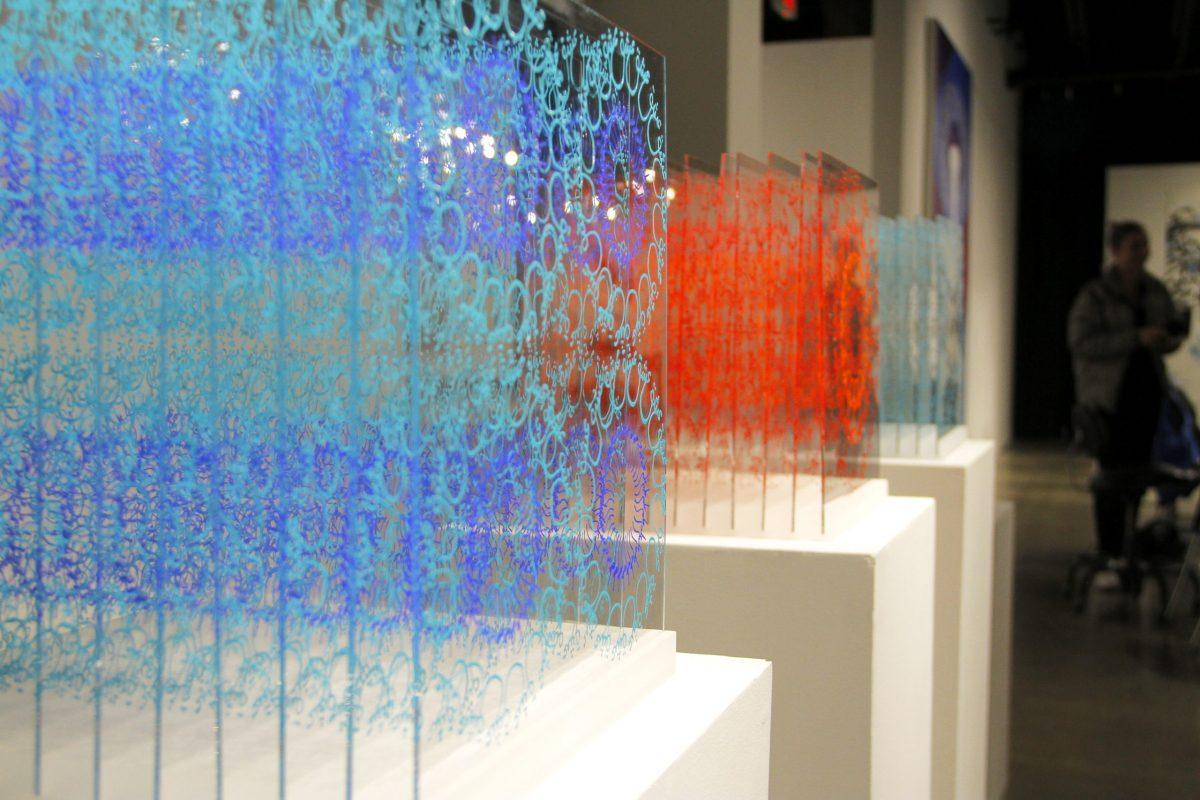

SP/N gallery's contemporary exhibition, Zarafa Unfolding, is running from Jan. 14 to Feb 15. Photo by Roshan Khichi | Mercury Staff

Middle Eastern, South Asian artists tell their stories through art works, installations

In the late 1820s, the Ottoman viceroy of Egypt gifted the

king of France a giraffe from Sudan. The charming animal, which was new to the

Parisians, inspired giraffe-themed wallpaper, spotted fabric and even

horn-shaped hairstyles among the French. The giraffe lived for 18 years in

Paris, attempting to adapt to a new land – and a new culture. She is now known

as Zarafa, a word in Arabic that means “charming” or “beautiful” and is a

phonetic variant of the word for giraffe, zerafa.

“Zarafa Unfolding,” an art exhibition at the SP/N Gallery

that runs from Jan. 14 to Feb. 15, holds true to its name: it is a collection

of stories from artists who have adapted to a new land, a home away from home.

In one piece, delicate calligraphy adorns transparent panels, with the word

“love” in Arabic, repeatedly drawn over and over. The artworks, which are

primarily crafted by Middle Eastern and South Asian artists, are soulful and

expressive, depicting both the brutality and beauty of adapting to a new

homeland, often due to war.

Greg Metz, an arts and humanities professor at UTD and the

curator of “Zarafa Unfolding,” said that the stories in the exhibition are from

artists who have successfully adapted and lent their contribution to the

cultural fabric of Dallas.

“One of them is from San Francisco, one of them is from

Virginia, one of them is in Maryland, one of them is in New York, but from

Istanbul,” Metz said. “I wanted to demonstrate that there isn’t a signature

style that says Middle East, South Asian art. There’s an Islamic kind of

referencing in some of the work. There is a lot of reference to contemporary, a

contemporizing of calligraphy.”

A soulful recording of a man reciting adhan, the Islamic

call to prayer, rings out softly in the background of the entire exhibit. The

voice is melodious and reminiscent. Perhaps that is like the exhibit itself, a

reminder of what loveliness resides in our diverse universe – and how swiftly

it can be stripped away.

One hanging installation created by Fahimeh Vahdat, a

Bahá’Wí from Persia who immigrated to the U.S., features circular panels

dangling from the ceiling, with women’s faces printed on many of them. In one rose pink illustration, magenta

smudges partially obscure a woman’s somber face, while in another piece, gray

lettering is drawn repeatedly over another woman’s face.

“(Vahdat) … has gone on to really make a name for herself,

and all of her work is about injustice and domestic violence mostly in her

country that she’s come from, but also how some of that is held over and demonstrated

here,” Metz said. “That hanging piece has portraits of women who have been

disfigured by having acid thrown on their faces. So when you look at that and

you see the drops and things that are drawn into those prints or etched into

those prints, that’s the acid disfiguration of an identity trying to be

erased.”

A heartbreaking video installation depicts a man named Abdul

Ameer Alwan painting soft pink landscapes in front of the camera and watching

his daughter play in a park, hoping that she doesn’t forget Iraq.

“All my friends and I are hoping to return to Iraq sooner,”

he said in the video., “Today before tomorrow.”

The video evokes a solemnity that is peaceful with a touch

of sorrow. One cannot forget that this man was displaced from his home due to a

violent, bloody war. Metz said that Alwan never truly adapted but passed away

of, more or less, a broken heart. His art, so celebrated in Iraq, was not

considered with the same interest in America.

“He’s someone who came over as a mid-career artist who was

well-respected in Baghdad. After the war started in 2003 as we invaded Iraq, he

was exiled to Jordan and then he lived in Jordan for four years until they

closed the galleries down there,” Metz said. “When he got here in Dallas, he

experienced a tornado for the first time. So he compared what he went through

and what his family went through with the invasion of Iraq as a tornado, you

know, their tornado or their version of the tornado.”

here’s a little bit of everything in the show, Metz said, but

there’s not a signature style or a stereotypical way of looking at the art

created by the artists in this exhibition.

“The story trying to be told by this exhibition is how

creatives adapt to a new homeland, how they creatively express themselves in a

different surrounding reflective of both their culture, their historic

descendancy, but also trying to adapt to a very contemporary world and trying

to compete on the level of a larger contemporary art world,” he said.

“‘Unfolding’ is the telling of that story.”