A month ago, the Women’s March on Washington amassed over one million marchers in D.C. and over five million protestors worldwide.

In the event’s aftermath, feminist students and professors on campus are left figuring out how to take that energy and apply it to activism moving forward.

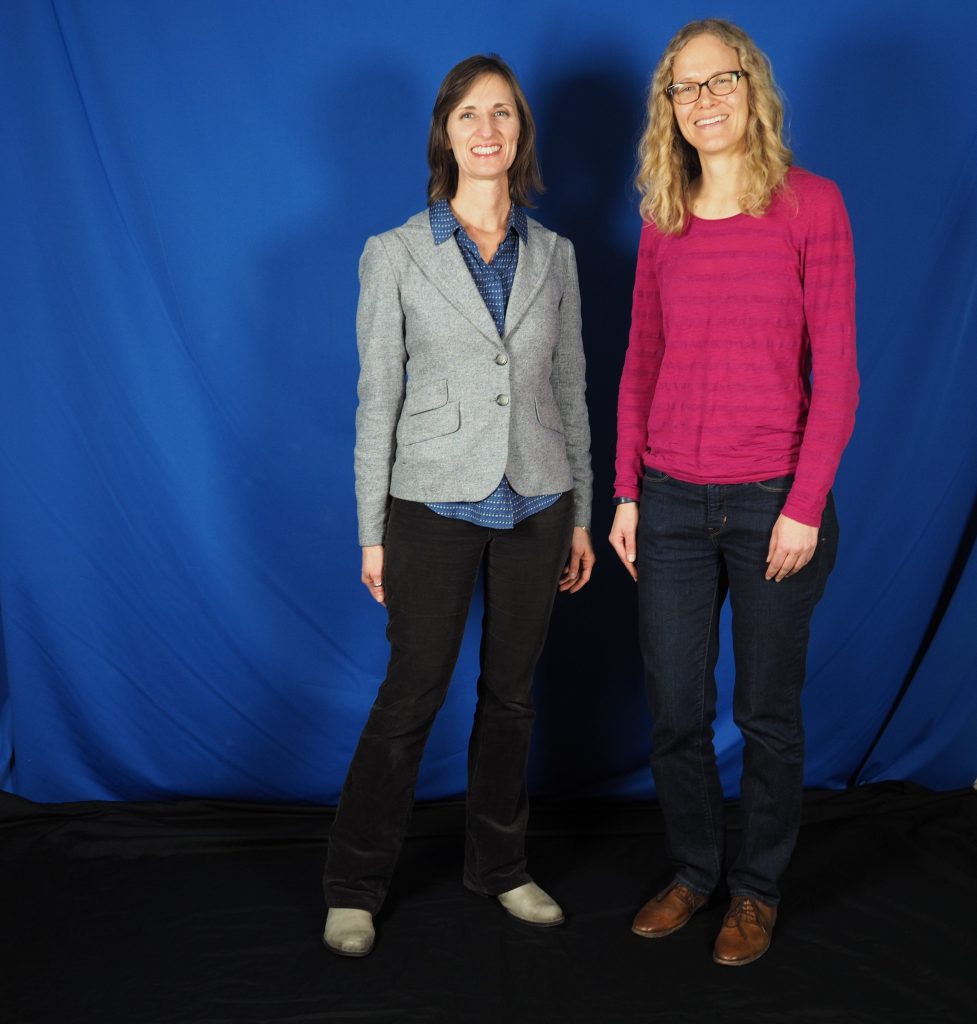

Annelise Heinz, an assistant professor of history in the School of Arts and Humanities, travelled with Assistant Professor of Film and Aesthetic Studies Shilyh Warren to D.C. to attend the march.

“For my own work as a historian, being there was really powerful and interesting because it was, I think, in many ways, this culmination of a long history of women’s activism and also significant change and evolution over time,” Heinz said.

So how does the march fit into the historical path feminism has taken over time? Heinz argued the fact that the march originated on Facebook is indicative of how feminism and activism has developed to fit the current cultural climate.

“This has happened many, many times before,” she said. “Mass events happening in a messy way with an individual spark, in this case, in our own historical moment, over social media. And having missteps.”

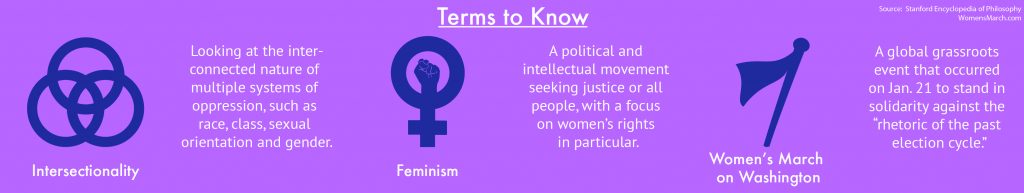

A common conflict news organizations, such as The New York Times and NPR, have addressed is whether the Women’s March — both on Washington and around the world — was intersectional enough. Intersectionality is the interconnected nature of multiple systems of oppression, such as race, class and gender.

“(There is a) difference between saying: ‘Race is a problem because feminism is a white women’s movement and white women don’t know what to do with race,’ versus, ‘Race is a point of conflict in feminism because feminism is an extremely diverse movement, and so race is going to be there and is going to be a point of conflict,’” Heinz said.

That point of conflict, the professors said, belongs within feminism.

“This is a process of ongoing growth,” Heinz said. “Of course it’s not enough. Let’s keep going.”

Further, Heinz said, criticizing the leadership of the march as lacking diversity is disrespectful, because a majority of the leadership was women of color.

“Part of my concern with having a conversation that frames feminism in the past and the women’s march today as a white women’s movement is that it further erases the real, essential centrality of women of color to these struggles of social justice from the beginning,” she said.

That erasure, she went on, fits right in to the historical path of feminism.

Heinz and Warren both saw the march as a training ground for people interested in activism. Heinz said she believes, in the future, the women’s march will be thought of as a moment of mass education.

“Having the march explicitly organized around ideas of solidarity and intersectionality sparked conversations for people who’d never had these conversations before,” Heinz said.

Going forward, Heinz believes the Women’s March is the beginning of a new structuring of the focus of feminist activism.

“If feminism becomes a mainstream organizing way of talking about intersectional issues of social justice, I think that that will help larger causes of social justice and help feminism,” she said.

Adam Richards, an electrical engineering senior and a member of Rainbow Guard, attended the DFW Women’s March. The major conflict Richards noticed was the strain caused by transgender exclusivity.

“Those were some of the tensions that I saw on display,” he said. “This kind of overarching, one size fits all feminism. The needs of people are very different. The biggest thing to me was just kind of the body parts language.”

For Richards, in the future it’s important for feminism to try to “coach” the language of reproductive health in more gender-neutral terms.

“It’s so important that this language is inclusive,” Richards said. “If you’re not representing everyone, you’re representing no one.”

The Intersectional Feminist Alliance at UTD attended the Dallas iteration of the march. Stevie Cornett, an IFA member and psychology senior, said the event marked an important opportunity for those upset with the result of the election to constructively protest.

“Change doesn’t come from us being in our own homes ranting on Facebook to people who believe the exact same thing as us” she said. “Change comes from honest, face-to-face dialogue, which is so lacking.”

April Harrison-Bader, a political science junior and IFA member, said an important aspect for feminists to improve on is allowing people from different groups to advocate for themselves.

“There is still a lot of improvement that can be made, but I think that this was a good first step,” she said. “But now I’m really kind of excited to see how we start to include minority groups.”

In the next month or so, the IFA will use the energy from the women’s marches to begin advocating for the different groups on campus.

“We bring in people from other organizations that we should be advocating for,” Bader-Harrison said. “To at least learn about the struggles they endure and what they think will actually help them.”

Despite the different ways for activists to go forward after the march, Warren stressed the importance of recognizing the Women’s March on Washington as more than one isolated event.

“Let’s not make the mistake of calling this one thing that people either belong in or out of,” Warren said. “Let’s remember that what we have here is a moment of activation or a catalyzed political moment where people who care about things deeply suddenly realize they’re not alone.”

Leave a Reply