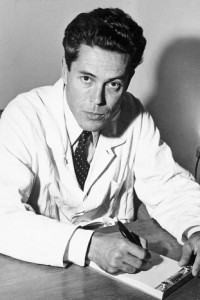

Jacques Monod was a scientist by day and an activist by night. He lived during World War II and worked to accomplish more than his scientific ambitions, fighting for freedom for his country and family.

Scientist, author and educator Sean B. Carroll wrote about Monod and the philosopher, Albert Camus, in his latest novel, “Brave Genius: A Scientist, a Philosopher, and Their Daring Adventures from the French Resistance to the Nobel Prize.”

On Jan. 14, Carroll presented “Brave Genius” at The Dallas Museum of Art as the first lecture of the lecture series Ad Astra, curated by associate professor of art history, Charissa Terranova.

“The best way I can summarize the theme of tonight’s talk is with this little pearl from Henry van Dyke: ‘Genius is talent set on fire by courage,’” Carroll said.

Ad Astra, meaning “to the stars,” was created for The Edith O’Donnell Institute of Art History.

“(Ad Astra) looks forward to a movement into an age where art and science explore new areas through computation,” Terranova said.

Carroll’s book takes place in Paris during World War II through the postwar period to the student and worker riots of May 1968.

In addition to telling the history of this time period, “Brave Genius” sheds light on the shared mode of focus: Monod, a founding figure of microbiology, and Camus, an existential philosopher. It is a story of big ideas, Carroll said.

Monod was a researcher at the Sorbonne in Paris, studying the genetic control of bacteria that eventually led him to win a Nobel Prize.

But as German control intensified during World War II, Monod sent his Jewish wife and children outside of the capital for their safety and joined the most militant resistant group.

In 1970, he authored the book, “Chance and Necessity,” which focused on the processes of evolution that demonstrated that life is only the result of chance.

“This book really could’ve been his autobiography because chance played a role in his personal life,” Carroll said. “If you had met Monod in the late 1930s, you would’ve seen no sign of the greatness that was to come.”

Camus, on the other hand, came to Paris from Algeria in 1940. Though a novice writer, by 1944, he became the editor of the resistance newspaper Combat. His anonymous editorials urged Frenchmen to take action against the German occupiers.

“These two men both saw the darkest days of World War II and did not shatter their optimism,” Carroll said. “They saw the threat coming from Stalin and the Soviet Union, but they stood up when it cost them a lot, and they held these thoughts to the ends of their lives.”

In the beginning, while Camus made a difference through his published writings, Monod took a more hands-on approach.

Using the alias “Malivert” and working with student Geneviève Noufflard, Monod went on to become a high-ranking staff officer of the national resistance organization, the French Forces of the Interior.

As Monod’s liaison, Noufflard passed along messages to and gathered intelligence reports from other resistance members in hopes of assisting the Allied bombing effort and sabotaging Axis operations.

“As much as he knew that science was the engine behind technology that infected all of our lives, he felt that the most important results of science were to change our relationship with the universe and the way we see ourselves in the universe,” Carroll said.

After investing six years of his life into the war, Monod felt, with desperate urgency, that it was time to turn back to science. He started to look for people to work with in his lab.

“He said to one of them, ‘I don’t care if you don’t have any experience,’” Carroll said. “‘That’s perfect background as I’m in search of the secrets of life.’”

While Monod continued his research on the science of genetics and chance, Trofim Lysenko, a Soviet biologist and agronomist whose crop improvement research gained the support of Joseph Stalin, rejected genetics as a science.

In fact, he wanted a revolution to throw out Western science and completely abandon the science of chance, which he referred to as genetics.

Monod was stunned, Carroll said, and publicly criticized of not only Lysenko, but also the entire Soviet scientific establishment, despite how well the communist party was doing in France.

His first op-ed appeared on the first page of Combat. The headline read, “Lysenko’s victory has no scientific character whatsoever.”

This single op-ed was the reason Camus and Monod met because, at this moment, these same thoughts were running through Camus’ mind.

In 1948, the two men were finally introduced and hit it off almost instantly.

The men met often in cafés in Paris to dine and exchange ideas. At this time, Camus was working on his book, “L’Homme révolté,” meaning “the rebel.”

Like Monod, Camus took a public anti-Soviet stance and even included some of Monod’s scientific research in his book. When it was published in 1951, it triggered a major separation from Camus’ affiliates of previous years, Carroll said.

“He was taken by surprise by how strongly his closest friends reacted to this book,” Carroll said. “But he found this new friend in Monod, and it became clear they were both seeing the world in the same way.”

The two men’s common perspectives and similar cause formed the irreversible friendship that Carroll’s book centers around.

Carroll said he hopes through this compilation of art and science, art will finally lead science to find its valued place in American culture with the ability to visualize, dramatize and tell stories.

Like Carroll, freshman Rachel Zhang also supports the transition into an art and science world of expertise.

“For so long, people have classified art as something completely irrelevant to technology or science,” Zhang said. “Dr. Carroll’s book presents to us, through the scope of history, all the greatness that can take place if the two fields are compiled. We might find out that there’s a lot of unexplored possibilities out there that can make a huge difference in our daily lives and change our perception of what art can be.”

Carroll said he believes if he were in Monod’s place, he would have chosen to fight the Nazis. However, he also realizes that there is no way of knowing for sure how one would act in such a high-stakes situation.

Perhaps one has to lose one’s freedom and face the abyss to truly appreciate liberty and the opportunity to create, he said. But for now, Carroll is focusing his attention on the people who stepped up during unfavorable situations.

“These people had more courage in their finger than I’ll ever have in a lifetime,” he said. “We need true stories about people who rose to the occasion in all times, from all cultures, to remind us of our better selves.”