the documentary is not just a rebirth of Baldwin’s works to suit a present day point-of-view. It rekindles their importance and purposes their meaning.

“Remember This House” was partially based on the deaths of three civil rights activists: Medgar Evans, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. Throughout their successive murders, the audience feels the mixture of terror and frustration Baldwin expressed as “social danger” in his writing. That very same “social danger” that minorities feel and have felt in the United States becomes all too real when successive riots in April 1968 following MLK’s murder are juxtaposed with the 2015 unrest in Baltimore after Freddie Gray’s murder.

Even when there is hope, there is not. Bobby Kennedy presciently predicting a black president forty years from 1963 is repudiated by Baldwin’s reflection on the malicious arrogance of political discourse surrounding “the Negro.” Baldwin and Peck understand the threads of history that enable similar discourse surrounding African Americans — the inclination of whites to sanitize themselves of complicity, the dehumanization of blacks under disenfranchisement, the tension between an inability to comprehend privilege and the birthright to retain it.

Perhaps the most cynically rewarding — and the most haunting — aspect of the movie is the ability of an author who has been dead for thirty years to so accurately predict the capricious development of nebulously understood race relations in the United States. There are few essayists who write with the consciousness Baldwin does, which underscores and powers the command of his self-taught, street-learned excellence.

But most tellingly, Baldwin asserts, “I can’t be a pessimist because I am alive. So I am forced to be an optimist.”

Of course there is a solution. If not a one-part answer, then an answer found within the chaotically stitched together filaments of “I Am Not Your Negro.”

But if there is a broad explanation, Baldwin clarifies, “it is entirely up to the American people whether or not they are going to face and deal with and embrace the stranger they have maligned so long.”

That stranger they have maligned is not just African Americans, but according to Baldwin, themselves as well. That they themselves have convinced each other that racism is a relic of the past is exactly the same societal paradigm they benefit from. This conception becomes especially important in Baldwin’s final question in the documentary: Why was there a need for white America to create blacks as second-class citizens, to have them as objects of hate?

Baldwin believes that the necessity of asking the question is imperative to the survival of a multiracial society.

Peck perfectly combines that communal exhortation with the clarity of a conscious racial commentary. If there were required watching in this day and age, “I Am Not Your Negro” would be at the top of the list.