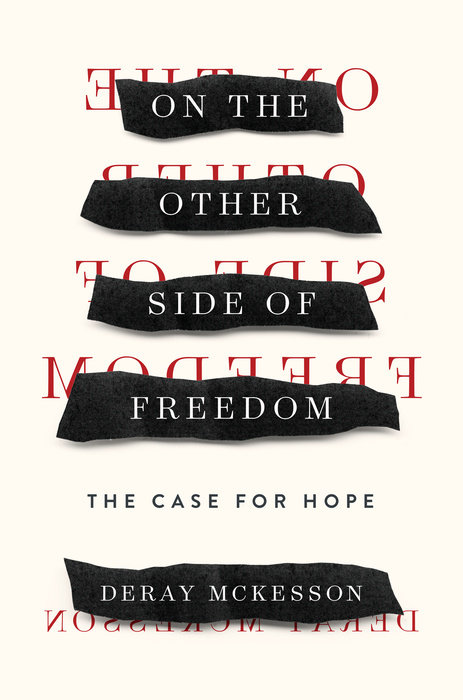

In his book, “On The Other Side of Freedom,” Black Lives Matter activist Deray McKesson compiles a compelling collection of experiences from the 2014 protests in Ferguson, Missouri that impart a lasting knowledge of the racial challenges our society faces, and our role in creating hope through community efforts.

Although the author scatters the concept of hope throughout the book, he introduces the necessity for such a powerful weapon in the first chapter. McKesson draws a clear line between faith and belief, explaining that hope is not a mystical feeling or emotion living within us, but rather a belief that is fueled by hard work toward a personal or public cause. Instead of relying on luck, he makes it clear that hope should be a strategic vision powered by a working attitude and specifies that the hope of black people relies on creativity and culture. Through the discussion of music, history and the power of community, he captures the identity that keeps the black population a people of culturally-driven aspirers and contributors to society.

McKesson goes on to address the fact that some may not view black people’s grievances as deserving of sympathy by introducing the earn/deserve paradigm. He explains it by seeing the world as a community that decides who is worthy of power. Those who have earned necessities such as housing, healthcare and education believe they’re entitled to the privileges they’ve been given. McKesson bluntly states that this inequity has led to a sense of superiority between different races. Using the police force as an example of those who believe they are above the law, he shows that the imbalance of power is not only racial, but also institutional.

The author supports his arguments about power imbalances through statistics, including the disturbing fact that black people are three times more likely to be killed by police than their white counterparts. Through his “Mapping Police Violence” database, McKesson creates a way to track police killings nationwide. The most jaw-dropping revelation was the fact that the rules of police departments vary heavily when it comes to the use of firearms. While some departments in California mandate gun restrictions, the other half of the country might allow for their policemen to shoot first and ask questions later at the slightest feeling of attack. McKesson goes on to identify laws and regulations that protect officers who have committed murder but claimed self-defense. Despite the claims of brutal inequality toward one class of citizens, he remains surprisingly hopeful, leading readers into his discussion about the power of technology-driven protest.

The author relies on technology for his widely-known and successful protests, especially with the Black Lives Matter movement. Comparing Twitter to a friend who is always awake, McKesson develops a relationship with social media that allows him to amplify his message, turning small phrases into powerful movements.

Though there are moments when McKesson is repetitive in his statements about hope and faith, “On The Other Side of Freedom” provides an engaging and compelling argument that acknowledges the racial inequality embedded in our system, yet remains hopeful for a society based on individual choices instead of systemic conformities.